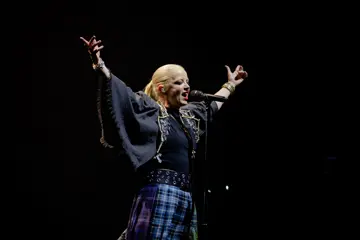

COURTNEY BARNETT

On how she found out she was nominated for two Carlton Dry Independent Music Awards this year, Courtney Barnett reveals, “I think [how] you find everything else out – on social media.” Was it a tweet? “Yeah, I think maybe someone like you guys [TheMusic],” she laughs. When asked what the last thing was that she won, Barnett chuckles, “I don't think anything. I came runner-up in a colouring-in competition in primary school… And I only know that because when I was at the APRA Awards, I was gonna say that in my speech if I won. But I didn't win.” It was a Lego colouring-in competition, so the prize was “a pack of Legos”, but Barnett admits, “I've always felt guilty about it 'cause my dad did most of the colouring.”

After financing the manufacturing costs of first EP (I've Got A Friend Called Emily Ferris) with “all [her] own money”, Barnett was “lucky enough to get a grant from Arts Victoria” for follow-up EP, How To Carve A Carrot Into A Rose. When asked about the endless paperwork one needs to fill out when applying for a grant, Barnett confesses, “My manager wrote the majority of the grant. I tried to write grants over the last few years when I didn't have him and I just failed.” When Barnett was 21, she was fortunate enough to meet her manager, Nick O'Byrne, through The Push's FReeZA Mentoring Program “for people under 25 or something”. “I was flailing around for years, not getting very far,” she reflects. Increased motivation and success followed once she paired up with O'Byrne: “It's just being put in touch with people and, you know, socialising with those like-minded business people.

“We work together on every single thing that comes up. So it's really good having that kind of support… Just to bounce ideas off each other, it really helps, as opposed to just being in complete charge and – you know how you can go a bit crazy by yourself?”

Barnett's History Eraser single is also available as part of a split-7” (with Jen Cloher's Mount Beauty). Barnett plays in Cloher's backing band and, before they embarked on a double headline tour earlier this year, the pair decided, “We need something to take with us,” because they were both in between releases.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Although technically Barnett defines being an independent artists as “not being part of a major”, she adds, “but to me it just means being in control of my own career, or my own music.”

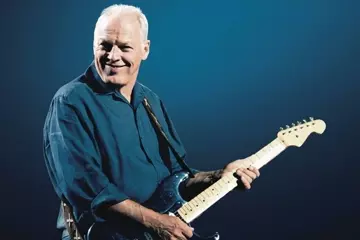

BIG SCARY

On how Big Scary financed their Best Independent Album-nominated album Not Art, drummer/vocalist Jo Syme shares, “All our finances have come… it's a little bit of touring, a little bit of album sales from Vacation and I guess we've got a really great publisher [Gaga Music]. I think for independent artists, the publishing is really the mother lode 'cause it's really changed, people's income stream. But if you can sync your songs on some TV or movies – the big payers are on adverts and I think we had a bit of that [money] stored away.”

This will be the first time the duo grace the awards stage. “I think it'll be really fun,” Symes enthuses. “I get along with everyone at AIR [Australian Independent Record Labels Association], and all the other bands playing, so I just said to them, 'Can we please not be last?' 'Cause I still wanna have a drink [laughs].”

Syme and her Big Scary musical partner in crime, Tom Iansek, recently collaborated with Sydney producer Jonti. “People would say they wanna collaborate all the time and I'm always like, 'I think it would be awkward',” Syme reflects, on previously being skeptical about collaborating with other musicians. The Jonti experience made her change her tune, however: “That was so fun. He came in and we just started playing… I think 'cause it was so easy it made me much more open to wanting to work with people.

A unique situation has occurred this year in that the Best Independent Artist nominees are exactly the same as those for Best Independent Album. So much for the Death Of The Album, huh? Syme raises a good point when discussing the genre divide: “Dance bands are really forging the single release and that's working for more electronic dance music, but I think you need the album to promote the tour and you need the tour to promote the album, you know?” As such, it's become increasingly important for artists to be able to back it up live in order to balance the books. “It shouldn't be that the artist has to be good live if they're just good at making songs,” Syme laments. “Sometimes [it seems] they have to be to make a living. I find that unfair.

“[Even] if festivals and shows have kinda taken a bit more precedence over the money coming in from albums, I think people are still enjoying album tracks. Like, we get comments from people on songs that aren't singles, so that's really cool.”

SETH SENTRY

If you have a visual of indie artists packing their own EPs into boxes and driving around to record stores, begging for some shelf space and hoping to leave ten copies on consignment, this fits Seth Sentry (if you rewind four years). To distribute his The Waiter Minute EP, Sentry says, “I'd go around to shops and – because I wasn't very good at it, 'cause I'm not a very good businessman – I'd forget what shops I'd go to, I wouldn't write down how many [copies] I left. I only recently went into a shop in Brunswick and I was gonna buy a hat and, when I was in there, I was like, 'Fuck, this shop seems familiar!' And then I remembered I'd given the guy ten of my EPs to sell, like, four years ago and never came back in to see whether he'd sold 'em or anything. And when I asked him, he was like, 'Ah, I can't remember'… and I couldn't remember, so I was like, 'Oh well, that's why I shouldn't do everything myself'.”

Nowadays, Sentry operates as part of a trusted team. It all began when he was approached by his now-manager, Rowan Robinson, after “a random show in WA” in “late 2008, maybe early 2009”. At the time, Sentry was working in hospitality. “To be honest it wasn't a particularly good show, either. There was just something that he liked about the music.”

For his debut album This Was Tomorrow, Sentry wanted to create an album that people would want to purchase in its physical form and digest in full. In recruiting the same artist who designed his EP cover for the album artwork, Sentry created an incentive for fans: “If you fold out my EP and my album, the artwork makes one long panorama if you join them up together.” He builds a strong case for CD buyers, recalling excitedly: “I remember my dad playing me Dangerous by Michael Jackson – that was the first album that I ever bought – and it was a two-hour drive back from the record shop, which was in the city. I spent the whole two hours just reading that shit front to back, like, reading every liner note and looking at the artwork. I think that's starting to get lost these days when people just download stuff off the Internet and, you know, listen to a couple of the singles and maybe a couple of the album tracks and then [they're] kind of done and move onto the next thing.”

Sentry won the Channel [V] Oz Artist Of The Year Award in 2012 and still sounds shocked. “I don't even know how I won it, but I won it. “There was obviously a lot of exposure and stuff after that, and that led to a lot of cool things,” he reflects, “and I guess I felt like maybe people took me a bit more seriously in the music scene or whatever.” More than 1.66 million votes were tallied Australia-wide before Sentry was presented with this “cool trophy”. The fact that the rapper enjoys social networking would certainly have helped. “I really dig [social networking], it's never really seemed like a hassle or something that I had to do or anything.”

Even though Sentry is no longer a one-man operation (“we've got a great publicist and we've got a great booking agent that we really trust”), he still approaches music as a hobby: “It still doesn't feel like a real job to me and I'd like to maintain that attitude as long as possible.”

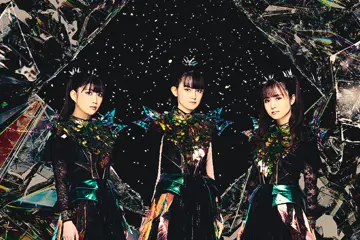

FLUME

Reflecting back on the recording of his self-titled debut album, Flume (aka Harley Streten), shares; “There was nothing fancy about it, really, and that's the beauty of it I think: You really don't need money at all to write music these days: Good music doesn't require money. I think that's what a lot of artists who get signed to major labels don't realise.”

Streten's the first to admit that his story would be markedly different had he found himself in the centre of a major-label bidding war. “If a major label had stumbled across me I would've just signed some huge contract with them and, um, I would be nowhere near where I am right now. And I think there's a lot of luck involved with that,” he muses. “I think [advances] put a lot of pressure on the artists once they've spent some of the money and they realise, like, 'Man I've gotta make this back!' I wasn't really offered money and stuff and I think that worked in my advantage... It was a really healthy environment to write in.”

Streten remembers his first meeting with Future Classic well. “It would have been a year and a half ago or something like that and I came home from the meeting, and the last thing that they said to me was – essentially as I was walking out the door – they were just like, 'So what we want you to do is basically make your own genre,' like, as a joke.

“It was about the attitude of the label. It just ticked all the boxes in the sense that, first of all, it wasn't a money thing – like, any major label, you know, they need to make money really badly and unfortunately a lot of the time that's what it's focused around. And [Future Classic] just wanted to put out new interesting stuff that they liked and it seemed really legit.”

Don't worry; Streten is acutely aware that Future Classic uses Warner's back-end “to do some of the things like distribute the record, which a company like Future Classic could never do”. “I don't wanna be badmouthing majors or anything,” he stresses, “they have their pros, they have their cons. I feel very fortunate to not be on one… I think it's just about having a good balance and, depending on the kind of artist you wanna be depends on where you should be. I mean, if you're gonna be a pop star, I definitely would recommend going with a major over an indie. So it really just depends on your situation.”

Although Streten's “never been one to wanna be in the spotlight”, he's getting used to it. “At first, like, doing interviews and going and playing in front of people every weekend, I was very uncomfortable, but after time I knew that would fade and it would be easier and I would benefit from that. So I just persevered and didn't turn down any opportunities and always kinda put myself out there as much as possible… It definitely forces you to grow up quickly and I got dropped in the deep end pretty hard, but I feel like now I'm way more on top of it all and I'm pretty comfortable with everything.”