Late last month, news broke of a deal between generative artificial intelligence music creation platform Suno and one of the world's largest entertainment companies, Warner Music Group.

Equally described as both a "new chapter in music creation" and a "groundbreaking partnership" by those involved, what the news boiled down to was the fact that a generative AI company had officially partnered with a music company – two forces that have traditionally been seen as being in opposition in this current era.

But what does a partnership like this mean? Well, firstly, let's take a look at what Suno is.

Officially launching in December 2023, Suno will this week celebrate its second birthday, having been founded as a way for anyone to use artificial intelligence to create pop songs.

And by 'anyone,' we mean anyone. If you don't have any musical skills, that's not a barrier to entry – simply add in a few text prompts and before you know it, you've got a song that effectively has the potential to top the charts.

@sunomusic you are now the instrument.

♬ original sound - Suno - Suno

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

It's worth noting, of course, that Suno isn't the only platform allowing users to turn text prompts into tunes. There's Udio, AIVA, Soundraw, Beatoven.ai, and others, but Suno is the one you're likely the most familiar with – if you're familiar with any of them yet.

The controversy that the likes of Suno has been attracting makes sense. After all, we live in an age in which AI technology is becoming increasingly prevalent, and in many cases, is being thrust upon us without consent.

The music world has been very vocal (no pun intended) about their opposition to AI in the industry. After all, music is human artistic expression, and when you remove the human from the equation, you're left with 'art' crafted without soul.

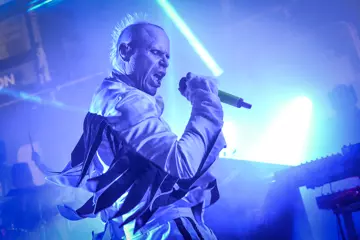

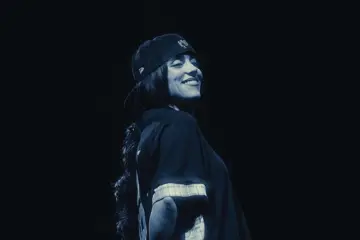

In 2024, more than 200 artists – including Billie Eilish, Pearl Jam, Chappell Roan, and the estates of Bob Marley and Frank Sinatra – signed an open letter against big tech using AI and the rising practice of training models on copyrighted works, and since then, things have only snowballed.

In July, a band named The Velvet Sundown went viral, attracting over half a million listeners despite being being AI; and then in October, we saw the other side of the equation, with APRA AMCOS and the rest of the Aussie music industry celebrating after the Federal Government ruled out a proposed text-and-data-mining exception in the Copyright Act.

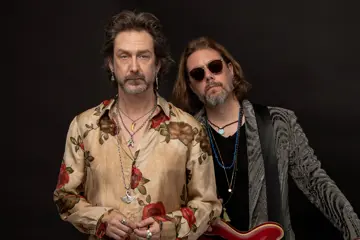

The hits have kept coming though. We've seen AI band Bleeding Verse overtake Welsh rockers Holding Absence in terms of monthly listeners despite citing the real group as an influence, and we've most recently seen King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard's high-profile exit from Spotify being punctuated by an alleged gen AI act dubbed King Lizard Wizard aping their music style on the platform.

There have been some good news stories when it comes to AI usage in music, however. In November 2023, we saw The Beatles release the single Now And Then, with director Peter Jackson utilising AI technology to extract John Lennon's vocals from a 1977 demo in order to complete the track – almost 43 years after the singer had passed. The track topped the charts and even won a Grammy.

To come back to Suno, we've also seen UK act HAVEN. have their viral hit I Run removed from streaming platforms (and the pointy end of the UK charts) after allegations arose that the track's vocals were generated using Suno, with some claiming they were actually an AI deepfake of Jorja Smith. A new version of the track was later released, this time featuring real vocals from Kaitlin Aragon.

We've seen the very topic of computer-generated music become something that is loathed by the artistic community, yet become increasingly accepted by the general public. We've also seen the vast majority of stories relating to music and AI being met with overwhelming amounts of disdain.

In fact, this very partnership between Suno and Warner began with controversy in the air. Back in June 2024, were among a number of majors – including Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, Atlantic Records Group, Capitol Records, and others – who launched legal action against Suno and fellow gen AI platform Udio, alleging copyright infringement.

In October 2025, Universal stated they had reached a settlement and licensing agreement with Udio, and the following month, we received the news that as part of their own settlement, Warner had struck a partnership with Suno.

So, what exactly does this mean for the wider industry?

Well, to put it simply, at the current time, a greater amount of clarity is needed to specifically say who the deal is good for and who will likely benefit the most.

In their statement last month, Warner explained that this new deal will open "new frontiers in music creation, interaction, and discovery, while both compensating and protecting artists, songwriters, and the wider creative community."

In Suno's statement, they explained how this partnership meant the two companies would be able to "create a paradigm shift in how music is made, consumed, experienced and shared to delight music fans around the world."

On one hand, these statements are dripping in standard press release positivity, suggesting a brighter future in which musicians will be compensated and the possibilities surrounding music creation will be taken up a notch.

However, while Suno was previously a platform that allowed anyone to create their own music, it wasn't one largely being embraced by the majors.

While some cynical consumers would have felt confident in writing off its existence given that it might be a tool used only by bedroom producers, what does it now mean that the majors have access – and motivation – to use the platform?

Given that Harvey Mason Jr. – the boss of The Recording Academy and the Grammys – recently explained that he had witnessed musicians of all levels utilising AI to aid in musical creation, and outlined that AI isn't necessarily a dealbreaker when it comes to Grammy nominations, where do we draw the line when AI music creation software is in partnership with one of the big three major labels?

This is, of course, an extremist (and certainly cynical) viewpoint to take. After all, Warner themselves have outlined that their main motivation for partnering with suno was to "shape models that expand revenue and deliver new fan experiences."

"AI becomes pro-artist when it adheres to our principles," explained Warner Music Group CEO, Robert Kyncl. "Committing to licensed models, reflecting the value of music on and off platform, and providing artists and songwriters with an opt-in for the use of their name, image, likeness, voice and compositions in new AI songs.”

This sort of artist-first protection is in line with a new raft of guidelines that have been implemented recently, most notably by the likes of Spotify.

In September, the streamer explained they had taken big steps in strengthening AI protections for artists and producers, including introducing a new impersonation policy, investing more resources into their content mismatch process, and working toward a new industry standard disclosure for music which features AI.

The Suno and Warner partnership also came with new announcements relating to how users would be able to embrace the Suno app for music creation in the future. Asserting that "our core experience remains focused on giving everyone access to powerful music creation," a few changes were outlined in their November statement.

A big one is the fact that for users to download their creations, a paid account will be a necessity. In theory, this would help reduce the amount of AI 'slop' out there, created by those simply experimenting on the app for a lark and uploading to platforms such as TikTok, where AI-generated music often spreads like wildfire.

The other big announcement – as Kyncl's statement alluded to – is the fact that Suno will now be able to utilise content from Warner artists who have opted in to allow their "names, images, likenesses, voices, and compositions to be used in new AI-generated music."

While this then allows new revenue streams to open up for these Warner artists, a more cynical mind could then ask if this means that as AI-generated content grows, and a push for legal avenues to be explored in its creation is enforced, could this simply result in a monopoly for Warner when it comes to AI music?

Currently, it's unclear if this opt-in system allows for Suno to train its gen AI model on Warner artists, but if it does, could this then mean that all music created by the platform will be harnessing a 'Warner sound'?

This last point is one of many questions that remain when it comes to what exactly a partnership such as this means.

Currently, the revenue distribution in this new landscape has not been outlined. It's unclear just how the revenues will flow back to the artists that models have been trained on, and likewise, there is yet to be an outline in how that revenue will be shared between the artists and the label.

Then, there is also the question of the artists that do indeed choose to opt out of this new partnership. In much the same way that artists are able to remove themselves from streaming if they wish, the ubiquitous nature of streaming platforms and the rising prevalence of AI raises the question of whether artists are actually being given a choice, or whether they're effectively closing off a vital revenue stream.

Lastly, given that Australia has expressly ruled out 'fair use' as an exception to copyright deals, what then happens if an artist whose music has already been utilised by AI models chooses to opt out of this partnership? Can the AI model 'forget' their musical contributions? Can they sue over unauthorised use? Or will this deal with Warner prevent such litigation?

The Music has reached out to both Suno and Warner Music Group with a number of questions, but at the time of publication, had not responded.

Admittedly, some of these questions may be answered in the coming weeks and months as Suno firms up the release of its new features and likely further outlines where things are going.

But in the interim, it appears as though the year is once again ending with a reminder that generative AI technology is continuing to evolve and that it's anyone's guess what the landscape will look like in another 12 months.