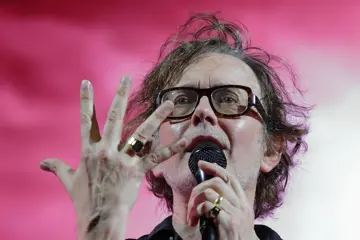

The Pogues

The PoguesWhen I was first introduced to Fairytale Of New York as a child, I was appalled. This was what my parents were calling their favourite Christmas song?

A song, delivered in a drunken growl, about spending Christmas Eve in the clanker and reminiscing on a doomed romantic partnership where both parties were calling each other slurs?

Surely, Christmas was supposed to be about presents and pudding and Bing Crosby. The adults, I decided, had officially gone insane.

It wasn’t just my parents who went crazy for The Pogues. In the UK, Fairytale Of New York is the most-played Christmas song of the 21st century. It is frequently cited as the greatest Christmas song of all time.

And though I couldn’t understand that at all when I was a child, I understand it now, because – unsurprisingly – it has become my favourite Christmas song too.

As I left childhood behind for adolescence, and then suddenly found my way in the midst of adulthood, I learned that Fairytale Of New York is by no means an outlier. Christmas music is often melancholy, if not downright tragic. Let’s peruse a brief list of Christmas classics.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Wham!’s Last Christmas – totally inescapable every December – is about a messy break-up. Tom Waits wrote from the perspective of a pregnant, lonely, poverty-stricken sex-worker on Christmas Card From A Hooker In Minneapolis.

Band-Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas? was written to raise money for the 1983–1985 famine in Ethiopia, and it remained at Number One on the UK Singles Chart for five weeks. (It sold a million copies in the first week of release, rendering it the fastest-selling single in UK chart history at the time.)

One of Joni Mitchell’s biggest hits, River, interpolates Jingle Bells but it is beset by feelings of loss, and all Mitchell wants is to be able to “skate away” from everything. John Lennon protested the Vietnam War with Happy Xmas (War Is Over), as did Stevie Wonder with Someday At Christmas.

Merle Haggard and The Strangers chronicle the struggles of working class families during the holiday season on If We Make It Through December. And it would be remiss not to mention Paul Kelly’s feat of composition, How To Make Gravy – a song which frequents the ARIA charts in December (and was recently voted #9 on triple j’s Hottest 100 Of Australian Songs), a song which, centring as it does on incarceration over the holidays, is achingly sad.

As recently as 2020, Julia Jacklin gave us a heartbreaking Christmas tune with Baby Jesus Is Nobody’s Baby Now.

One could argue that the inclination toward the pessimistic in Christmas music is a more modern phenomenon. But even more traditional numbers like Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas and I’ll Be Home For Christmas still ache with sentiments of separation, of being apart from family during the holiday season.

White Christmas, too, is not without its subtle melancholy. “I’m dreaming of a white Christmas, just like the ones I used to know,” is, to me, a lyric steeped in sadness, reminiscent of times past, times that can never be had again.

Christmas is a season that goes hand in hand with descriptors like “merry” and “jolly.” Why, then, is so much Christmas music so sad, and why does it resonate with all of us?

Much of this can be explained by the fact that much of the iconic Christmas cannon we know and love today was conceived of during World War II. White Christmas – the world’s best selling single according to the Guinness Book of World Records - was written by Irving Berlin for the musical film Holiday Inn in 1942, just after the United States officially declared their involvement in World War II.

(It is also worth noting that Berlin’s son tragically passed away of Sudden Infant Syndrome on Christmas Day in 1928, which perhaps fuelled the song’s tone of wistful longing.)

Bing Crosby’s I’ll Be Home For Christmas was recorded in 1943. The song was a hit amongst Americans, earning Crosby his fifth gold record. It became the most requested song at Christmas U.S.O. shows. (The BBC, however, banned broadcasting it, worrying that its melancholy nature would lower morale amongst soldiers.)

Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas was written in 1943 for the Judy Garland vehicle Meet Me In St. Louis.

Though in the film, the song centres on the protagonist’s father planning to leave home for a work promotion, the sentiment of course resonated with families separated by war: “Someday soon we all will be together/If the fates allow/Until then we'll have to muddle through somehow.” The year it was released, the single reached #27 on the Billboard charts.

Christmas music as we know it, then, is rooted in a tradition of separation and pain.

Christmas is a season that we understand, on some fundamental level, is complicated for many, if not all.

The belief that people are more likely to die by suicide during the holidays season is in actuality, a misconception, but the fact that this misconception persists – and even exists in the first place – speaks volumes. Even if it is a statistical falsehood, this pervasive belief gestures at the fact that, as a society, we associate Christmas, at least partially, with despair.

Perhaps Christmas reminds us of what we miss most. Christmas is founded on traditions – if not religious or cultural traditions, then family or personal traditions. But things always change, and Christmas brings these changes into harsh focus.

December reminds you that relatives who used to bring the roast spuds are no longer with us, the the partner you spent last Christmas introducing to your family is now being introduced to someone else’s family, that you used to believe in Father Christmas and now you don’t, and you never will, and therefore you will never be as young as you once were.

It is when happiness is mandated that it is sometimes harder to feel it. When fairy lights blink around you, when gorgeous displays are erected in your local shopping centre, when everyone is rigorously wrapping gifts, when everyone around you is full of cheer – or are, at least, presenting themselves as such – it is easy to become more aware of the fact that something is missing. It is easy, and only human, to feel at odds with such unabashed exhibitions of joy.

Or, as LCD Soundsystem puts it on one of my favourite (and most anguished) Christmas songs, “Christmas will break your heart… Christmas will crush your soul… Christmas will wreck your head… Christmas will shove you down… And Christmas will drown your love.” (James Murphy’s outlook is, admittedly, on the extreme side of the Christmas Blues Spectrum.)

There is a reason that what many consider to be the greatest Christmas film of all time ultimately centres on a man contemplating suicide. In It’s A Wonderful Life, George Bailey, played tear-jerkingly by James Stewart, stares into the dark waters of an icy, rushing river.

A banker who has misplaced 8,000 USD (the equivalent to $133,000 USD today), he is facing financial and social ruin. Told recently by the movie’s snide villain, Mr. Potter, that he is “worth more dead than alive,” George considers making the jump, ensuring that his wife and children are taken care of by his life insurance.

Christmas should be a time of prosperity, but it so rarely is. It is, in fact, a time of year that poses a massive financial burden.

One of the reasons that If We Make It Through December has been consistently covered – by Alan Jackson, Marty Robbins, and most recently by folk star Phoebe Bridgers – is because financial insecurity is a sentiment that resonates. And it is a reality that is not at all helped by the hyper-acceleration of late-stage capitalism. A modern-day Christmas goes hand in hand with rampant consumerism.

According to a study by Choosi in 2023, Australian parents spend a whopping average of $582 per child for gifts in the festive season. Across food, presents, and decorations, the average Australian family will spend $1.86k on Christmas. That is 74 hours of work at the national minimum wage. 8% of Australians (1.7 million) people left Christmas 2024 and went into the New Year in debt.

The crux of the matter is that the world doesn’t stop just because it’s Christmas. Global crises persist, as do personal crises, even when the Christmas tree is taken down from the attic. And it helps to have a sonic reminder that, even if it is the season to be jolly, it is normal to struggle to smile all throughout December.

Every year, I find myself coming back to Fairytale Of New York. Because it is sometimes reassuring to have your heart broken by a Christmas song.

This article discusses mental health issues and suicide. If you or someone you know is suffering from depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts or other mental-related illness, we implore you to get in contact with Beyondblue or Lifeline:

Beyondblue: 1300 224 636

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Suicide Call-Back Service: 1300 659 467

Beyondblue and Lifeline both offer online chat and counselling. Please check their respective websites for operational hours and additional details.