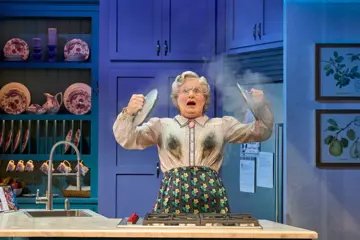

As every poorly coordinated disco shaker knows, some tracks are much harder to dance to than others. However, we would not perhaps expect the same to be true of the highly trained, physically adept dancers of the Australian Ballet. That is, until you factor the music of Igor Stravinsky.

Indeed, in the lead-up to our national company's 20:21 showcase of contemporary ballets even the principal artists are having more than their usual share of difficulties with the legendary Russian iconoclast's abstruse score for choreographer George Balanchine's modern classic Symphony In Three Movements.

"It's very energetic, very raw and visceral. It's kinda sexy too."

"Yeah, it's hard," admits Kiwi-born principal Ty King-Wall with a nervous laugh. "The music is very difficult to count, so you have to be right on the ball with it. It's not a regular rhythm and the melody doesn't have strong musical cues, so if you're not counting you can get lost really quickly. Actually, I'm still sorta coming to terms with it in rehearsal."

First performed in 1972 as part of Stravinsky Festival (to commemorate the composer's passing), Symphony In Three Movements brings together two of the last century's great innovators in a short, 21-minute work that has established itself as a landmark in contemporary ballet. By mapping Stravinsky's angular and often confronting music onto Balanchine's muscular choreography, it smashes together Russian and Western, classical and modern technique, and influences from both jazz and the European avant-garde.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

As King-Wall explains, "The score was composed between 1942 and '45 and it's actually compiled from a few different sources, including from a film score he created for a documentary on China and from another film called [The] Song Of Bernadette. Apparently, Balanchine had wanted to use the piece for a long time and decided that the Stravinsky Festival was the right time."

For Ty King-Wall and the 32-strong ensemble, Stravinsky's non-linear style cuts right to the heart of their technique, and in particular to the practice of counting the eights. "I've never been much of a counter myself," he says, "which is a little bit naughty, but I try to listen more to the melody really closely, but with a score like this counting is a necessity."

"With a score like this counting is a necessity."

Fortunately, the Australian Ballet rarely shirks a challenge. Not content to remain within the confines of 19th century fairy tale ballet, the company regularly presents seasons of contemporary works. 20:21 is the latest iteration, bringing together shorts by the aforementioned Balanchine, the much-loved Twyla Tharp and the company's own resident choreographer Tim Harbour.

"These are the kinds of things that people will come and look at and go, 'Well, that completely changed my perception of ballet,'" King-Wall contends. "It's very energetic, very raw and visceral. It's kinda sexy too. It's important that we keep doing this stuff, especially work from currently practising choreographers, otherwise the form just kinda stagnates and it's almost like curating a museum."

For the dancers, taking on newer works and dealing with less obviously balletic scores is clearly stimulating, especially when it involves a live orchestra (in this case Orchestra Victoria in Melbourne, and Opera Australia and Ballet Orchestra in Sydney). "There's a bit of an edge to it. You're doing live theatre, so you're aware that anything can happen, but live music adds a dimension. You really have to be on your toes, so to speak."

Doubtless this will also be true for audiences; but that's what keeps the ballet alive.