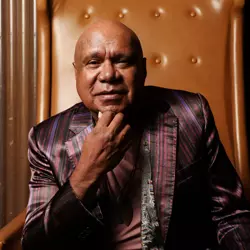

Archie Roach

Archie Roach"I'm lucky that I have music and am able to get it out through songs. Some people don't have that luxury.” And with that, Archie Roach flashes a shy smile, his eyes flicking off into the distance.

Being philosophical and having perspective is something that (hopefully) comes to us all; it's just that most of us won't ever have to endure the process of getting there in public. For an ARIA-award winning singer-songwriter and high-profile indigenous identity, no such anonymity is available. However, Archie Roach's 2010 'year from hell' has brought unexpected blessings and given birth to an album of gospel-flecked songs of recovery and newfound joy.

Into The Bloodstream is Roach's record of pain; and yet it is anything but shrouded in darkness. “I didn't think I was gonna do another album again,” he admits, “but working on this album, writing the songs and singing them, gave me the incentive to pick myself up and carry on.”

Following the sudden passing of his lifetime partner, fellow musician Ruby Hunter, in early 2010, Roach's universe imploded. Things didn't exactly improve when he suffered a stroke while giving music lessons with Shane Howard at Turkey Creek, an isolated Kimberley station eight kilometres from the nearest medical help. The trilogy was then complete when he was diagnosed with lung cancer and had half of his lung removed.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“I don't know if anyone really thinks about their own mortality until something comes along and questions it,” he says. “You really start thinking about things. Y'know, what am I going to leave? Even doing a will. I never thought about that really, until this.”

Of course, Roach is not speaking merely of back catalogue here, even if his does include the now iconic song Took The Children Away. “I really think that everybody, whether they're in the public eye or not, leave behind something, whether that be good or bad, and I really wanna leave something good. Even if I wasn't known and never created music it would still be the same. I wanna leave something meaningful.”

The triple-barrel tragedy of 2010/11 has clearly triggered a complete existential overhaul for Archie Roach. For a man who has made his living in the competitive and vanity driven business of music, having to re-learn guitar post-stroke and adjust to being without Ruby sharpened his focus. “Things that bothered me, that I thought were a worry, are just meaningless,” he declares. “A lot of petty things in my life that seemed to weigh me down just don't anymore.”

The result? A kind of freedom, a lifting of the pressure to perform. “I can now start writing whatever I like,” he smiles. “I've always liked gospel and soul music but ever since I had my first album I've felt that I had to keep writing that type of song about loss and suffering but now this had freed me completely. If I feel like doing something jazzy, I will.”

Listening to Into The Bloodstream you can hear the shackles unbuckling. It is rich in soul, in subtleties and medicinal joy. It is a document of transformation, a map in song of the road to recovery. As Roach himself observes, “This is the first album of mine that's had some direction. Previous albums were just collections of songs that seemed to work together. This was a deliberate attempt to write some songs with a more uplifting feel.”

Drilling further down, Roach explains, “It's like, when you think of places like New Orleans and the jazz music at funerals. They start off with the slow sorta trumpet, tromboney thing and then come up with this really uplifting thing towards the end.”

It's a pretty simple idea, one that many of us will understand; but part of that transformation comes from the doing, the sheer commitment of getting a record in the can. As far as Archie Roach is concerned, the act of making Into The Bloodstream was as crucial as the end result. “The more we got into it each day, the more I understood it. It became, for myself, a redemptive thing,” he recalls. “And working with other people was interesting too. Y'know, we'd sit around and listen to what we'd recorded and, yeah, it brings you out of yourself.”

Away from all the emotional and philosophical hurdles, there was also a physical challenge. Roach's stroke left him wheelchair bound for a time and, even after he had trained himself to walk again, his right (strumming hand) remained stubbornly inflexible. “I couldn't play the guitar at all and I had to work to get it back. I still can't play the way I used to but it's good enough,” he adds. “Y'know, sometimes your hand doesn't do what your brain tells it to.”

Likewise with his singing voice: the loss of half a lung and the resultant 'breath issues' have created ongoing problems for a singer renowned for his smooth, deep croon. “I asked the doctors before they operated whether it would be an issue but they said there's no need that should happen,” he explains. “But I have found that I have to work on my breathing a bit more. It shifts a bit what you have to do. The way you sing is a little different. You sing from different areas, try to take a bit of stress off your lung.”

With a new album and plans for large-scale festival shows incorporating full band and choir, Archie Roach once again finds himself at the start of the music industry cycle; media commitments included. He laughs gently at that, saying, “Yeah, I didn't think I'd be doing this again either. It's still strange because I'm never totally comfortable talking about myself. My nature is not to. I'd rather talk about something else or someone else who's influenced me in my life.”

Of those who have, Ruby Hunter is first and foremost. An ARIA-nominated, Deadly-winning artist in her own right, Hunter also appeared with Roach's other great musical mentor Paul Kelly in the film One Night The Moon. It's a link that Roach acknowledges with a deep, wry chuckle. “I always mention Paul Kelly because he really got me into the music industry. As I always say, I don't know whether to punch him on the nose or kiss him on the cheek.”

Sitting across the record company boardroom table from Archie Roach you cannot help but notice how thoroughly ambiguous he is about the role he finds himself in. However, even in ambiguity there is a kind of perspective, one which allows him to deal with private grief in a public space. “Before I did my first album, which I really didn't wanna do, I maybe would have thought I couldn't handle it. But now, I really think it's important that it's out there and people ask me questions because there are some people that don't know how to deal with it, or are still going through it, and maybe in some little way I can encourage them.”