The Beatles

The BeatlesThe now-ubiquitous nature of digital media means that we, as an entertainment-craved society, have seen a lot of things that were once vital parts of the music discovery process become far less valued.

Despite a growing resurgence in vinyl and CD purchases, physical media libraries have dwindled, the communal nature of visiting music stores is less commonplace, and singles are rarely a tangible product.

Likewise, listening stations have fallen by the wayside and – thankfully – so has the concept of buying a record to find that it's front-stacked with one killer track and a bunch of filler cuts.

This isn't to say these things have disappeared completely. After all, there are still many music lovers fighting the good fight when it comes to supporting record stores, buying physical copies of their favourite artists' music, and diving head-first into an experience not offered by streaming platforms.

However, one of the more unexpected victims of this streaming media landscape is the hidden track.

What Is The Hidden Track?

As the name suggests, a hidden track is just that – a song that is hidden from the listener in some way.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

This could be as simple as just not listing the track on a record sleeve, added as a bit of a bonus to another song, or it could be done in a method that is a little bit more ingenious.

However, the story of the hidden track is one that can be chalked up to pure accident. If you've ever spun a copy of The Beatles' 1969 Abbey Road, you'd probably be aware of the closing tune, Her Majesty.

At just 23 seconds, it's over in a flash and was originally written as something of a joke by Paul McCartney. After listening back to the Abbey Road Medley that closes the album, McCartney suggested it be axed. However, engineer John Kurlander had been advised by the band's manager, George Martin, to not cut anything.

Deciding instead to leave Her Majesty on the final tape – albeit it with 20 seconds of silence preceding it – McCartney ended up approving the new result, and it was included on the final record, albeit left off the track list.

However, one of The Beatles' previous efforts may have also been an originator of the hidden track.

When A Day In The Life from 1967's Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band came to a close, it was followed by a high-pitched tone and a bunch of studio chatter. Cut into a locked groove at the end of the album, it was intended to play endlessly (or at least until you lifted the needle from the record player yourself).

Hiding In (Not So) Plain Sight

As the years continued though, so did hidden tracks. Of course, when it came to formats like vinyl records, it was often easy to physically see the hidden track. After all, if the sleeve lists six tracks on side A and you can see seven areas where the music will be playing, there's a good chance you're about to have a hidden track coming your way.

This meant that musicians had to be a little bit sneakier about it. In 1973, UK comedy troupe Monty Python released their fourth record, The Monty Python Matching Tie And Handkerchief.

Featuring sketches from their Flying Circus series, the record lacked a track list, so fans were left to simply play the album as intended. However, this was merely a set-up for confusion, because the cunning folk at Monty Python HQ had decided to cut the B-side with a double-groove.

This meant that depending on where you dropped the needle, one of two collections of audio would play – effectively turning it into a 'three-sided' record.

It's worth noting, of course, that not all hidden tracks were made to confound the listener. For example, The Clash were supposed to give away copies of their track Train In Vain as part of a promotion with the NME.

However, when the deal fell through, it was tacked onto the end of 1979's London Calling, despite the sleeves having already been printed.

The Hidden Track Reaches Mainstream Prominence

When the compact disc entered the market in the early '80s, the prevalence of the hidden track began to rise once again. One could argue that this is where the hidden track's popularity really took hold, and by the '90s, it had become something of a cultural phenomenon.

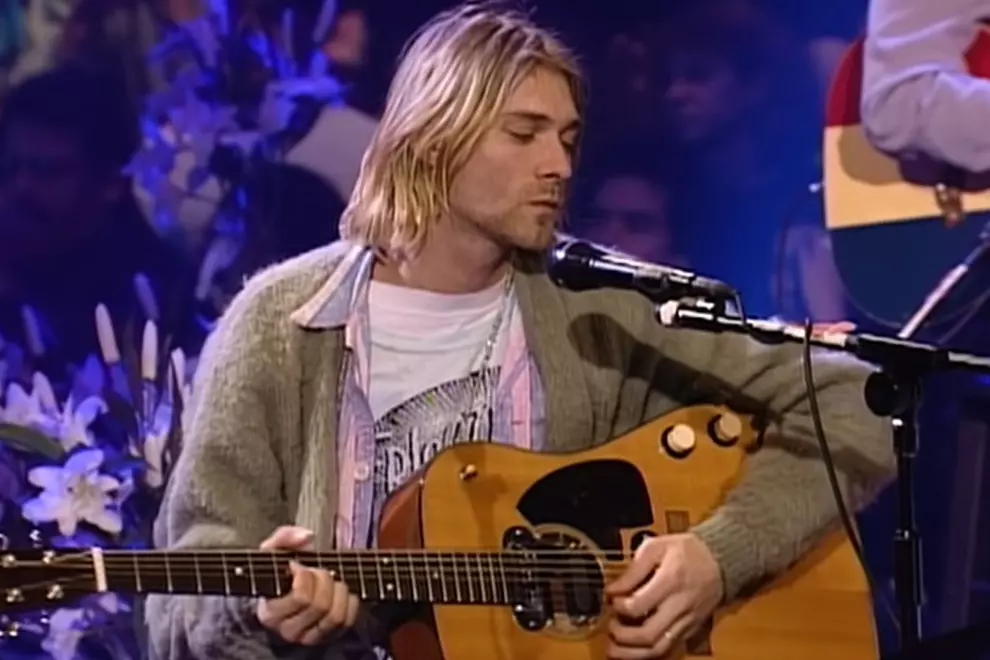

One of the most famous examples came in 1991 when Nirvana released their Nevermind record. Famously knocking Michael Jackson off the Billboard charts and winning a handful of Grammys, the album was stacked full of counter-cultural anthems for generation X.

However, after the plaintive acoustic cut that is Something In The Way, ten minutes of silence follow before the noisy Endless, Nameless plays out. "It's for that person who plays the CD, it ends, they're walking around the house and ten minutes later... Kaboom!" joked Geffen Records’ vice president of marketing Robert Smith.

Initial copies of the record didn't feature Endless, Nameless, and Kurt Cobain was reportedly so disappointed that he demanded it be included on all future pressings.

The following year, 'Weird Al' Yankovic lovingly took aim at Nirvana with Smells Like Nirvana from his Off The Deep End album, which aped the original's artwork as well. The imitation continued to the very end, with ten minutes of silence following You Don't Love Me Anymore, before the six-second cacophony that is Bite Me followed.

Also in 1992, Nine Inch Nails released their Broken EP, which ended up winning two Grammys for the songs Wish and Happiness In Slavery. But initial pressings featured six songs on a regular-sized disc, before covers of songs from Adam And The Ants and Pigface were included on a three-inch mini CD.

Though not hidden tracks per se, frontman Trent Reznor discovered record store owners were selling the discs separately, and decided instead to put the songs at the end of the EP going forward.

So he did. In fact, he placed those cover songs as track 98 and 99, meaning that listeners would have to listen to 92 tracks comprising one-second of silence before they were heard. This later became a common trope, with Marilyn Manson adding Empty Sounds Of Hate as track 99 at the end of 1996's Antichrist Superstar.

While popping tracks at the end with little notice (or after myriad blank tracks), started to become commonplace, other artists continued to find a way to be a little bit clever about it all.

In 1996, Frenzal Rhomb's Not So Tough Now album took a very novel approach. While the record sort of ends at track 17, an additional 18th track is included, though the rear artwork lists a total of 53 – with all the extras features different variations on a similar theme.

So, tracks like Secret Track Dub Mix, The Secret Track So Secret We Didn't Know It Was There Till We Counted Them Secret Track, and The Biggest And Most Amazing Super Duper Extravaganza Of An Extraordinarily Large Maybe Even Humongus Secret Track Secret Track And This Is The End Of This Madness So Go And Read A Book are all listed as real tracks.

However, each song lasts four seconds, and when combined, they make up a song later titled Best Of Secret Track (and informally called Ben) when included on their We Lived Like Kings (We Did Anything We Wanted) compilation.

In 2010, Oasis' singles compilation Time Flies closes with Sunday Morning Call appended to Falling Down as the final song on the record. Reportedly, this was done since its songwriter, Noel Gallagher, detests the track, but the band still wanted to ensure all singles were included.

Another method of hiding songs on albums made use of what is known as the pregap. For years, when you inserted a CD into your player, the audio on the CD was preceded by roughly two seconds of silence – called the pregap.

Soon enough, compact disc manufacturers worked out a way to add secret songs into that pregap. While not all players could access these songs, the traditional way to do so was to pop the CD in your player and effectively 'rewind' the disc (by holding down the rewind button) until you reached the start of that audio.

It was used by countless artists over the years, ranging from the likes of Kylie Minogue, the Hilltop Hoods, Blur, Pearl Jam, Bloc Party, and others.

Queens Of The Stone Age added one to their 2002 album Songs For The Deaf, with a track called The Real Song For The Deaf featuring heavy bass – ostensibly designed to be 'felt' by those with hearing impairments. This was extra surprising, given that the sleeve physically lists Mosquito Song as the hidden track, which itself follows after some additional content at the end of its preceding song.

One of the most famous pregap tracks was featured on Songs In The Key Of X, the 1996 compilation released to cash in on the hype of The X-Files.

A massive seller, the record's opening track actually featured two secret tracks recorded by Nick Cave and the Dirty Three, with Time Jesum Transeuntum Et Non Riverentum and their version of The X-Files Theme relegated to the secret position.

These songs were actually hinted at in the record's liner notes, where listeners were notified that "Nick Cave and the Dirty Three would like you to know that '0' is also a number."

Other pregap cuts have been a tad sneakier. The full title to Soulwax's Most Of The Remixes album specifically points out how the group had lost a remix they had made of an Einstürzende Neubauten song. However, the remix can actually be found in the pregap to the second disc.

There were other methods for hidden tracks as well. Marilyn Manson included an untitled song in the multimedia files of his Mechanical Animals album, meaning you could only hear it if you opened the track on a computer.

Meanwhile, Nine Inch Nails' Ghosts I-IV album featured multi-track files included on a bonus DVD, meaning you had to construct the songs yourself to properly hear them.

While Tool also included unlisted songs on a few of their releases, a 2011 newsletter hinted at the ‘ultimate’ hidden track, with the group having reportedly concealed a song called Problem 8: The Reimann Hypothesis on a piece of limited Tool merchandise, limited to around 30 copies.

“Most people don’t even know they have it,” the newsletter said. “It’s been staring them right in the eye on a near daily basis. The reason they aren’t aware of it, is because they’d never think to play it.”

To this day, it remains unclear if the song is even real, or if the newsletter – which has long been used to help facilitate April Fool’s jokes from the group – was just having us all on.

Sneaky Successes

Logically, one would almost expect that the very notion of hiding a track on the record indicates that the artists didn't particularly foresee a huge commercial impact for them.

After all, can you imagine if Nirvana had relegated Smells Like Teen Spirit to be a hidden track instead of the opening track and lead single?

But in some instances, these hidden tracks have ended up being far more successful than their creators could ever have imagined.

In August of 1993, US rock outfit Cracker released their second album, Kerosene Hat. While its lead single Low ended up being an alternative rock radio hit, third single Euro Trash Girl was one that had been a live favourite well before the record was released.

However, with 12 tracks already, the group's label thought they were stacking the album too full of material. In response, they added a couple of silent tracks before Hi-Desert Biker Meth Lab showed up, and then popped Euro Trash Girl at track 69.

They also included two more songs at track 88 and track 99, though Euro Trash Girl was the most successful. It warranted a music video, hit No. 162 in Australia, and even found itself covered by electroclash outfit Chicks On Speed.

In 2000, the Eels' third album Daisies Of The Galaxy was promoted by the song Mr. E's Beautiful Blues. Notably though, anyone buying the record would have been confused given that it wasn't listed.

This was because group mastermind Mark Oliver 'E' Everett had written the song after the record was wrapped, and the label requested it be issued as a single. It became a moderate success, went on to chart in triple j's Hottest 100 of 2000, and is currently their fifth most-listened to song on Spotify.

One year earlier, at the 1999 Grammy Awards, the most-nominated artist was Lauryn Hill, who took home awards for half of her ten nominations. One of the awards she didn't take home was Best Female Pop Vocal Performance, for which her cover of Frankie Valli's Can't Take My Eyes Off You was in contention,

This nomination actually made history given that it had been included as a hidden track on 1998's The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill, making it the first hidden track ever nominated for a Grammy.

The Decline

As the general consumption of music slowly moved away from the physical to digital in the 21st century, the hidden track all but died out when it came to mainstream releases.

The main reason for this was due to the fact the songs were no longer 'hidden', per se. Much like how the grooves could be counted on a vinyl record, CD players had already ruined the fun when they told listeners that 12 tracks were present despite the 11 on the sleeve.

But digital listening meant that the playing field had changed again. After all, when someone ripped a CD to their iPod and noted that the final track had a 30-minute runtime, the chances were good that a bonus song was about to be found therein.

Likewise, if one went to the iTunes Music Store back in the day (or their preferred streaming platform of choice these days), the tracklist would be spoiled even before listening.

These days, it's easy to find hidden tracks on streaming. My Chemical Romance's The Black Parade specifically appends the title of the of the song Blood with the words 'Hidden Track', and Alanis Morissette's Jagged Little Pill closes with a conspicuous addition of a second version of You Oughta Know followed by the gorgeous a capella cut that is Your House.

Meanwhile, Cracker's Kerosene Hat omits the blank songs and adds the secret cuts to the end of the record, the fact that Frenzal Rhomb's Not So Tough Now features 53 songs lets the cat out of the bag, and Marilyn Manson's Antichrist Superstar ending with an untitled song ruins the fun a little bit.

However, the reverse is also true. While many of these secret songs ended up making the leap to digital and streaming platforms, many haven't.

You can't hear 'Weird Al' Yankovic's Bite Me, nor can you hear Limp Bizkit's Blind after their cover of Faith, and lovers of Australian rockers The Fauves' Future Spa album might find it weird to see Everybody's Getting A Three Piece Together tacked onto the end of the album without the seven-minute police interrogation that follows.

However, the prevalence of streaming has notably made some of these hidden tracks more accessible than before in some instances. With it being easier than ever to release new material, some of these hidden tracks have been excised from their original releases and placed onto new compilations.

While Ash's 1977 no longer ends with Sick Party, one can find the song at the end of the Collector's Edition of the record, and likewise, one needs to go to the deluxe edition of Nirvana's In Utero to find Gallons Of Rubbing Alcohol Flow Through The Strip, which had been named the 'Devalued American Dollar Purchase Incentive Track' on non-US versions of the record.

Ironically, as hidden tracks have fallen out of favour on new releases in the digital age, some artists have instead taken a more traditional approach.

Though Jack White's 2012 album Lazaretto is just 11 songs long, the vinyl edition made itself desirable to lovers of physical media by way of hiding numerous secrets in the album.

While each side of the record closes with a secret untitled track, the record's centre labels also feature songs pressed into them. Additionally, the A side of the record is designed to play from the inside out, while Side B's opener – Just One Drink – is made to have two different introductions, depending on where the needle is dropped.

Though it appears clear that – at least for the foreseeable future – the hidden track will remain absent from most mainstream releases, and its mention will likely evoke surprised claims of "Oh, yeah…" from those around to experience it in its heyday, it will remain a fond memory to those who appreciate physical media and its myriad capabilities.

To the media hoarders among us, maybe now is the time to get out your much-loved CDs and records, and let them play to the end, allowing the latter to tell you if there's a locked groove, or the former to tell you if there's extra content before or after the standard playtime.

To everyone else – and especially to the musicians amongst us – let's not let the hidden track die, lest the fun of musical discovery die along with it.