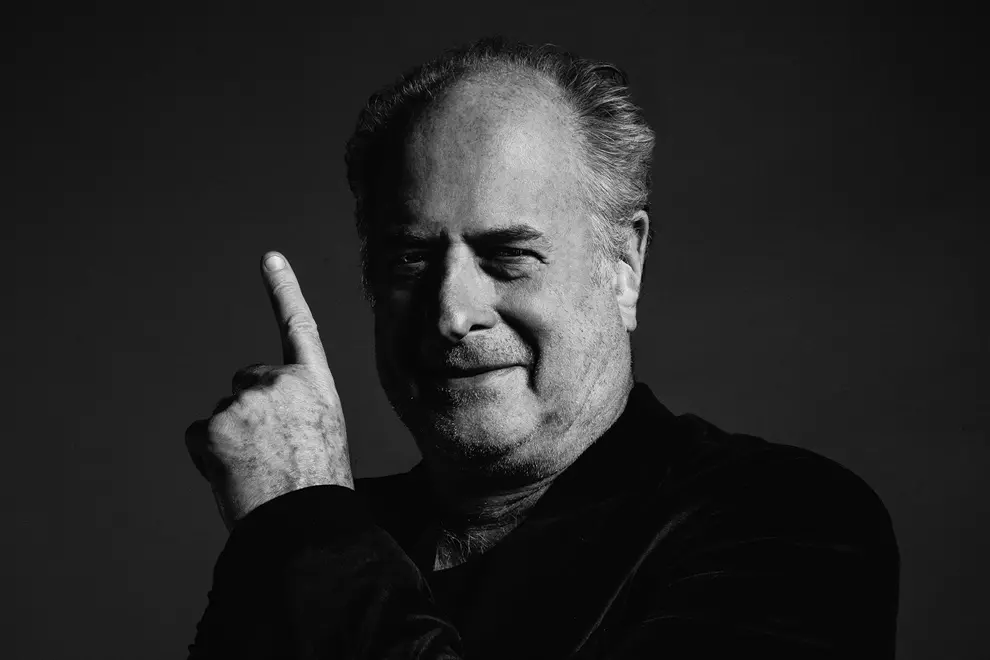

Michael Gudinski

Michael GudinskiThe 1970s are known as the birthplace of the modern-day Australian live music scene, and the launch of the Gudinski podcast this week has revealed some of the details of the commercial fights that punctuated a crucial time in music history.

Chronicling the life of Mushroom’s Michael Gudinski and narrated by his daughter Kate, the podcast has revealed stories from industry heavyweights, discussing for the first time the turf wars that punctuated the early days of pub rock.

Labelled by Gudinski himself as the “core of the Australian music scene”, 70s pub rock created the commercial bedrock that built an industry. The 70s were a great time for the scene to blossom - cheap beer, loud music, and rough crowds came together to create the perfect night out, and venues were only too happy to open their doors to capacity and beyond.

Daddy Cool and Mondo Rock singer Ross Wilson explained: “It was pretty wild. You didn't have all these health and safety issues like they have now, like a promoter could pack a room with as many people as they wanted.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“I remember going on tour and we're playing up at Coffs Harbour, it was really hot and the place was absolutely jam packed. And I came offstage, and I was spinning out from the tobacco smoke in the room, and it would take me a week into a tour for me to feel normal. I had to get used to the nicotine. I got a nicotine habit just staying in the room, you know, and your clothes would reek, it'd be sweat-riddled, and you get up in the morning and smell like cigarettes, and that, that was the norm.”

The scene was robust but also rowdy, as current-day Cold Chisel and Midnight Oil manager John Watson explained.

“It's impossible for people in 2024 to comprehend just how bloody-minded you needed to be to break through as a band or a solo artist in the 1970s or early 1980s.

“It involved playing five gigs a week, night after night. Often to really drunk and really dangerous audiences. It's not a coincidence that you had this entire generation of bands with front people who utterly could not be ignored. You know, say what you like about Chrissy Amphlett, say what you like about Peter Garrett, about Jimmy Barnes - these are people who cannot be ignored. They grew up in a really Darwinian struggle of standing on stage to go, ‘No, no, you sit down, you stand there, you shut up. You listen to me.’”

Industry stalwart Mark Pope recalls working for promoters at the time, collecting band fees in cash.

“Back then, there was no Electronic transfers. I was still living at home, and I was picking up cash every night. So on a weekend, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, night. Back then, it was a lot of money. I had about twenty-five grand, and my mother was so freaked out, she'd hide it in the freezer, or she'd hide it in the knitting and all this sort of stuff. It was a lot of cash to be responsible for.”

Where there’s money, there are promoters, and as the scene grew, Michael Gudinski’s stranglehold on the live music scene via his booking agencies Premier in Melbourne and Harbour in Sydney had new challengers emerging, including Sydney’s Dirty Pool, operated by John Woodruff, Ray Hearn, and Rod Willis.

Gudinski biographer Stuart Coupe said: “They [Gudinski’s agencies] were the booking agents that any aspiring Australian artist wanted to be on, you know, ‘I'm a Premier artist, I’m a Harbour artist’. The two offices work very closely together. Sydney artists’ shows would be put together in Melbourne by Premier and vice versa. It was an early part of Michael's emerging, all-encompassing approach to the music industry.”

“Dirty Pool was trying to undermine this perceived dominance that Premier Harbor had. And the way that they would dictate to venues they thought they had too much power. And on the Gudinski side of things, they were going, who are these upstarts? They're muscling in on our turf.”

Dirty Pool tried to break the Gudinski stranglehold by introducing the ‘door deal’ where artists would be paid based on how many people attended the show. According to the podcast, there were stories of bands being paid $250 for a show, not knowing the venue had actually paid $1000, and someone on their team had pocketed the rest without disclosing.

Instead, Dirty Pool would go to venue owners and negotiate their own rates, which often meant the bands would earn up to 90 per cent of ticket sales. Bands then talked to each other, leading to questions about why they were being paid less, creating a rivalry between the agencies, with some labelling them ‘the music mafia’.

“And that was war. That was on between Premier, Harbor and the Dirty Pool agency,” said Stuart Coupe. “None of these people were saints. So they were not above if there was a fight on; they were in the ring, and they were taking it on. It was nasty, it was vindictive, it was a take-no-prisoners assault on each other.”

Bands recalled shows being inexplicably cancelled because they were with the ‘wrong’ agency, and stories abound of dirty tricks played between the companies. John Watson (who wasn’t there at the time) said the stories of promoter wars are legendary within the music industry.

“The stories - they've grown taller with the years,” he said. “What would happen, allegedly, is that the band Midnight Oil will come into town. They're going to play the pub around the corner for five bucks, and just mysteriously, Split Enz or Skyhooks, or JoJo Zep and the Falcons, or whoever the Premier band is ends up playing sort of the slightly bigger venue for four bucks. And, you know, they've got the only billboard in town, and all the posters for Cold Chisel keep getting torn down, and the tyres mysteriously get let down on the truck and on and on and on.

“It’d make a fantastic movie, although I think you’d probably have to change all the names and identities to protect the guilty. It was not a place for gentle souls. This was not a place for playing nice. All's fair in love and war in those situations. Because that was the rules by which that game was being played. It was a different game (to today).”

The ‘cleaning up’ of the live scene had some lasting impacts, which carried through to today, with much more transparent financial practices helping artists. Cash is no longer king, and door deals created a new economy where bands were paid based on their audience and commercial worth.

To hear the whole story, check out the Gudinski podcast, available on the Listnr app or wherever you listen to your podcasts.