Anohni

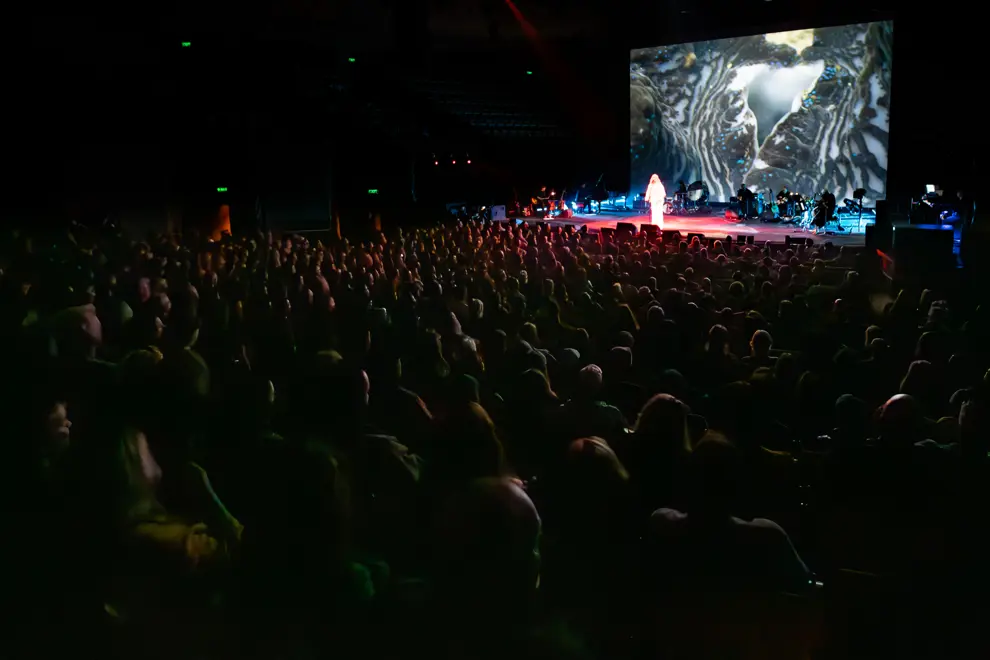

AnohniInside the shell of the Sydney Opera House, beneath sails that once suggested flight, we witnessed a descent. Not into silence, but into grief. Mourning The Great Barrier Reef, ANOHNI’s final performance in Australia with The Johnsons as part of Vivid LIVE, was less a concert and more a ceremony of witness — a requiem for the reef, a reckoning with ourselves.

What unfolded was a deep, slow ache, carried on by her voice, which still cuts like wind over water. Backed by The Johnsons and encased in cinematic projections of the reef's past splendour and current distress, ANOHNI summoned not nostalgia, but clarity.

These weren’t just pretty pictures. They were elegies. Technicolour schools of fish flitted across the screen only to dissolve into footage of bleached coral and empty seabeds. Grand montages danced between beauty and desolation, colour and colourlessness, creating intimate character elegies for lonesome turtles and solitary nudie branches.

Between songs, testimonies from marine biologists and filmmakers like Charlie Veron and David Hannan punctuated the silence. They spoke not with anger, but with something heavier: the quiet authority of people who have watched something they love slowly die.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“We don’t want to talk about science,” one says. “We want to talk about hope.” But hope feels fragile here. “I was always convinced man was going to be able to overcome this,” another admits. “I don’t think that anymore.”

Then ANOHNI sings Hopelessness, and suddenly the ecological and emotional collapse align. The performance feels less like an explanation and more like an embodiment — a reminder that grief, when sung, can sometimes say more than any data point. Another testimony about diving off Heron Island at 18. “I’d never seen anything more beautiful.” The statement hangs in the room, too human and too painful to refute.

Later, as voices onscreen remind us that “the easiest way to create mass extinction is through the coral,” ANOHNI slips into Cripple And The Starfish. “It’s true I always wanted love to be filled with pain,” she sings. “If I cut off my fingers, they’ll grow back like a starfish.” The simile, in this context, scrapes against the bone. The coral won’t grow back. Not now. Not like it used to.

The arrangements are sparse, spectral. A cappella phrases hover like mist: “Your hatred for me makes my eyes round and wide. I just want to close these holes.” Then the saxophone arrives, low and mournful, and she moves into Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child. Her rendition is raw, staggering. It doesn’t ask for sympathy. It asks for candour.

There is no room for denial in this space. Just voices, some spoken, some sung, insisting on the gravity of the moment. “We’re going down this path to ruin and destruction, and we’re doing nothing about it,” one expert says. “This is a really bad thing that’s happening. We could stop this. But we’re not.”

ANOHNI counters that with You Are My Sister, a song that still manages to carry warmth, even when surrounded by rot. Then It Must Change, urgent, pleading. Change is not a concept here. It’s a cry.

The scientists return onscreen. “We could’ve been in a much better place if we’d acted 20 years ago… now our generation and future generations will have to deal with this greed.” The line hits hard. It’s not just about coral. It never was. The reef becomes a symbol for all we’ve let erode — the ecosystems, yes, but also the faith that we might still turn things around.

“I’d advise anyone who wants to see the Great Barrier Reef to do so in the next five years,” a voice says. Then, with gentle devastation: “It’s like you mourn when someone you love dies.”

ANOHNI continues, cloaked now in a glinting, translucent shroud, barely visible beneath the light. She sings Scapegoat. “You’re so killable.” It is not an accusation. It is an observation. And maybe it is not just the coral, but our capacity for care, for kinship, that is at stake.

“What’s coming is the inability to be resilient,” we’re told. The testimonies slide into a kind of ecological poetry. “Every time we get one of these mass bleaching events, it hurts.” There is a brief, almost unbearable pause. “It’s really difficult to talk about that grief—as with all grief—but it’s real.”

Then Another World. Her voice rises, not above the grief, but through it. “I need another place, I need another world.” We’re not escaping. We’re mourning what we’re still losing.

The final notes are not a warning. They are a directive. “Find the place in nature that you love,” a voice on the screen instructs tenderly. “Go to it and think of it as your kin.” Then the last lyric: “I have heard the crying sound. No one can stop you now.”

This wasn’t just ANOHNI’s last performance in Australia with The Johnsons. It was an elegy for the Anthropocene. And if we were listening — really listening — it was also a challenge. To feel. To grieve. And maybe, still, to act.

Just before the lights dim for good, ANOHNI returns alone to the piano. The room holds its breath as she plays Hope There’s Someone. Stripped of everything but her voice and those keys, it becomes a final, aching plea. Her voice trembles at the edges, intimate and vast all at once. The song ends, and she sits in stillness for a moment. Then, returning to the stage, she blows kisses to the crowd — gestures of thanks, of love, maybe of farewell.