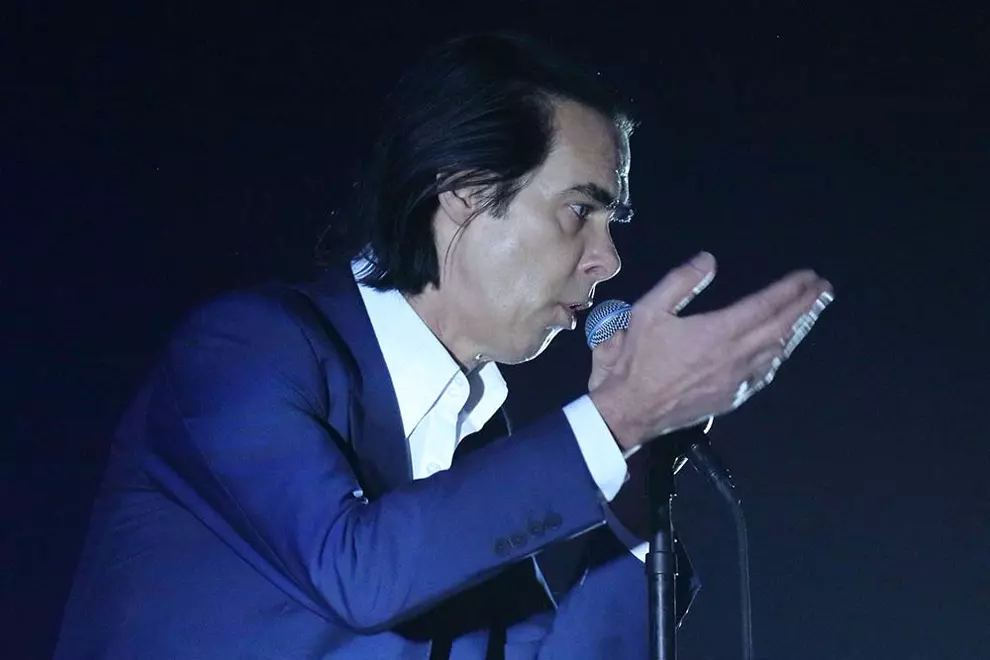

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds

Nick Cave & The Bad SeedsI once heard an off-the cuff – and what seemed like a broad-sweeping statement at the time – about Nick Cave many years ago. And that was: the man is a god. It seemed so bold, too bold, to not even suggest that Cave was akin to divinity; that he was, in fact, not of this world.

For those familiar enough with his music in its many forms over the decades, it’s likely no one would argue that Cave rightly belongs in the Australian music lexicon; a name – and a presence – behind some real meaty hits. Into My Arms, Where The Wild Roses Grow, Red Right Hand, O Children. These are all titles that claim a knowing in likely many music lovers, even if it is merely peripherally familiar.

But for the devout followers, Cave achieved god-like status long ago, and to them this statement is all but an indisputable truth that seems futile to argue against.

The lore of Cave is what continues to pull the curious and newcomers to his personal triumphs and tragedies, his albums, his projects, his shows, as though his arms that have carried the whole spectrum of joy and heartache are gently sweeping those who need to hear him, gradually throughout the years with each iteration and incarnation of the man and his players.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

There are also the faithful who remain for it, crave it, need it, to see him build upon his artistic pilgrimage year after year and expands the tapestry of this enigmatic man’s musical odyssey with every thread.

So, in his fourth decade with the Bad Seeds, after 18 albums, globe-trotting tours, the interrupting highs and lows of life, Cave and the crew are back after a nine-year absence from Australian and New Zealand stages before a lengthy stint overseas to make 2024’s Wild God blossom in Europe.

On a balmy Tuesday evening in Brisbane after the city recovers from a blistering, long-weekend heatwave with a blanket of low cloud above the RNA Showgrounds, expectations are high but also assured that this band’s performance will be both resonant and ravaging, a spiritual conflagration of sound, sorrow and cathartic release.

Setting the tone for this reckoning is New Zealand’s Aldous Harding. This enigmatic alt folk artist has been a constant and consistent music producer and performer for almost a decade, but her off-kilter delivery and otherworldly vocal have only fortified. She is not self-conscious about a good throat clear, which can’t be giggled at because really her voice is faultless.

Throughout her set, she retains something intimate and close despite the openness of this large outdoor venue. “This next song is horrible – you'll love it” are the sort of cynical quips that make her the perfect opener for tonight’s main event.

And then it’s over to them, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds. There are gigs, and then there are Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds gigs – experiences that feel less like music shows and more like something ceremonial.

From the moment they open with Frogs, the band sets a tone that bizarrely feels both ancient and urgent. A four-piece gospel-inflected choir, alongside the Bad Seeds, lend lush harmonies that swell the set beyond a performance into a collective catharsis.

The stage only minutely fractures the gap between Cave and the crowd when he ditches hiding behind the mic stand, lithely and nimbly working the front row in his trademark black suit and slip-ons. It’s at this point he advises not to touch him too much for fear of “sexually harassing me in the workplace”.

So, there is lots of laughter, but also a deeper recognition: in a career built on darkness and mercy, the lines between spiritual seeker and musical shaman have long blurred. While a lot of the set pulls from the band’s 18th studio album Wild God – a record lauded for its exploration of redemption, grief and hope, and described by Cave himself as “an antidote to despair” – there are loads of fan favourites early on.

Songs like O Children are fragile one moment and fierce the next, with Warren Ellis’s violin slicing through the sonic landscape like an oracle’s cry.

Tupelo ignites a primal fervour, you can almost feel the heartbeat of the crowd. Joy – with its refrain “we’ve all had too much sorrow, now is the time for joy” – feels like an excision of weight, its central motif lingering long after the last note lilts up into the thick night air. Its sparseness also provides a perfect point in time for punters to tell one chatty old mate to “shushhhh”.

Even in an outdoor venue, that’s how enraptured and religiously present the crowd is. Red Right Hand is just a damn sexy song, and a clear favourite that inspires the most exuberant sing-along.

Cave & The Bad Seeds do not exit quietly; the encore runs deep, with a cover of The Young Charlatans’ Shivers (later made famous by Cave and The Boys Next Door); Papa Won’t Leave You, Henry; The Weeping Song (in which eventually everyone nails the syncopated claps); a killer Henry Lee with one of the incredible backing vocalists giving soul to PJ Harvey’s part, and Skeleton Tree offering a solemn reverie before the final ascent with just Cave on stage for Into My Arms.

It is moving and magic to see him tear up during the latter, and to share in it, too.

As these last notes fade and the night closes in, there is a sense of having not just heard every note but felt every intention that each held – in the chest, in the lungs, even in the spaces between breaths.

This Wild God iteration of the Bad Seeds feels like a band in its absolute prime. Cave – now 68 – commands the stage with an unerring intensity that belies his years. Whether prowling or poignant, authoritarian or adoring, his presence anchors the wild, beautiful chaos that surrounds him.

Cave leaves you believing – if only for a night – in the power of collective transcendence and momentary respite from a world that is reeling from the very human sins he so deftly gives voice to and navigates so skilfully through his craft. And sure, he could actually be some kind of god.

This piece of content has been assisted by the Australian Government through Music Australia and Creative Australia, its arts funding and advisory body