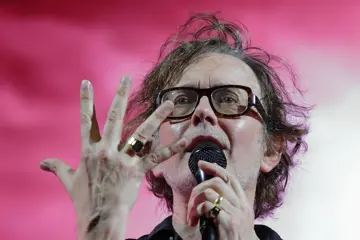

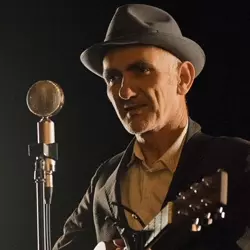

Paul Kelly

Paul KellyThere's an anecdote in Paul Kelly's 2010 memoir How To Make Gravy which places him in inner-city Melbourne in the late '70s, at the time when he was trying to gain a toehold in the then bustling music scene with his new outfit The Dots. That band's original guitarist had graduated on to directing TV dramas for Crawford Productions such as Skyways, Cop Shop and The Sullivans, and wasn't averse to scoring his mates paid jobs as extras, and Kelly recounts getting a cheque from one of these gigs and taking it straight down to a book shop in South Yarra and purchasing a three-volume, annotated edition of Shakespeare's Complete Works that he'd been eyeing off for ages. You can readily imagine TV extras of the time spending their ill-gotten gains at the pub or TAB, but on The Bard?

That collection of Shakespeare is still one of Kelly's most treasured possessions to this day, and with that in mind it's no real surprise that he's celebrating the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's passing by releasing new mini-album Seven Sonnets & A Song, which finds him putting music to (and singing) six of Shakespeare's sonnets plus a song from his play Twelfth Night. The titular seventh sonnet, My True Love Hath My Heart, is by Shakespeare's contemporary Sir Philip Sidney, here beautifully rendered by Kelly's long-term cohort Vika Bull. It's a definite labour of love, but one that's paid bountiful dividends, even the least ardent of Shakespeare admirers.

"I'm aware that some people find Shakespeare a bit intimidating, or think he's highbrow, or think 'It's not for me' or got put off Shakespeare at school, but I think he's always modern, he's always modern," Kelly smiles. "There's nothing that anyone ever wrote about that he hadn't written about before, so I really wanted to make the record not really 'arty' in any way or have that feeling of (adopts posh voice) 'This is serious art, this is Shakespeare'. I wanted it to be so people could feel it purely and feel it good.

"There's nothing that anyone ever wrote about that he hadn't written about before, so I really wanted to make the record not really 'arty' in any way or have that feeling of (adopts posh voice) 'This is serious art, this is Shakespeare'."

"I guess I got onto Shakespeare more through the plays — I came to the sonnets later. My first experience of Shakespeare was at school when we did Macbeth and I loved it. I always found the language so thrilling and I've been hooked ever since. The sonnets I sort of came to later, and I've picked at them over the years and you find different ones each time, but they're sort of a lifelong companion to have the sonnets, because every time you dip into them you always find something new."

Kelly's love of language and wordplay extends far beyond Shakespeare, and dates back right to the early days of his development.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

"I did Latin at school for five years and French, and my father always had a love of words," he continues. "I think I've got that in common with most of my siblings — we like words, so I always look at the scrambled nine-letter word in the paper and try to solve that. Our mother loved Scrabble — she was a demon Scrabble player — so words were always fun, things to play with.

"That's what poetry is — having fun with words, and I think if anyone epitomises that it's Shakespeare. He had so much fun with words that he made them up all the time! A lot of the words we use are ones he invented. I think it was that time also in the English language when it was both fermenting and fomenting, so people felt free to use words in any way they wanted. I don't think there were people getting upset about grammar or where the apostrophe was or even using new words.

"I always think about today when we he have a tendency, well, even I have a tendency to complain when your children use words the wrong way. Then you think, 'Well, actually, if enough people start using the word that way then that's the language changing', and that's what Shakespeare did. And so many of the words and phrases we use that we just take for granted, like 'method in his madness' or 'brevity is the soul of wit', they're just things that Shakespeare made up that we just think are part of the language now."

Of all the sonnets that Kelly tackles on the album, Sonnet 18 is probably the most familiar, with its opening gambit, "Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?"

"Yeah, that's probably the most popular of his sonnets, so I can't be accused of going for the obscure ones," Kelly chuckles. "Sonnet 73 and Sonnet 18 are really very well known, and Sonnet 60 — 'like as the waves make towards the pebbled shore' - that's one too. I guess they're well-known and popular for a reason, aren't they, because they're very striking.

"But they're very singable as well, that's the thing — they rhyme, and they have very definite metre, and they have a little couplet at the end which can work as a chorus. So they work quite well for turning into songs. The only thing is that for modern ears they can be quite challenging because there's 400-year-old language, but I hear that language sometimes in bluegrass music or old-time country music, just a turn of phrase or placing words in a slightly different order. It's not a big shift."

Kelly's take on Sonnet 18 in particular has a bluegrass feel to the musical accompaniment, which he puts down to mere gut feel and intuition.

"It's just the way the tune came out," he shrugs. "That was the first one I wrote — that was a couple of years now that I wrote it — and it just came out like that. To me it sounded like an old-time Appalachian Mountain song, but that kind of makes sense because I love all that music that developed in America that came from people coming out from England, and they went and lived in the hills. They were coming out in the 17th century and their language didn't change that much in some ways, whereas the language in England changed. But in certain pockets of America in music that language — while it changed of course — kept that cadence, that old-time cadence, and you can sort of hear that in bluegrass where saying 'thee' or 'thy' makes perfect sense in that kind of music.

"I guess it's not so much the words themselves, but the cadence and the syntax, the way the words are placed in a line. I think you can still hear in that some of those old folk songs and old-time songs in America, the language sort of didn't change that much from when it came out so it sounds like a few centuries old. So the Shakespearean language fits it quite well."

Kelly explains that while it wasn't too tough a choice which sonnets he would tackle for the project, their selection was something of an inexact science.

"Again, I didn't make conscious choices saying, 'I have to do this one', or 'I have to do that one', I just generally flipped through the book and then would come across one and I'd have my guitar with me and think, 'I'll see if I can make something out of this', and usually it would just happen really quickly or not at all," he offers. "I can't really say why. It was more through browsing through the sonnets with my guitar in my hand. I mean, I knew all my favourites, so I would probably tend towards them, but I made discoveries as I was reading through. [Sonnet] 138, I wasn't really aware of that one in advance, I just came across it turning the pages and started making up something to it. I want to actually do some more, but they're the only ones I've put music to — six by Shakespeare and one by Sir Phillip Sidney, his contemporary — but I'm just in the habit now of putting poems to music, not just Shakespeare.

"The only thing is that for modern ears they can be quite challenging because there's 400-year-old language … just a turn of phrase or placing words in a slightly different order."

"I guess that all started about four years ago when I got involved with writing a piece for ANAM — The Australian National Academy of Music, the student orchestra with a classical composer — and they asked me to do something with James Ledger. I decided to try and put some poems to music using Australian poets Les Murray and also people like Yates and Emily Dickinson. Plus Five Bells by Kenneth Slessor, another Australian poet. We actually put a record out for that three years ago called Conversations With Ghosts — that was all poems put to music — although that had a more classical sound just by the nature of the collaboration, but that just sort of got me in the habit of putting poems to music.

"For me it was like turning a key. It was, like, 'Oh, that's another way to write a song!' I'd always just written songs with my own lyrics, but I've been writing songs for 30 years so I'm actually just getting sick of my own words. If you can find some good words out there to start with… Writing words is the hardest part of writing songs, so to be able to sort of have the words already and just put music to it was, like, 'Oh, why didn't I think of this before?' I think it's something I'll continue, it's just another string to the bow really, being able to put music to poems as well as write my own songs. I'll always do both anyway, I can't help myself. I still like to make up my own words every now and then, but the pressure's off," he laughs.

Kelly reveals that he made the most adaptations to his version of Sonnet 138, but even then he stayed relatively faithful to the source material.

"That's one where I used a couplet — the last few lines of the sonnet — as the chorus," he tells. "Pretty much the poem is complete though. In another tracks I repeated the sonnet, or repeated part of it, but on this one I made the couplet like a chorus, so Sonnet 138 on the record has more of a song structure with verses and a chorus, and even a little solo on the vibes and the piano."

Kelly recounts that the song from Twelfth Night had already appeared in his canon, while the solitary sonnet not by Shakespeare on the new recording — Sir Philip Sidney's My True Love Hath My Heart — is still pretty relevant to proceedings.

"Again, Oh Mistress Mine [from Twelfth Night] is even further back from the Sonnets, I wrote that about the time I did a record called [2012's] Spring & Fall," he says. "I actually recorded it then, but it was a hidden track on Spring & Fall and I decided to bring it out of hiding for this record. The Philip Sidney one was just a poem I've always loved and it was a sonnet, so I felt like it would fit perfectly onto this record. And as soon as I wrote it I thought, 'Well, a woman has to sing this', and then I thought, 'Vika!' She's got beautiful articulation and I knew she'd do a pretty great job of it, and she did."

Kelly's love of The Bard's work has manifested previously in his work, albeit not quite so overtly.

"Yeah, Desdemona [from 1987's Under The Sun] was based on Othello, definitely," he admits. "And Keep On Coming Back For More from [2014 collaboration] The Merri Soul Sessions is pretty much — well it's not using the words but it's a very similar idea to — Sonnet 147: 'My love is as a fever, longing still/For that which longer nurseth the disease'. That's pretty much Keep On Coming Back For More. So I guess lines and phrases of his have snuck into my songs over the years."

In How To Make Gravy Kelly at one point espoused that Shakespeare's obsession with time had also infiltrated his work.

"Oh yeah of course, I forgot that song from [2001 album] ...Nothing But A Dream, I Wasted Time — 'I wasted time, and now time has wasted me' — that's a straight lift from King Richard II, without the 'doth'!" he laughs. "'I wasted time, and now doth time waste me' — I took out the doth, and kept the rest of it. But he's always been there. And it's not just Shakespeare; if I like a line from poetry or a line from the Bible then why not let that line go around again? That's how folk music works, and blues, a lot of lines keep on coming back. They're like tools or little building blocks, you can use them over and over again in different songs."

As intimated Kelly's love of the King James Bible has also been very influential in his songwriting.

"Yeah, again it's a language, and it's interesting that the King James Bible was put together in 1601, so it's from Shakespeare's era," he reflects. "I think at that time the English language hit a real peak of fertility and invention and cadence that's still ringing down through the language today."