THREE IDENTICAL STRANGERS

It’s the strangest of stranger-than-fiction tales: at 19 years old, three New Yorkers, having grown up in three different adoptive households, discover that they’re identical triplets, separated at birth.

They come to know this through profound coincidence: two of them are introduced by a disbelieving shared acquaintance, these young men suddenly coming face-to-face with a double, a doppelganger. When the story of these separated twins hits the newspapers, a third triplet sees himself, x2, beaming back at him from the page. The three of them meet. They look the same, act the same, have the same mannerisms. The tabloids eat it up. They become minor celebrities. They open a restaurant, where customers come not just for the food, but to see these three men, who look like one, working the room together.

This is, in and of itself, an astounding premise for a documentary. And Tim Wardle’s pic duly takes that as its starting point, Three Identical Strangers effectively beginning as a great yarn, told with a, 'You’re-not-gonna-believe-this,' giddiness. The thrill of this tale turns out to be something like storytelling misdirection, though. From its joyful opening act, the film is soon upended by a string of revelations, which peel back the feelgood façade and reveal the darkness underneath.

Few films need protection from ‘spoilers’ as much as Three Identical Strangers, whose unbelievable story seems all the more incredible if you come in cold. This is both something to commend, but also something that symbolises the limits of the filmmaking. Wardle made the film for CNN, and there’s conventionality to its approach: the talking heads in front of school-photo-esque backdrops, the dramatic recreation, the illustrative imagery. It’s a film that exists in service of the story, and struggles to find meaning outside of that.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

But the banality of its approach almost amplifies the astonishment that comes from its tall tale; not just like unlikelihood of its first reel, but all the dark secrets, shadowy conspiracies, and unsolved mysteries that are eventually brought to light. It’s not a work of cinematic artistry, but, good lord, it’s one hell of a story.

WORKING CLASS BOY

The endless ranks of music documentaries are, largely, born out of fandom: made by people who love the acts they chronicle, with a willing audience of fans waiting to consume them. Fandom isn’t a prerequisite for viewing these docs, but it sure helps: so-so pieces of filmmaking saved from the dustbin of history by dint of just turning loose amazing music. The thornier cases — as viewer and, certainly, as critic — come when you’re not a fan of the music in question; or, even, if it openly repels you. If a bad rockumentary can be rescued by amazing music, can an interesting film be sullied by very-much-not-amazing music?

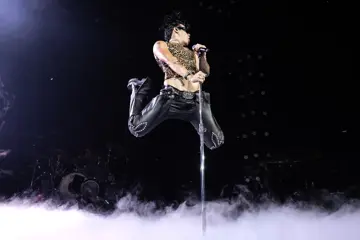

Working Class Boy is a fantastic case study of this, in many ways; the pendulum swinging wildly throughout its presentation. It’s easy to respect, admire, and be moved by the film even if you’ve never heard of Jimmy Barnes. For most of its running time, the singer stands on unadorned stage, essentially recounting his memoir: a grim struggle of survival, coming through a hard-knocks childhood, finding salvation in music, and, eventually, growing up to become someone who could, finally, break the cycles of abuse (be it of alcohol or of violence) so endemic to where he came from. But the raw story is offset by performances inserted in the narrative, all of which veer towards variety-show-soul-revue numbers, at once all-too-tasteful yet oversung, overwrought. Every time another song came on, I found my swelling heart suddenly sinking, which is never a great sign for a film.

LEAVE NO TRACE

It’s not often that a film actually gains something by being preceded by a movie of similar story and theme. If you’re watching, say, a Whitney Houston documentary after just watching a Whitney Houston documentary, it’s usually going to fail in comparison, if only for the repetition. But with Leave No Trace, comparisons to Matt Ross’s awful Captain Fantastic aid this film to no end.

Here, we get another self-sufficiency fantasy for a woods-lovin’ dad, where the prelapsarian idyll is soon ruined by the dictates of government; with the ultimate moral being the need for even an outsider to reconcile himself with society, and even an all-controlling father allowing his children the freedom to make their own decisions. This means Leave No Trace entirely resembles Captain Fantastic in premise, but is something close to its cinematic opposite: dodging all of that film’s cheap dramatisations, unearned sentiment, Sundancey crowdpleasery.

Instead, director Debra Granik — finally delivering a long, long-awaited follow-up to Winter’s Bone — authors a study of human behaviour; the contrary compulsions towards both individualism and freedom, to belonging and structure. Her key charges are Ben Foster and Thomasin McKenzie, father and daughter, whose sense of belonging is to themselves, not any place. He’s a military vet, she’s quiet as a mouse; but, at first, we know little of either, there's no moments of grandstanding characterisation. We meet them when they’re living a self-contained, self-sufficient, subsistent existence in a national park in Oregon. This is, of course, illegal, and soon enough their bubble is burst.

The story that unfolds, in its wake, is about trying to find a place in the world, rather than running away from it. Granik’s direction is unobtrusive, often observational; favouring a sense of verite in drama, and calm in her compositions. Her film neither romanticises nor criticises the chosen life of its characters, instead seeking only to depict — and understand — the complexity of people.

MIRAI

Mamoru Hosoda’s fifth film as writer/director finds the anime auteur playing the hits: it's a tale of a boy finding a magical portal in his garden filled with all the themes/tics/loves familiar to fans of the director. There’s childhood fantasy, parental sacrifice, sibling dynamics, time travel, another realm existing alongside our own, a marriage of the quotidian and the magical. The promo poster for Mirai wears this on its sleeve. Its image of a schoolgirl in flight is a direct hat-tip to 2006’s The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, with the background occupied by the director’s favourite animated obsession: billowing cloud formations in front of a bright blue sky.

It’s a film attempting to see the world through the eyes of a four-year-old boy, and, in such, a different kind of coming-of-age movie: a toddler discovering not just their own identity, but theory of mind. Mirai is named after the younger sister who’s brought home from the hospital in its opening act. Kun, our four-year-old lead, acts as his age suggests: a mixture of love, wonder, jealously, territoriality. Hosoda clearly is telling a story steeped in his own experiences of parenthood with animation a form to explore toddlerhood in a way that traditional narrative — which would require quite a toddler thespian — just can’t.

The magical portal that opens up is a way of teaching Kun about his family: travelling on a journey through time and space, he meets his grandfather as a young man, his mother as a child, his dog as a human, and, most notably, his sister — and, then, himself — as a teenager. Hosoda uses these visits to alternate realms and timelines to get pleasingly psychedelic. And these animated flights-of-fantasy bring with them unexpected profundity: these fantastical realms not taking our pint-sized anti-hero away from reality, but deepening his understanding of it; and deepening the grand familial emotions at play, both in story and for audience.

THE INSULT

“Old Civil War wounds” are opened in this Lebanese courtroom drama, in which a trial between two men from opposite sides of the political divide — a conservative Lebanese Christian and a Palestinian refugee — symbolise a greater issue. This is a noble notion for a drama, and, at its best, Ziad Doueiri’s movie manages to make its micro drama pleasingly macro. At it worst — which is, sadly, often — The Insult plays as thuddingly obvious and overly simplistic.

Its central argument — which spirals into a court-case — is, indeed, centred around an insult. When an immigrant contractor, Yasser (Kamel El Basha), dares fix the gutter of the defiant, sneering Tony (Adel Karam), his work gets vindictively smashed, in an act suggesting greater bigotry. When Yasser calls him a “fucking prick”, it’s an accurate character assessment: Tony a conservative, a nationalist, a racist, a terrible husband to a wife (Rita Hayek) that surely could do better. If he was penned as a satirical portrait of a caricaturish villain, that’d be one thing; instead, you get the sense this is supposed to be some kind of identifiable everyman.

So, what we get is a showdown between two prideful, stubborn men, who refuse to budge from their position: one demanding an apology, the other refusing to give it. As endless attempts at mediation come undone by intractable masculinity, the evocation of political discourse — the posturing, machismo, and illogical oppositionism — is strong. Yet, the longer The Insult goes, the more blatant all this becomes; the syrupy melodrama suggesting a filmmaker who assumes his audience isn’t bright, and thus delivers his points and symbols with sledgehammer subtlety. All the flick’s weighty themes, in the end, make only for leaden filmmaking.