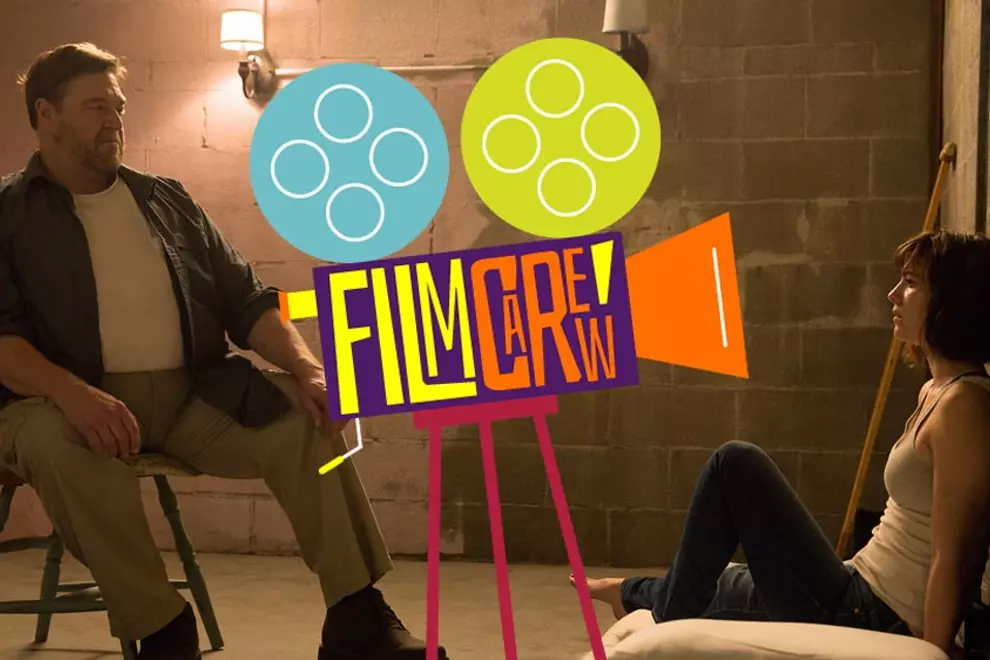

10 cloverfield lane

From the moment Mary Elizabeth Winstead wakes up shackled to the wall in some creepy basement at the opening of 10 Cloverfield Lane, we want her to survive. Because we are human creatures capable of empathy, even for characters played by actors. Because she is really good-looking. Because she was —and is, still, in our hearts— Ramona Flowers, this one girl. Because she is the heroine of the movie, the film’s emotional ‘in’. And, sure enough, as heroine the movie, survive she must, and survive she does.

But was it, exactly, that she’s surviving? Is she surviving what’s out there? Or what’s in here? Is John Goodman, her super-creepy quasi-captor, the man who —as he’s happy to keep claiming— saved her life? Or is he out to take it? What’s more dangerous, the supposed radiation that’s contaminated the planet above? Or life with Goodman in his below-ground bomb shelter?

So goes 10 Cloverfield Lane, a film that tilts between a apocalyptic survival-thriller and held-hostage survival-horror; with Winstead its heroine, Goodman its likely villain, but no simple reading to be trusted. They’ve found themselves locked-up together in Goodman’s doomsday bunker, and so has John Gallagher, Jr. the unexpected third-party that serves as the story’s hinge. Just as he’s unsure who is the most paranoid party, Winstead or Goodman, so, too, does the film keep you guessing. Not just at what looms outside its subterranean walls, but what its intentions are, what its very genre is.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Given that it’s a ‘spiritual successor’ to 2008’s found-footage monster-movie Cloverfield (or, in producer J.J. Abrams’ words, a “blood relative”), that brand association may lead some viewers to assume they know more than the characters on screen. But the assumption is bunk, because the connection to the original is so tenuous: this is a different film in a different time in a different place in a different style in a different genre. Hell, in two different genres, at least.

As the script —largely written by Damien Chazelle of jazz-movie/Whiplash fame— plays with audience perceptions, screenwriting formula, and the tropes of genre, it does so with a sly sense-of-humour. There’s great ironic use of feelgood montage and baby boomer hits: a passing-of-time sequence set to The Shondells’ I Think We’re Alone Now; a creepily-gleeful Goodman celebrating ‘teamwork’ (and, perhaps, ongoing imprisonment) by punching in The Exciters’ Tell Him on the jukebox.

And, yes, his bunker —a lair halfway between perverse fantasy of the All-American house and/or droll depiction of a slightly-too-‘homey’ B&B— has a jukebox, as well as ’80s board-games, a VHS collection filled with John Hughes teen-movies, a fishtank, food to last for years, and, oh yeah, locks on every door and a giant drum of perchloric acid that no one man can lift. There’s Martian-esque inventiveness in both Goodman’s preparations for this, and in Winstead’s attempts to regain control, to discover what’s outside, to escape.

Eventually she does, as survive she must. And what happens then takes 10 Cloverfield Lane from its self-contained, fairly-low-stakes, low-budget genre-poking, out into a whole other world, essentially a whole other movie; its final-reel a profound act of reinvention that makes all that’s preceded it seem ever-more-playful in hindsight.