crazy rich asians

Crazy Rich Asians is a triumph of Hollywood screen representation, but not of cinema. It’s the first American big-studio film to feature a predominantly-Asian cast since The Joy Luck Club in 1993, a fact whose statistical improbability suggests long-running institutional racism. Call it the soft —or not-so-soft— bigotry of the studio exec, hiding behind the self-serving logic that such prejudice is really all about what audiences want to see. The wild insta-success of Crazy Rich Asians is a glad example of old, troublesome box office myths being exploded, never to return. The film’s a sure hit, and, at least for the moment, a cultural touchstone. But is it actually any good?

Um, no. It comes peddling rom-com clichés, two-dimensional caricatures, and uncritical wealth-porn. Its story is part meet-the-parents sitcom, part fairytale fantasy, where a New Yorker gal (Constance Wu) discovers that her hot, oft-shirtless, boyfriend (Henry Golding) is the scion of a Singaporean empire. Before the opening reel’s out, she’s whisked away to a decadent world of luxury and privilege and dispiriting gender-norms, where she also has to deal with disapproving relatives/rivals hoping to run her out of town.

There’s a forbidding, nightmarish mother-in-law figure (Michelle Yeoh). There’s a wacky best friend offering sassy relationship advice (Awkwafina). There’s plentiful zany comic-relief, including a run of male buffoons (Ken Jeong, Jimmy O. Yang, Calvin Wong). There’s a trying-on-outfits-before-going-to-the-party montage. There’s telegraphed dramatic developments, a big falling out 15 minutes from the end, and, finally, a rush-to-the-airport, grand-public-declaration finale. In the sad-times montage that comes with that big falling out, our heroine spends days lying in bed, unmoving; the ultimate luxurious privilege being able to endlessly wallow in your sadness, rather than needing to just go to work or get the kids off to bed.

It’s the kind of film where the monetary value of real estate, jewellery, and event weddings is spoken aloud with awed dollar-signs attached. When we arrive at the grand family mansion of our boyfriend’s fam for a veritable girl-goes-to-the-ball moment, we’re told the property-value whilst the camera gazes upon the mansion in Spielbergian wonder, sweeping overhead and sweeping strings summoning a sense of ill-placed awe.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

It’s as if all this ultra-moneyed grotesquerie doesn’t make Crazy Rich Asians a 1%er horror-show, but some dream come true. Who hasn’t wanted to live in a house where they’re tended to by an army of unspeaking, ever-scurrying servants? Buy/receive jewellery whose colossal stones are etched with the untold suffering of mine-workers a world away? Or blow $40mil on their ‘dream’ wedding?

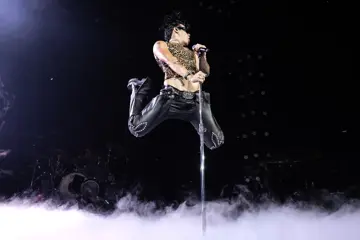

The overall pictorial air has the artistry of reality-television: chronicling the lifestyles of the rich and famous, with plentiful food-channel close-ups of plated dishes —from Hawker street-food to silver-service haute-cuisine prepped by the unspeaking servants— and second-unit city-scapes that look as if they were filmed by the Singapore Tourism Board. Director John M. Chu comes to Crazy Rich Asians having made two Step Up movies, two Justin Bieber movies, two revivals-of-’80s-toy-commericials (G.I. Joe: Retaliation and Jem & The Holograms), and Now You See Me 2; so, y’know, adjust your expectations of artistry accordingly.

Chu will likely be the choice, too, when the obligatory sequels —Kevin Kwan’s source-text book-series has two more instalments, China Rich Girlfriend and Rich People Problems — soon come our way. Whilst, for the moment, people are delighted by Crazy Rich Asians, by the time these subsequent flicks’ve been served up, to diminishing returns, it’s doubtful anyone’ll look back fondly on this first film.

Both when watching this flick, and thinking about it, there are moments reminiscent of and parallels to be drawn to 50 Shades Of Grey, Sex And The City, and My Big Fat Greek Wedding, all of which were huge box-office successes and cultural phenomena upon release, even being celebrated for servicing a neglected Hollywood demographic (women!). But history isn’t kind to movies celebrated, in the moment, for something other than their artistic merit. Those films are all, in hindsight, bad. Removed from its time in the sun, its watershed cultural moment, Crazy Rich Asians will be seen as the same.

the happytime murders

From Meet The Feebles to Team America: World Police to Wonder Showzen, raunchy puppets have long been a failsafe comic staple. Forever associated with wholesome children’s entertainments, there’s simple, subversive pleasure in seeing felt creatures or wooden marionettes enacting the foul-mouthed, lascivious desires that were assumedly lurking beneath their friendly façades the whole time. The Happytime Murders, however, is the place where this comic trope comes to die.

Here, there’s puppets as standover thugs, degenerates, pornographers, sex workers, sordid celebrities. They smoke, swear, fight, fuck, do drugs. But it’s never funny; there no comic invention beyond the simple adolescent thrill of getting these felt creations to do naughty things. The flick’s showstopping gag —an explosion of silly-string as puppet ejaculate— is in the trailer. It doesn’t get any ‘funnier’ than that.

The film is, beyond its bawdy puppet-premise, essentially a riff on old detective tropes: the disgraced LA cop turned lowlife flatfoot —though, this time, he’s a puppet!— lured into a dangerous this-time-it’s-personal case by a femme fatale. There’s a livewire partner (Melissa McCarthy, sadly not live enough), an Angry Black Captain, the obligatory moment where our cops’re kicked off the case and go rogue, and a resolution where someone gets shot. With Maya Rudolph one of the unfortunate humans herein, the best parts of watching The Happytime Murders came when I was remembering scenes from Inherent Vice.

Adding an extra layer of disappointment and dissatisfaction is the failure of the film to grapple with the race-relations parable that’s tentatively hinted at, but completely shied away from, in the text. Here, puppets are second-class citizens, subject to epithets, police harassment, and systemic inequality. But writer Todd Berger has no interest in taking this idea, well, anywhere; let alone turning the film into an incisive critique of contemporary America. Instead, he delights in the cheap and easy, less time spent on social criticism than spent on the ‘hilarity’ of a drug-addicted puppet offering 50¢ fellatio.

mile 22

The Good: Mile 22 moves super-fast, compressing its global-political paramilitary-task-force action-move into 90 brisk, barrelling minutes. The Bad: um, maybe it could’ve used some extra time to give the audience better writing, characters, and, most importantly, action sequences. “I suggest you chop-chop,” barks Lauren Cohan, herein; essentially intoning the movie’s MO, which appears to be ‘hurtle by so fast people won’t notice the idiocy at play’.

Mile 22 marks the latest dickswinging collaboration for Peter Berg and Mark Wahlberg. But, after the run of Lone Survivor, Deepwater Horizon, and Patriots Day, this time it isn’t an action-movie retelling of recent news-coverage history. Instead, it’s a most unreal film, starting with the fact that it takes place in the fictitious “Indocarr City, South-East Asia”, an intertitle sure to bring loud guffaws from an audience. When one of the fast-talking, wise-cracking, no-nonsense, go-getting agents talks of “the country” falling to pieces, it leads to this unfortunate exchange: “Which country?” – “The country you’re currently sitting in.”

The country, here, is the non-place of the internationalist action-movie; a vaguely-foreign backdrop for Americans to shoot people in front of. Though set in “South-East Asia”, it was shot in Bogotá, literally on the other side of the planet to its supposed locale. Here, Wahlberg leads a crack team charged with getting informer/double-agent/triple-agent Iko Uwais the hell out of Dodge/Indocarr. There’s scenes where Uwais inventively beats people down, but mostly there’s endless gunfire, explosions, and so much ultra-violent death that it becomes, somehow, banal. Throughout, Wahlberg serves as the film’s voice: he talks really fast, babbling ‘cool’ phrases and macho posturings, but not much of what he says actually makes sense.

And so goes the whole magilla: Mile 22 is largely incoherent. Especially the action sequences, in which countless shots are hatcheted-up into tiny pieces, thrown together in pure visual cacophony. If you were recently impressed with the control and command of the old-fashioned action sequences in Mission: Impossible – Fallout, consider Mile 22 its stylistic opposite.