On the Gold Coast, in a dim but warm, ambient studio tucked away in a bustling industrial area or within his converted mixing room at home that doesn’t even hint at its global reach, is where you’ll usually find Forrester Savell putting the finishing touches on yet another – and likely genre-defining – album release.

The producer, sound engineer, master and, more often than lately, mixer is usually alone, and himself quiet and meditative, while he works away behind his gadget-filled desks on releases that are usually sonically “a lot” – but his judgmental cat may wander through to cast a critical ear on whatever music has landed in his lap on any given week.

“The music industry is funny like that, because you're interacting with so many different people from so many different generations,” Savell explains. “And especially the work that I do nowadays, because I'm doing a lot more mixing from home – so you're not really having the face-to-face interactions with people day to day.

“So it's hard to sort of gauge the time outside.”

Clearly the time has slipped by rather quickly in Savell’s current setting – this year he marks 26 years of music production and polishing, most of them seemingly spent invisible to us listeners but very much a beating heart during the times when artists work directly alongside him, shaping inimitable records from behind the scenes.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

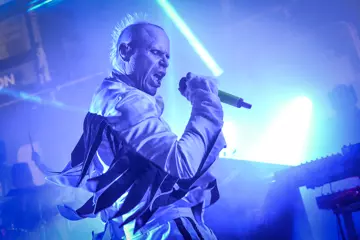

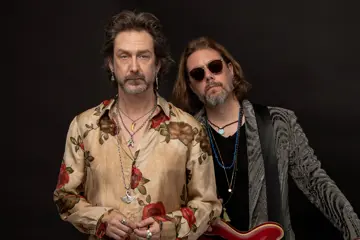

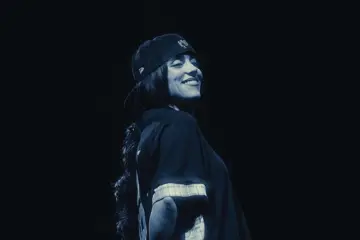

A go-to name for heavy bands from Karnivool to Cog, Dead Letter Circus, Animals As Leaders, I Built The Sky, Sunk Loto, The Butterfly Effect – and even some vibrant pop for Kate Miller-Heidke, Lastlings, and more – Savell has built his craft and reputation around mixing structurally complex compositions with bands who either fall into or either side of chaos or organised.

“It was once I came back from working in the United States years ago and did Karnivool’s first album Themata, which was a huge success for them – that’s when it was like ‘maybe I do actually know what I'm doing’,” he laughs.

The quarter-century milestone itself snuck up on him. His first paid recording happened in 2000, fresh out of the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA), when he tracked Karnivool’s first EP. As far as first wins under the belt, that’s not a bad one for a freshman – but despite being the name a lot of heavy bands turn to, it hasn’t pigeon-holed him.

“There's great music everywhere,” he explains. “If I was to play all the different songs I've mixed in the last, like, couple of months, it's a pretty eclectic collection of music.

“I think all the relatively successful stuff has probably been more on the heavier genres for me, but I enjoy working on different styles and music in different genres. Doing something you're not quite accustomed to throws little challenges that make your day interesting.”

But Savell didn’t start out as a prodigy kid tinkering with analogue recording gear. Growing up in Western Australia, music-making arrived late for him and imperfectly. He quit formal lessons early – a regret that lingers – then forced his parents to buy him a drum kit. Drumming was fun, but isolating.

“You couldn’t really make music on your own with drums,” he laughs.

He knew early on he “wasn’t a great muso”. But what he did have was curiosity and a pure, genuine, innate love of music and sound.

A guitar followed, then a cheap amp, then hours spent hacking away and mucking around with early computer programs – tracker software on prehistoric versions of Windows, sampling single notes and sequencing them into something resembling songs.

It was basic, but it unlocked something deeper: the technical side of music.

“In terms of inspiration, the guys that I think stood out for me at that time were Alan Moulder, Nigel Godrich, and Andy Wallace,” he says. “So basically, any cool band from the ‘90s – like Nirvana, Rage Against The Machine, System Of A Down, Radiohead, The Smashing Pumpkins, Nine Inch Nails – these guys had their stamp on it.

“The production of the music is actually part of the artistry and part of the song, as much as the song itself. So that was what I was really drawn to, you know, those sorts of producers where the sonics themselves were as much a role in in the result as the actual music.”

That fresh focus on making the magic behind the music carried him from his studies at WAAPA – where he took everything he could from it – jazz concerts, musicals, live sound, then quietly hijacked the studio whenever possible, dragging in willing local bands, like young Karnivool – while mixing front of house at major venues, learning live sound on the fly, and focused relentlessly on recording.

“That was it,” he says. “I wanted to be in the studio, recording artists.”

When he graduated in 2000, he packed up and moved to Melbourne and paid for his space at the coveted Sing Sing Recording Studios before another relocation, and this time a more permanent one, to the Gold Coast.

Here, he enjoyed less costly overheads by working out of Matt Bartlem’s Loose Stones studio and eventually his home set-ups, with some trade-offs but also some foresight into where the recording technology and capability was headed.

“That’s where I work with The Butterfly Effect and the Dead Letter Circus boys on their albums at that studio.

“When I moved up here, it was great, you know, lots of camaraderie, lots of ping pong, going out for lunches – but the productivity was quite low! Sound engineering, and especially mixing, you've really got to get into a bit of a flow-state to get things done.

“And it's not conducive to that when you've got lots of people poking their head in the door and wanting to have a chat, fun though it was.”

So now, as the technology has caught up to allow artists to ultimately do all the recording themselves, Savell saw the writing on the wall to mostly focus on the mixing side of things and create in the new world and workspace he had now comfortably set up – perfect for “a self-acknowledged introvert”.

He’ll still get out and record for weeks and months at time with the bands he knows and loves, but largely, it has made more economic sense for him to be not burning the artists’ budget in the studio when the now-functioning internet and file sharing allows him to do it largely from the comfort of his home or nearby studio.

“Kevin Parker is a great example of where you can do everything on your own, and it sounds amazing,” he explains. “So there's always outliers like that who are freakishly talented and can do the whole thing, but for most artists it’s just too many, too many hats you have to wear.

“The other side of things is that producing can be as much about psychology as it is sound. Different personalities in the room, five opinions pulling in different directions.

“The job is sometimes about mediation — validating ideas, defusing tension, keeping momentum, so that you’re not burning studio time,” he adds. “No one teaches you that part of the job!”

The next 25 years ahead for Savell look like they’ll continue to resemble where it all began: a quiet bedroom studio, a producer behind a desk, shaping records heard around the world.

He’s got plenty to keep him busy in the immediate future – Karnivool’s fourth and long-awaited album is due out next month, 12 Foot Ninja are getting his deft hands to polish up their latest, there’s even some film scores getting his expert mix.

Savell is still listening, still learning, still working in solitude, and somehow more connected than ever.

“If I'm saying yes to it, I'll put my heart and soul into it,” he says. “I’m always working on new and different things, with different artists every day from around the world or in some studio with them.

“That's what I’ll always love about it.”

This piece of content has been assisted by the Australian Government through Music Australia and Creative Australia, its arts funding and advisory body