Rosaline lends its voice to Rosaline, the oft-forgotten party to Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers. First mentioned by Benvolio to Romeo as "Rosaline whom thou so lovest", by Act II, Romeo has scorned her: "I have forgot that name, and that name's woe."

The collective consciousness might remember Romeo’s story as a shining example of honourable (if not imperfect and outrageous) pursuit of ‘true love’. Joanna Erskine’s script sees his behaviour more alike to Hamlet’s mistreatment of Ophelia - "I loved you not" - or as we are a modern audience, Romeo the fuckboi. Wanting sex, he turns from Rosaline because she isn’t ready. Is it because he is human — fickle and fallible? Or is Romeo a bit of a crappy man?

Erskine’s script is a joyful exercise in storytelling. It executes a clear feminist revision of the classic play, and generates an allegory of otherness and the persistent sexualisation of young women. Most exciting (and excruciating) is the slow reveal that for this young woman, there seems no safe haven in men who are supposedly able to fill the roles of love, friendship, service, or paternal guide. Erskine’s experience in writing for young audiences sings here, distilling complex issues into more easily recognisable character arcs and beats. However, some moments that might facilitate a greater sense of pathos to really find the humanity of the stage’s characters can be lost to the allegory. That being said, a moment where Rosaline watches a recording of Romeo meeting Juliet, and re-watches and re-watches, is heartbreaking.

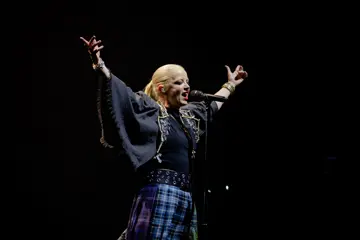

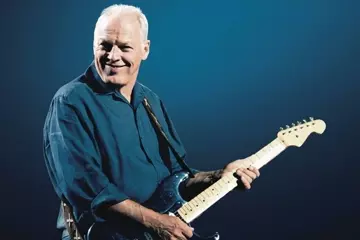

Sophie Kelly’s direction is best expounded in her casting and in her actors’ performances. Aanisa Vylet as Rosaline fixates us. She moves through coyness, sensitivity, childish trust, and confident ferocity with unrelenting deftness. The lights go down with us wanting to watch what she does next, and follow her story as far as we can. Alex Beauman’s Romeo is a hateable character, and his smarmy smile and callous manipulation (direct or indirect) of Rosaline is carried with the blindness we see in young men all the time. This is an actor who’s dug deep into encultured issues of heterosexual masculinity with empathy. Similarly, Jeremi Campese who plays Rosaline’s servant Peter, successfully captures the ‘nice guy’ trope, coming across as so believably supportive before a sense of entitlement transforms the audience’s sympathies towards him. David Lynch gives a powerful and sensitive rendition of Friar. A more classical player than the others, he brings a sense of worldliness to the show, which heightens his downfall when Rosaline calls out his fatal flaw.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

This new script is an interesting and pretty masterfully crafted story that offers an alternative perspective on a classic. While some of the human element struggles to find room to breathe comfortably, the commentary and process are fully redeeming and this is a show you should be lucky to see on its first run.