Austin Mackay

Austin MackayAustralian musicians, already seeing filing fees for working visas in the US increased by up to 260 per cent in recent years, now face claims that they may face heightened harassment at airports.

In Trump’s America, some international acts are claiming to have been profiled, antagonised, and refused entry over their lyrics, sexuality, politics and unfavourable social media posts about the current Administration.

Those typically detained can, anecdotally, according to reports, be held in a holding room for up to 24 hours, handcuffed and refused sleep.

As a result, dozens of musicians from around the globe have opted to bypass America on world tours rather than spend up to $10,000 on getting US working visas they can’t use.

Earlier this month, foremost New York City-based Immigration attorneys Matthew Covey and Will Spitz reassured Australians during a Sounds Australia/Creative Australia webinar that there were no signs so far of any aggressive targeting of Aussies.

But they agreed there are more inquiries at airports—something that began during previous administrations—and touring musicians need to get proper advice from lawyers and agents.

“We do advise more caution because there’s more scrutiny, paperwork be double-checked, that invitation letters to events are water-tight, and be careful about what is posted on social media,” said Covey.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Under previous Administrations, the number of pages of proof and other documents required for an application has climbed from 30 to the current 300 to 500.

Pollstar verified in recent months that four bands faced visa hurdles, with three deported at the airport.

Regional Mexican band Los Alegres del Barranco got banned after footage of home shows surfaced where they projected on screen an image of a cartel leader, and hence were seen by Immigration as glorifying” a “drug kingpin.”

The magazine related how Mexican superstars such as Peso Pluma and Natanael Cano tap into the narcocorridos genre, which, like hip hop, punk, folk or blues, can champion outlaws.

Veteran punk band, The UK Subs, who were stopped in March, believe they were targeted because of their criticisms of the Trump Administration.

Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau responded to the Los Alegres del Barranco incident: “I’m a firm believer in freedom of expression, but that doesn’t mean expression should be free of consequences.

“In the Trump Administration, we take seriously our responsibility over foreigners’ access to our country. The last thing we need is a welcome mat for people who extol criminals and terrorists.”

Australian acts with trans members may well worry after Canadian singer-songwriter Bells Larsen pulled his tour. He was planning to promote an album that chronicled his transition, and had changed the Gender section on his passport.

However, this year, policies were updated to recognise only two sexes—male and female—at birth.

The government agency that would have adjudicated his visa petition is U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The agency that decides whether to admit a person to the US is Customs and Border Protection. Both fall under the Department of Homeland Security.

Performers of the Muslim faith are also reportedly having second thoughts. US-based Latino music festivals see their future as dicey as foreign headliners face lengthy visa delays or unexpected bans.

In April, the superstar Neil Young posted on his website, “When I go to play music in Europe (in June), if I talk about Donald J. Trump, I may be one of those returning to America who is barred or put in jail to sleep on a cement floor with an aluminium blanket.”

Born in Canada, Young moved Stateside in the ‘60s for an illustrious solo career and stints with Buffalo Springfield and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. In January 2020, he got American citizenship and relocated back to Canada.

Allistair Elliott, Vice President of the American Federation of Musicians, said, “Under the Trump administration, with different policy changes and directives, I think it's fair to say that some individual immigration officers may take liberties with the latitude that they have.”

Tough

US Immigration officials, like many around the world, have always been tough on foreign musicians.

Australian artists and music executives have been falling foul of visa issues on arriving temporarily in America for decades.

Sometimes, the paperwork was wrong, the traveller might have blurted out the wrong thing, or an Immigration officer was being pedantic.

For years, first-time delegates to South By Southwest (SXSW) in Texas were pre-warned in Australia about the repercussions of breaching US laws.

They were told about the Australian manager of an act growing an audience Stateside who couldn’t boost it on the ground as he was banned from ever entering. He had overstayed his holiday visa as a teenager.

Much-travelled media identities have faced deportation because one airport officer deemed their work for Australian companies to be taking work away from American media.

One repeated example was the band that came to the US for contract negotiations with their record label, for which they didn’t need a visa. After clearing customs and while waiting at baggage collection, a long-haired man sporting a band T-shirt approached them.

He excitedly told them he was a huge fan and might let them sneak in some shows while in town (for which they didn’t have a visa). They were sussed enough to insist there were no plans. The “fan” wished them well… and disappeared into the Immigration Room, where he worked.

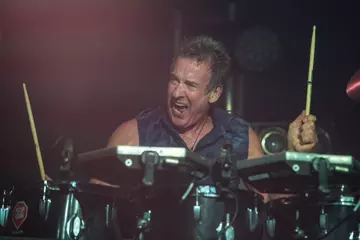

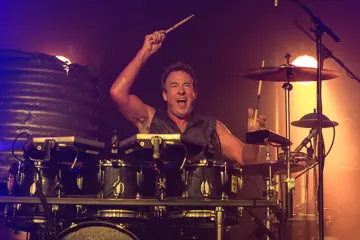

TheMusic.com.au has reported that Newcastle-based country act Austin Mackay recently encountered visa issues when arriving at Los Angeles International Airport to play Fan Fair X at CMA Fest in Nashville.

Rather than being able to lift his profile at the annual country music love-in (last year, CMA drew 90,000 attendees), Mackay never got out of the airport.

He was detained for 16 hours and sent back to Australia. All he could do was share on social media the live set he was planning for Nashville. Mackay believed he had “the correct visa and all the official invitations to perform.”

Unforeseeable

In their webinar, Covey stressed the Australian creative community needed to be aware of “unforeseeable obstacles popping up every week… fees are increasing (and) the delays due to stringent border checks has raised concerns.”

Covey is a founding partner of CoveyLaw, which handles hundreds of artist visa petitions a year and has worked for ten years with Sounds Australia.

A one-time rock musician and manager, he is also the Executive Director of Tamizdat, an NGO committed to global mobility of artists and advocacy of visa issues, which provides advice.

Will Spitz leads the firm’s performing arts division and is in charge of its visa applications.

Australian musicians on tour come under the P and O work visas. It allows them to go in temporarily to perform (both free and paid), record music, shoot a video, attend a conference or accept an award, and attend business meetings and auditions.

These were created in the late 1980s to protect US labour interests, which explains the close scrutiny.

The P visas are for athletes, entertainers, artists, and “their essential support personnel” and are valid for a year.

The longer-term O visas for three years are for those with “extraordinary ability” in the arts, sciences, education, business, and athletics. Filing fees for both are $1,615.

But these one-year and three-year durations are not automatic. Artists must show that they'll have US work spanning the full intended visa period.

The P filing fee is $1615, and the O filing fee is $1655 when the US entity filing the petition (the "petitioner") is a for-profit entity with more than 25 full-time employees. The fees are lower for smaller businesses and nonprofits.

A single application covers 25 people. This works for a band but not an orchestra or ballet company, which has to pay for multiple performers.

Due to greater official inquiries, processing can sometimes blow out to six months, which is useless given the tight schedules musicians work at.

Australian musicians are encouraged by their Immigration attorneys to pay an extra $2,805 for the Premium Processing Service, which guarantees a processing time of 15 business days.

No Visa

Covey and Spitz advised that, under certain non-performance reasons, a creative could enter America without needing a working visa.

“You can come for a meeting, you can come to sign a contract, you can come for a conference, you can even come to speak at a conference as long as you’re not getting paid for it,” Covey said.

“If you’re a visual artist and you have an exhibition that is opening in the US, you can come for the opening and probably even speak at the opening, again as long as you’re not paid for speaking.”

You don't need a visa for an event that is free for the public and which is paid for by the Australian Government. The Aussie BBQ falls into this category. Performing at a university could be exempt.

“But never assume the exception applies. Always get advice about the specifics about the event.”

Covey added that even if the events are exempt, still prepare for it. “Have a proper invitation so when (the act) arrive they can articulate to officers at the airport why it is they don’t have an employment visa.”

The thorniest exemption is “event-facing”. It does not depend on the law but works on practice. It means that the audience is there to watch an audition rather than be entertained.

The US Government accepts, in principle, South By Southwest as a visa-free event. But for similar but lesser-known events? That’s up to the Immigration officer on duty at the airport to decide, “Yeah, I can see that,” or “No, it’s really a music festival, you don’t have the right visa, and we’re sending you home.”

The problem begins for Australian acts when they play SXSW, but sneakily put in a few club shows elsewhere before boarding the flight home.

They figure wrongly that because they aren’t getting paid at these extra shows or losing money or it’s a charity gig, that it’s visa-free. Free or not, it is regarded as employment.

More likely, when the band arrives for SXSW, the Immigration officer may Google their website at the airport, and find those extra shows.

As these officials are protecting American labour interests, foreign musicians playing a free show are irritating to Immigration officials because not only is it considered taking a gig away from an American, but also devalues their worth by not accepting payment.

The other mistake by Australian acts is that, once at home, they babble about these unofficial gigs on social media. When they do return Stateside a few years later, those posts remain a footprint.

An artist manager joining a tour doesn’t need a working visa. Their role is considered incidental to the running of a tour because they’ll be holding business meetings.

But the tour manager is regarded as essential. The grey area comes with entourages saving money by pulling double duties, and the artist manager takes on some tour manager work.

Covey and Spitz noted that there is no solid rule about songwriting.

If a writer takes in a ukulele to hang out with a friend on his beachfront porch to casually knock off some songs, it’s “probably” fine.

But if they have a US deal with a publisher and are hired to write for a superstar’s record, that’s “work.”

Songwriting camps are case-by-case risks. But generally, if organisers have plans on who attendees write with, and there’s a promise that the resulting songs could be recorded, that’s “work.”

Underscored in the webinar was the absolute need to remain honest with Immigration officials when questioned, especially about a criminal past. The shoplifting charge an Australian got as a 15-year-old might have been expunged from Australian police records and no longer an issue at home.

But US authorities have access to a wide range of global databases. “What you are covering up is not as bad as what can get you banned for life,” they said.

Matthew Covey is at matthew@covey.law, Will Spitz is at will@covey.law, and Tamizdat’s website is https://tamizdat.org/.