All Riverine cared about was his music, so when a PR (or public relations) representative emailed him, asking him for money in exchange for his big break, it was a no brainer.

And just like that, $800 was gone – and so was his PR guy. “We gave him our last dollars, and as soon as the money went, no contact,” Riverine says.

Now, it’s not like he was a naive victim of a low-level scam. He did his research. The publicist had big clients. He had a website. He had a PR company. He had a good reputation. Yet Riverine still got scammed.

So what’s the deal? And how do you avoid getting scammed in an industry that’s so damn good at it?

Sketchy PR

Look, Riverine isn’t the only one in the industry dealing with people like this. He’s met multiple artists who have “all had horror stories” of alleged PR reps who have ripped them off.

“It’s really hard, because PR is something [where] there is no guarantee of delivery,” he says. “Anyone can say they’ve got a network and promise that they’ll send an email, but they can’t ever guarantee you a result. So it’s super dicey.”

I’m not saying PR in general is a scam. On the contrary, I think good PR can really elevate your career, if you’re in the right space and time for it. But artists do have to be careful.

As swindled rapper MUDRAT puts it, “You're competing against an industry that is very well versed in taking advantage of you.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

He wasted 18 months and $8,000 on a publicist who did nothing. “There's no accountability in terms of, ‘Here’s who I hit up, here's how I did it, here's what they said.’ So you have no idea what he’s actually doing,” MUDRAT says.

The Melbourne rapper says his publicist knew exactly how to lean into his insecurities, pushing MUDRAT just enough that he would feel too uneasy within his career to hire another publicist. “I wish I had the self-worth to recognise what was going on earlier,” he says.

This practice is common for underhanded PR reps: butter the client up, make them believe you’ll take them far, do absolutely nothing for their career, tell them it’s their fault… and then leave, money in hand.

Fellow rapper and co-founder of AUD’$, Matthew Craig, has seen his fair share of disheartened musicians post-scam. “Artists stop creating because of this shit,” he says. “Artists spend money, then don’t get the success they want, then they’re broke and disenfranchised and believe the whole thing is a scam.”

The “whole thing” isn’t a scam, though – there are just a few bad apples. There are ways to spot the good (and bad) players in the industry. SGC Media CEO Stephen Green, publisher of Purple Sneakers, has offered up a bunch of helpful questions to ask any potential PR rep you may work with in the future:

“How many clients are they working at any one time?”

“Do they like your music? Ask them why. What makes it different to the other thousand songs released this week?”

“What is the angle they’ll be pitching? If it’s that it’s a good song, that’s not PR.”

He also recommends speaking to three recent clients of your potential PR rep to get their opinions. “But more importantly, ask yourself why you need PR at all. What do you want them to achieve for you? If you don’t know, don’t hire someone. If you do know, ask how likely it is. If it’s to get five key things, why do you think they can do it better than you can?”

“If there’s no good answer to that, do it yourself.”

Payola

Now this one isn’t necessarily a scam, it’s just outright illegal. Payola, often known as “pay-for-play”, is basically a type of quid pro quo. Some outlets, be it radio, TV or even magazines, reach out to artists offering air-time or promotion in exchange for a certain amount of money. It’s essentially a form of undisclosed advertising. Fun fact: that’s illegal. So I recommend you don’t do it.

In fact, in 1970, the Australian music industry was so up in arms about the prevalence of pay-for-play schemes that commercial radio didn’t play new records for almost six months – what we now call the 1970 Radio Ban.

But payola didn’t end after that. It actually became a bigger deal – at least in America. In 2004, New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer launched a full-blown investigation into it, and found that Sony BMG Music Entertainment had been involved in several instances of “multi-faceted pay-to-play”. They were fined $10 million USD. Spitzer kept going, and in 2006, found Universal Music Group guilty of the same thing, fining them $12 million USD.

Spitzer said to NBC News at the time, “Consumers have a right not to be misled about the way in which the music they hear on the radio is selected. Pay-for-play makes a mockery of claims that only the 'best' or 'most popular' music is broadcast."

But it’s not just that payola is illegal – and a disappointing stain on the reputation of the industry. It’s also, very often, an easy way to get scammed. Scammers tend to pose as radio DJs or editors of big music magazines. They’ll reach out to you, say they love your stuff and they want to promote your work, and get you all invested. But there’s a catch: you have to be willing to pay for it.

A lot of people are willing. After all, a couple of hundred dollars for a chance at the big leagues? I’d take that. But little do they know, that play isn’t coming. That magazine feature isn’t coming. They simply got scammed.

It’s more common than you think. Countless Reddit and Quora threads can be found in just a quick Google search, with titles like “Does anyone know if this is a scam?”, “Is this a scam or legit?” and “Music press scam”. You can find countless stories of people being approached by “legitimate” DJs and writers, asking for a small fee in exchange for an opportunity of a lifetime that will never come.

There’s a very simple solution to avoiding this scam, though. If someone reaches out to you for a payola-type situation, say no. Don’t even consider it. Either you’re taking part in some pretty sketchy business that could land you in hot water, or you’re on your way to parting with a whole bunch of money. That’s a lose-lose situation if I’ve ever heard one.

Feature Fees

Another pretty common scam comes in the form of feature fees.

Normally the term “feature fee” refers to the money an artist will pay another artist to have them feature on a track – Taylor Swift, for example, was probably paid the big bucks by B.o.B for her feature on his 2012 song Both Of Us.

But I’m not talking about that. In a weird switching of roles, some artists charge others to feature on their songs, albums or mixtape – and then don’t drop them.

Imagine this: you’ve just released your first-ever track, you open your phone to check Instagram, and your idol has messaged you, saying he likes your stuff and wants to promote it. You’d be ecstatic, right?

That’s how Danny Grave$ felt when a big-time rapper reached out to him a few years back, asking if Grave$ would like to be on a mixtape the rapper would be presenting and promoting. “Send me a hard record where u just rappin that talkin that shit,” the message read. “Its gonna be on top mixtapes SoundCloud and we got support from blogs.”

At $500 USD for a slot, Grave$ took the deal. “At the time, I didn’t know anything about the music industry yet, and I just was all excited,” he says. “I was like, ‘Oh I can fork over the money easily,’ you know?”

Afterwards, Grave$ was surprised to hear the mixtape featured 50 artists – and there were four mixtapes released. “How are you gonna ever get heard in a mixtape where there’s 50 different artists with 50 different songs, and there’s three or four other mixtapes that are dropped at the same time?”

To make matters worse, the mixtape wasn’t posted on the prominent rapper’s profile – it was posted on a random SoundCloud account Grave$ had never heard of. And it was deleted within a few days. “It was up there for two, maybe three, days – and then it was off SoundCloud,” he says. “I didn’t know if it was just like temporarily down, I just didn’t have any idea. And I was like, ‘Oh, whatever, I probably got scammed.’”

When asked if he got any recognition or listeners for the mixtape, Grave$ immediately replies, “Absolutely not.”

Copping the betrayal on the chin, Grave$ just counted the situation as a lesson learned. “It is what it is, you know? It happens. That's how the music industry is,” he says. “That's just the way some people operate. Like some people live more off the music side, and some people do more like, hustling, you know what I mean? Like, you gotta do what you gotta do to get your money.”

He says he doesn’t necessarily blame the artist for his loss of money: “Maybe that wasn't their original plan, you know? And maybe it wasn't their fault it got taken off of SoundCloud, you know? So I really have no idea. But you knew what you were getting yourself into when you paid for your song to be on the mixtape.”

Grave$ always had a sneaking suspicion the opportunity might go sideways, and was prepared for a loss. Others didn’t necessarily have that foresight. “There were a lot of people that were a part of it,” he says, “and I don't know if a lot of them knew that they were being scammed – but it was a scam, you know, it was as clear as day.”

Now, no one is quite sure whether these scams are run by the actual artists, whether they’re selling their accounts to scammers, or whether they’re simply getting hacked. Either way, it’s a lot of cash for them, and a big loss for small artists.

“It was a couple hundred dollars, and between 50 people paying that much money, that's a lot of money,” Grave$ says. “I kind of figured it'd be something like this. Once I found out 49 other artists were in it and paying the same amount of money, I knew it was just for the money.”

Since then, Grave$ has seen multiple iterations of this scam. An X thread about it blew up in 2020, with many unsigned artists coming out of the woodwork to admit they too had fallen for the scheme.

Either way, I doubt you want to be out-of-pocket a couple of hundred dollars to get on a random mixtape that probably won’t get put up. So here’s how to avoid it, according to Grave$: “If you see an artist that you follow go from posting videos of [themselves] or a new music video or whatever it is, and all of a sudden it just goes to, ‘Oh, I got promotions and deals for artists’, and if you see multiple of those in a row, that's something to look out for right there.”

“The best advice I could give is, don't even message back if you think it's a scam. Stick to making your music and doing your thing, and it'll all pay off in the end.”

Hosting

Venues, look out. This one’s for you. I mean, this isn’t super common, but it’s worth keeping an eye out for.

Some venues have events where a famous person is brought in to “host” – often it’s an “official after-party” for a festival or concert, hosted by a notable artist of some kind. But what does “hosting” entail?

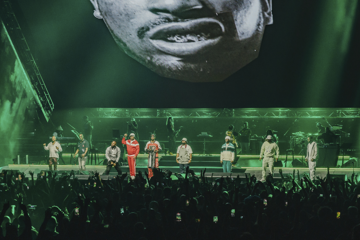

That’s the argument Drake’s lawyers had to participate in after Bearzerk Presents considered legal action against the rapper, following his infamous snub at a Melbourne after-party he was supposed to be “hosting”.

Drake’s contract with Bearzerk allegedly required him to host the official after-party at Crown’s Therapy nightclub for 60-90 minutes, following his concert earlier that night. Yet despite his contractual obligations, fans (who had paid up to $105 for entry) were disappointed to only see the rapper, who hid in the VIP section for the majority of the night, for about 90 seconds – not quite what those 500 punters paid for.

Drake didn’t face any legal repercussions (at least not any that are public knowledge), but considering how many calls for refunds Crown had to deal with, this whole incident would’ve ruffled at least a few feathers.

Now there aren’t any clear-cut ways to avoid this, but a start would be to clarify exactly what “hosting” entails. Oh, you didn’t want Drake to sit in a corner on his phone all night? You should’ve told him that!

Ticket Fraud

In case you’ve somehow missed it, the biggest and most common scam in the music industry is based around ticketing. There are so many different ticket scams around, but most revolve around you being sold a fake ticket, a non-existent ticket, a ticket with a worse view than you paid for – or even your details getting stolen by hackers while you’re in the process of buying fake (or real) tickets. Sounds fun, right?

It’s not. Isabella Brown knows that firsthand. She and two of her friends were scammed out of $1,200 when trying to buy Taylor Swift tickets. “Basically, my aunt messaged me, saying that her friend was advertising tickets on Facebook and that I should message her,” she says.

Brown had seen scams like this before, so she came prepared, messaging her aunt’s “friend” for some proof. “I asked for her to give me details of the tickets: what night, what section, and photo proof of the tickets. It seemed legit so I asked for three tickets.”

Brown wasn’t fully convinced, though, and asked if she would be able to pay for one ticket first (to see if it was valid) before paying for the other two.

Shockingly, the scammer wasn’t a fan of that idea, and refused. “I caved too quickly, thinking they would give the tickets to someone else. I sent $1,200 for three tickets – which, in hindsight, was the dumbest thing I could’ve done,” Brown says. “They then said that they would send the tickets once the money got into their account.”

They did not. Instead, Brown woke up to an unfortunate call. “The next morning, my aunt frantically called me, saying it was a scam and to call my bank, because her friend’s Facebook account had been hacked and she didn’t realise the tickets were fake. I got on to my bank about it, but by the time they tried to do anything, the money was long gone.”

Brown wasn’t the only one targeted by scammers during high ticketing periods. When Taylor Swift came to Australia earlier this year, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) warned punters of scams. But it was no use – by January 24 this year, the ACCC found that Australian consumers had already lost $135,000 to scammers, just seven months after Swift’s tickets went on sale.

If you didn’t get scammed in the great war for Swift tickets, you probably know someone who did. The most common tactic people fell for was based on social media, where real accounts were hacked, posting in community groups that they had “spare tickets” to The Eras Tour – but they didn’t. The hackers just sat and waited for hordes of desperate Swifties to flood their DMs, then “sold” the “tickets” to the highest bidder, just like Brown experienced. Within a few months, the ACCC’s Scamwatch website received 273 reports of social media scams.

Ticket fraud is rampant, but there are ways to avoid it. Here’s what the ACCC says:

“Before buying a ticket, consumers should check:

the authorised seller of tickets for the event. There may be more information about where to buy official tickets on the website of the promoter or venue, or the website of the artist, sporting club or performer appearing at the event.

if there is an official ticket reseller for the event.

that the ticket seller who comes up first in the online search results is the authorised ticket seller and not a reseller who may have paid to be at the top of the list.

when tickets officially go on sale. If tickets are on sale before the official date, they might be fake.

that they are purchasing from a secure website. Consumers should check that the web address starts with https: instead of http: and has a padlock symbol.

any restrictions on the ticket.”

Look, the music industry is a scary place. It’s very easy to be tricked or taken advantage of. But it’s also a space designed for creatives to be able to share their work and love for music – and you kind of have to be in the music industry if you want to do that.

Maybe just try not to get scammed… It’s not that hard, right?