For someone who dominated Australia’s show business in the 1950s and brought rock and roll here, Lee Gordon remains a mystery man.

It was the way he wanted it. He turned up in Australia from America with a mysterious past (three different versions), which he protected by doing no interviews. In the clubs of Sydney’s red light Kings Cross, he’d openly smoke pot even though that could have ended him in jail.

He had brash and inventive gimmicks. He had a coffin in the lounge room of his upmarket Sydney apartment. He launched Australia’s first rock and roller Johnny O’Keefe as well as strip clubs and drag shows.

Always looking for a new experience, he’d dabble in LSD which when combined with a fragile personality led to a nervous breakdown. He had mob connections, and died at 40 of a heart attack in a London hotel room in 1963 in deep debt, after fleeing Australia a year before.

He brought out 292 US acts. But his biggest disappointment was that the list did not tick off Elvis Presley, the biggest and most magnetic music star on the planet in the 1950s and 1960s.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Elvis was up for it. But his manager Colonel Tom Parker refused. No one had sussed out then that Parker was an illegal alien from Holland, and couldn’t leave the US as a result.

During Lee’s frequent visits to the States headhunting for future headliners, he had a meeting with Parker and pushed over a bag containing $100,000 ($1.3 million today) in it.

“What’s in the bag, Lee?” the Col said.

“What bag?” Gordon replied.

In a subsequent offer, the bid increased to $300,000, or $3.58 million today.

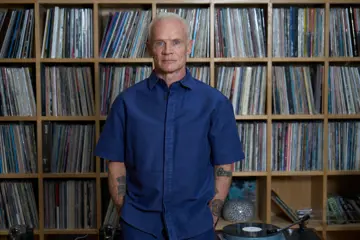

“I liked him more than I disliked him by the time I finished the book,” admits prolific NSW-based biographer Jeff Apter, of his latest book Lee Gordon Presents (How One Man Changed Australian Life Forever) (Echo Publishing).

“He had a lot of chutzpah and he was a flawed character in many ways. Fast forward to the end, and his life was pretty much a mess.

“On the flip side, he was a square peg in 1950s Australia. He was this jetsetting almost bohemian kind of character who swanned around the world much to the amazement of his colleagues whom he took on his trips with him.

“He seemed to be known everywhere. He’d turn up in the French Riviera and knew everybody. At The Sands casino in Las Vegas the owner would come out to give him chips on the house.

“But on a personal level I envied his energy, his drive, his passion. The idea that in the ‘50s he was taking gambles of hundreds of thousands of dollars – or pounds at the time – that just does my head in.”

The next generation of show biz entrepreneurs as Harry M. Miller, Michael Edgley, Michael Gudinski, Michael Chugg and Peter Rix certainly agreed that Gordon paved the way for them.

Impact

To assess Gordon’s impact, you go back to Australia in the ‘50s. It was before television. The only local promoters were boring beyond belief. The acts which came out were piano thumping Winifred Atwell and armed forces pin up Dame Vera, and locals such as radio’s Dad and Dave and comedian and vaudevillian Roy Rene.

Lee Gordon heard how Australians were starving for real talent, and brought them in after moving to Sydney on September 30, 1953.

Ten months later, his first Big Shows tour took place, with jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald, drummer-bandleader Buddy Rich and clarinettist Artie Shaw. Then came Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Bob Hope and Louis Armstrong.

Initially, acts were skeptical about travelling the very long distance to Australia, which at the time involved a 30-hour flight and at least four stops.

At the time, artists who worked in both the US and Australia had to pay double tax. That changed in 1954, making it easier for Gordon.

Rock and roll had exploded in America, and he brought out Bill Haley & The Comets (playing to 300,000), Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly, Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. Also came R&B stars such as LaVern Baker, Big Joe Turner, The Platters and Freddie Bell & The Bellboys.

That Gordon’s tours were multi-racial was significant. Australia was in the grip of the White Australia Policy and government departments and the Musicians Union maintained that policy.

No African-American artist was encouraged to come since the late ‘20s when a black jazz band was deported back to America after being found cavorting with white women in their Melbourne hotel room. Gordon changed that.

“No doubt, Lee Gordon was colour blind, he didn’t see the difference in skin colour,” Apter confirms. “To him, they were the biggest artists of their time, their colour never entered his head.

“I sense he might have got a bit of a backlash as a result. But Australians were just thrilled to have them there in person that the issue of racism was never a concern for them.”

He recalls the anecdote when Johnny O’Keefe was opening for Little Richard in Wollongong. O’Keefe’s guitarist was Indonesian-born guitarist Lou Casch (real name: Lou Nanlohy).

“The kids had no idea what Little Richard looked like. They spotted Lou and thought he was Little Richard and they chased him down the main street of Wollongong.”

Also telling of Gordon’s attitudes was the time he asked Little Richard’s guitarist to a hotel bar for a drink. He was genuinely stunned when the musician told him he would not have been allowed in the main bar in the US.

Gordon already had a taste of institutionalised racism on his first tour, when Ella Fitzgerald had to miss a couple of shows in Sydney because of an incident in Honolulu airport en route.

The legendary singer and three of her (black) entourage (but not her white manager) were kicked off First Class by a Pan Am staffer. They were not allowed to retrieve their luggage and were stranded for three days while trying to get to Sydney.

They sued Pan Am for $270,000 (today’s $3.22 million) for race discrimination. They got a “nice” settlement, according to Fitzgerald in a 1970 TV interview. Pan Am feebly called it an "honest mistake" due to a mix-up in reservations.

That 12-hour Honolulu stop over was a constant nightmare for Gordon. Gene Vincent got lost and cancelled dates. Sinatra went on a blinder and didn’t make it at all. The promoter lost £200,000, and Sinatra played a couple of shows in the US and paid him compensation.

Sinatra’s relationship with Gordon was complex. They first met in Havana in 1947 in gangster Lucky Luciano’s house… although “Ol’ Blue Eyes” insisted throughout his career he didn’t know anyone from the mob.

Frank served as best man at Lee’s wedding. But on a later tour, Sinatra insisted on being flown in a huge DC7. When Gordon wouldn’t agree straight away, Frank’s manager reportedly punched him in the head a couple of times.

Opening Acts

Another substantial impact of Gordon’s tours was that by using them as opening acts, he created careers for Australian rock and rollers as Johnny O’Keefe and Col Joye, singer songwriter Diana Trask (later the first Australian entertainer to find success in the USA) and Georgia Lee, the first indigenous female artist to record the blues.

“The competition was certainly not fierce when Gordon started,” Apter recounts. “But when he started to really make inroads, there was some lively rivalry.

“He never could work out whom, but people would post photos of half-empty venues to agents and managers of big names.

“One of a half empty Sydney stadium said, in a simple hand written note, ‘This is what Lee Gordon does to your artists’.”

As to the difference Gordon made, “It sounds dramatic to say it wouldn’t have been the scene it became. It needed someone like Lee Gordon, with international contacts and backers in the States. No one at the time had those contacts.”

But being a pioneer meant the financials were as much down as they were up.

His second tour was Johnny Ray, a singer who sang sad songs and kept bursting into tears during his show. He’d “collapse” ten times at least, each time gulping water (actually, vodka).

Lee grandly announced he was paying the American £12,000 for a week of shows. Reality set in when Ray and manager arrived in Sydney two days before, and only £100 worth of tickets were sold.

Gordon pulled off a masterstroke. He had millions of 8x8" leaflets printed (paying the designer three times the rate because it was a Sunday) promising a twofor (a free ticket for each one sold) and dropped them from planes over Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane.

The dates sold out. Ray played to 200,000 folks in Sydney alone, and he went down a storm. But because of the “twofor” offer, the tour didn’t make as much moolah as thought.

But Ray went back to the States and talked about what a hit he was in Australia, and other stars figured they should go there too.

In late tours, Gordon orchestrated fantastic press coverage for Ray, arranging for 5,000 fans to meet him at Brisbane airport, made him wear clothes that would tear away quickly when he was mobbed, and even of a love affair with a local singer although Ray was secretly queer.

For another example of his chutzpah, Apter recalls: “Gordon used Pan Am to fly his major international artists First Class. He was soon in $30,000 debt and the airline stopped credit.

“He flew to their headquarters in San Francisco and told them, ‘I owe you $30,000. My company is about to go bankrupt and can’t pay.’ They said, ‘So why are you here?’

“Lee replied, “I’ve got all these international acts coming and all I need is a dozen first class tickets. I guarantee you that they will make me money and the debt will be repaid.

“So he walked into the offices with a $30,000 debt and he walked out with a handful of First Class tickets, all done with the gift of the gab.”

Gordon jumped with trends breaking in America and introduced them to Australia. But sometimes, Apter says, he was ahead of local crowds and he could take a financial bath.

He introduced the first rollerball derby. It would be another ten years before it became huge entertainment with locals and screened on TV. Australia’s first drive-in hamburger joint – the Big Boy on Parramatta Road at Taverners Hill in Sydney's inner west – was also before its time.

Gordon opened Sydney’s first adult cabaret nightspot Lee's of Woollahra in 1959, also the first strip club in Australia and the first drag club Jewel Box Revue Club in Darlinghurst. These would only become huge multi-million dollar success stories with their later owners.

When The Beatles came to Australia in 1964, there were wild scenes. An incredible 300,000 people turned out to welcome them in Adelaide. The city’s population then was 670,000.

What would have happened if Lee Gordon had brought Elvis Presley out ten years before? “The Pelvis was in his prime. All of Australia would have wanted to turn up. There would have been unbelievable chaos!”

Jeff Apter’s Lee Gordon Presents is out now.

This piece of content has been assisted by the Australian Government through Music Australia and Creative Australia, its arts funding and advisory body