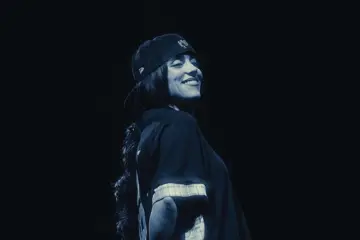

Jordan Rakei

Jordan RakeiWhile immersed in Jordan Rakei’s marvellous fifth album The Loop, this scribe experienced déjà vu. Hmmm. When was the last time I was completely floored by an entire album’s worth of jaw-dropping vocal performances? Talk about wow factor. Aha, got it! Daniel Merriweather’s extraordinary, Mark Ronson-produced Love And War album (2009).

The penny dropped as Hopes & Dreams unfurled, with Rakei’s pipes scaling peak after deliciously unexpected peak and simultaneously stopping listeners in their tracks. “I’m really happy with how it landed as this slow build,” the New Zealand-born, Brisbane-bred multi-talent admits after telling us this song evolved through “many different lifeforms”.

“It takes three-and-a-half minutes for the bass to come in, there’s no drums in the whole track – Younger Jordan would be really anxious, feeling like it’s too stale or too slow,” he muses. “But I guess it shows my maturity in production. Even just stripping things back – thinking about the voice and thinking about the story of the song, and not letting anything get in the way: that was my mission.”

When told the groovy, compositionally complex (but somehow never alienating) Everything Everything is my album highlight at present, a smile of satisfaction spreads across Rakei’s face: “Wow, nice. Yeah, I’m glad. It’s funny, ‘cause that’s one of my favourite tracks. But you’re the first person that’s mentioned that, actually, even [amongst] my friends or my band. So it’s nice to hear it’s got some love.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“But, yeah, it’s quite a fun track for me, ‘cause it’s actually really different from the rest of the album. The album’s quite soulful and that song is ticking the box of my Radiohead, [Jeff] Buckley indie influences. And I grew up on that stuff a lot, but I also grew up obviously on Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder. But that song [Everything Everything] doesn’t sound like the Marvin Gaye, D’Angelo side of me, it's more like the singer-songwriter thing or, yeah, sort of like alt-rock nearly – without the distortion. But I love it, ‘cause when I listen to that song it reminds me of the freedom that I gave myself – the creative licence – to feel confident that that song could live with the others, if you know what I mean. The old Jordan might’ve cut that, because it didn’t fit with the rest of the album. But I’m really proud to show the whole range of my influences.”

About six song demos for The Loop were already percolating when Rakei started listening to the Audiobook version of Faith, Hope And Carnage – an extended conversation between Nick Cave and The Observer journalist, Seán O’Hagan. “It was the perfect time for me to read that book,” Rakei observes. “Nick Cave’s very vulnerable in the whole book, but he actually talked about his process a lot. He said sometimes he would just sit down and say something out loud – and it has no metaphor, there's no poetry, it’s just a real statement – and that would become a lyric. I sat down after I listened to that chapter and did that a lot.

“Like in my track Hopes And Dreams – it's very straight-up, that song, there's no metaphors – it’s like: I had a child, it changed my life but I didn’t say those words. It's really simple lyrics, but I was just actually saying the words out loud and I was like, ‘Ooh, I like that,’ you know? I mean, that all came from Nick Cave’s simplistic approach, ‘cause he said in the book about, you know, stripping things back. He would write lyrics first and then work them into the song later… I love his process and the way he talks. He's so philosophical. Yeah, he’s very inspiring.”

The Loop is, unquestionably, Rakei’s most ambitious and instrumentally expansive work to date. So exactly how many musicians did he recruit for the recording sessions?

“Just the band alone was probably, like, nine of us,” Rakei reveals. “But then the orchestra was 16 string players and the horn section was six horn players and the choir was seven of us. So on a track that has all of those elements, like Friend Or Foe, I think there’s about 43 people on that track,” he laughs in disbelief. “Whereas all of my early releases are me playing all the parts, and there’s just one of me. It’s so nice to see the progression from the fun, bedroom-jam guy – when I was 12 – all the way to the really dense arrangements.”

Friend Or Foe sees Rakei trying to make peace with friendship breakups. “Everyone has friends and there are moments where they just fall away naturally, because the path of life is different and you move countries or whatever, but there’s also bad breakups of friendships as well… You realise at the end of the day that people who have had bad exits from your life have still left good things in you, there’s good things to take from [the friendship]. So coming to peace with the unresolved ending of a friendship, or just being at peace with those bad breakups, can soften your experience. ‘Cause you can harbour all this anger or resentment, but it’s just about appreciating the things they left behind in you.”

Sometimes when he’s in a reflective state, Rakei feels guilty about not making more of an effort to keep in touch with his “friendship community back in Australia”. “There’s a void there of this whole part of me that’s neglected, because of my own selfish pursuit of success or whatever it is. But the nice thing is, when I go back it’s just the same as it ever was… So I’ve been a bad friend, but it’s something I’m trying to work on,” he trails off laughing.

“This is a weird concept, maybe it’s an insecurity thing, but sometimes I wish people didn’t know my musician side and they’d sort of meet me in a pub and go, ‘Oh, that guy was a nice guy,’ or whatever. Which is all my old friends; they knew me before I was a musician. And so I miss that element of being Jordan the person rather than just Jordan the artist.”

Born in Hamilton, a small city in the Waikato region of New Zealand, Rakei’s family moved to Brisbane when he was three. When asked how lofty his ambitions were when he first started kicking out the bedroom jams as a tween, Rakei shares, “I just loved making music. From ten all the way up to 18, it was more like a hobby. I made music to make my friends laugh, or I would make comedy songs – it was just sort of a game to me. But then when I went to university and a lot of the lecturers were like, ‘Jordan, you have potential, you’ve got a great voice, these songs are so developed already,’ that’s when I was like, ‘Oh, really? I thought this was all just a hobby’.”

Rakei has been UK-based since he first travelled to London a decade ago, aged 22. “My original goal was to come over for a couple of months to work with as many people as I can, and I never went home,” Rakei offers with a chuckle. But he soon moved into “a tiny flat, really far out” (as in, a long commute to London). “I shared a bedroom with another person, it was pretty crazy,” he recalls.

“It was so surreal to me, because in Australia all of my friends – we would play basketball or we’d go to the pool or to the beach; it was less of a music thing. I had no music friends in Australia and then I come to London and everyone knows who that random artist from America in the ‘70s is and they’ve got such cool taste, and I was like, ‘This is crazy! I’m learning so much from just being around these people.

“After six weeks [in London], I was like, ‘Wow!’ I just felt like I connected to this community and the music, and I felt so inspired. I’d already played my first show, and that sold out. Whereas my show in Brisbane was just my family and friends. So I was like, ‘There’s people actually here that wanna hear my music,’ and, yeah, it’s pretty much been a natural progression ever since. I mean, I’ve just moved out of London, but I am still very much in the city and part of the scene.”

For our Zoom chat, Rakei has positioned himself in front of a window, through which we spy the rich green foliage of an English country garden. Of his current home “just out of London on the way to Oxford”, he enthuses, “I’m really grateful for being out here, ‘cause I can go on my walks – I can be in nature – but I’m only a 30-minute train from London. So it’s the perfect middle ground, at the moment.”

As Abbey Road Studios’ first-ever artist in residence, we’re tipping Rakei spends a fair bit of time on that London-bound train. “Any chance I get for a free day, I’m on the train in,” he confirms. “I’ve got this really nice routine where I catch the same train, I get a coffee and I start my day early. And then manage to do a whole day and make it home to see my baby after nursery. So it’s like a nice little nine-to-five work sorta vibe. But, yeah! I’m super-honoured to have that role. I’m now tasked with the direction of making Abbey Road youthful over the next year somehow. It’s just so humbling and amazing.”

So did Rakei find that becoming a father changed the way he feels about his own parents? “Yeah, it does,” Rakei acknowledges. “And that’s sort of what the whole album was about: parenthood… I started writing this album when my son was four months old. I was just so happy! Firstly, I was like, ‘I’ve got all these new stories to talk about and my reflections on my own parenthood and my being a child.

“I called it The Loop because I was a child, I’ve now had a child and then maybe one day my child will have a child, and we’re just on this rolling journey. I have reflected a lot about my parents and even my own upbringing and things that happened to me. You know, they were just 25 trying to blag it like I am now! No one knows the answers – we think we do, but we’re all just trying our hardest to just ensure the baby survives.

“What I like about having a child – I know my son sees me now as Jordan the person again. He knows I’m a musician, he always says, ‘Daddy singing, blah-blah-blah,’ [laughs] but it’s nice to imprint my personality on him and try and make an impact that way, as well.”

Rakei is an affable interview subject who bursts out laughing often. “My outside persona is a quiet, shy and calm sort of guy,” Rakei explains, “but when I’m at home I’m, like, running around. And sometimes I see my son doing something crazy – ‘cause my mum is like that as well, she's so full of energy – and I’m like, ‘Wow, it’s just made its way through to the next generation!’ [laughs]. It’s so sweet seeing that legacy passed on.”

Of recording The Loop, Rakei enlightens, “I was really inspired by the old-school way of making an album, like in the Motown days where they’d have a whole room of musicians. And they would just press record and you would do take after take, and then you would get in a bit of a groove. And that’s what we did: we did a whole take of it, we’d sort of talk about it, we’d do it again and then we’d be like, ‘Yeah, that’s the take. That’s gonna be the song that’s on the album’.”

Rakei also took on the role of musical director during The Loop sessions and you can hear the singers smiling while singing the gospel-infused Freedom. “We have lots of studio footage of us playing Freedom, actually, ‘cause I’m in the room directing the band – I’m sort of like [he demonstrates miming a few musical cues to invisible musicians beyond my shoulders] – and we’re all just sort of laughing. And the singers are dancing and, yeah! That was really fun to play.

“I set up all these rules of making [this album] sound acoustic and making it sound grand. I wanted to unashamedly pursue the most insanely dense music I could. So in a way I didn’t want to think, ‘Oh, an orchestra’s too over the top.’ I just wanted to go as maximalist as I could with all the arrangements; nothing was subtle, everything had to be a huge statement. And that’s massively due to Stevie [Wonder], but also even the ‘70s Motown scene; everything was so huge and orchestral in those days. So it was a throwback inspiration record to those times and his influence on me.

“I saw Stevie Wonder perform live in Boondall in Brisbane – it was amazing, ‘cause he never came to Australia. He’s my favourite artist, and I saw him in this big venue and I was like, ‘Wow, it would just be…” – and ain’t it funny, ever since then I’ve had aspirations of having a band that size. He’s got 15 people on stage: a horn section, two percussionists, drummers, singers, everything. And I was like, ‘That’s the music I would like to make, something so expansive and large,’ and it’s funny! I’ve only now, in a weird way – circling back to the album – been able to fulfil my vision. With more of a budget, I can work with an orchestra, I can work with a huge team of people and we’re able to make the album I’ve always wanted to make since I was 19.”

The Loop is out May 10 via Universal. You can pre-order it here.