Sydney Theatre Company’s adaptation of William Golding’s classic 1954 novel, Lord Of The Flies, ripples with the vitality of its young cast, most of whom make their STC debuts.

You wouldn’t know that Hollywood actor Mia Wasikowska, as the lead Ralph, makes her theatre debut here – as does Sharp Objects’ star Eliza Scanlen as one of the twins, Eric. The most engrossing figure though is Contessa Treffone as Ralph’s rival, Jack, whose descent into violence is swift and harrowing. She is loud and overbearing, physically embodying the character as he bullies the others into submission, face smeared with the blood of a hunted pig.

STC Artistic Director Kip Williams guides his cast into finding their child within – these are not adults playing caricatures of kids, instead they harness the unique vocal cadences of their younger selves. It’s a play brimming with physicality, from the running and climbing of kids stranded on an island far from home, to the fighting made real thanks to movement and fight directors Tim Dashwood and Dr Lyndall Grant. The seeming authenticity of the actors’ performances as kids also comes down to the strength of the adapted script from Nigel Williams, as well as the skill of dramaturg Eryn Jean Norvill.

The queering of the boys of the novel – women playing British private schoolboys, clad in Marg Horwell’s casual costumes – is an attempt by Williams to talk about masculinity, the way it is learned and endowed on new generations who then perform even its most toxic elements. The point doesn’t quite land, possibly because the emotional world of the play comes off as secondary to the mounting action, with less time given to an examination of gender than to ramped up anxiety. We may be watching ‘boys’ fight but that instinct for domination – and for escape – feels very human here.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

It shouldn’t feel so exciting and provocative to see a line-up of young actors so diverse and talented, but it is – here, we have genderqueer actors, differently abled actors, and actors of colour, and at no point are their identities treated as plot points. Instead the play is carried by the action, the rapid escalation of tension and fear, as characters dart across Elizabeth Gadsby’s sparse theatre stage.

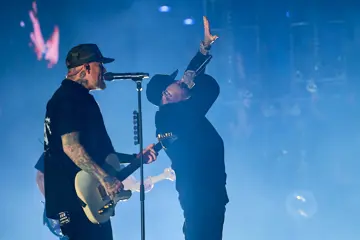

The staging is like a theatrical rehearsal room, the actors hanging from scaffolding or racing by on storage trunks. That starkness allows us to project our own meaning onto the production, our own image of what this world of escalating tribalism looks like. James Brown’s sound design adds to a feeling of malice and fear, the beat contributing to a dawning sense of dread.

As the tension climbs, the lighting from Alexander Berlage shifts with it, fluorescent tubes emerging from the dark to form a blue-lit forest through which the cast must navigate. We watch the lights cleverly change from blue to red, illustrating the feeling on that island as the impulses of Jack and his gang turn murderous. When the stage fades to black for a moment of extreme brutality, it only heightens the impact for the audience.

We’re left with the image of a society turned toxic by gang mentality and a lack of empathy, where those who seek only shelter and fire are preyed upon as weak. It’s a frightening image, made vital through its presentation in such an unadorned way, relying instead on the physical language between the impressive cast.