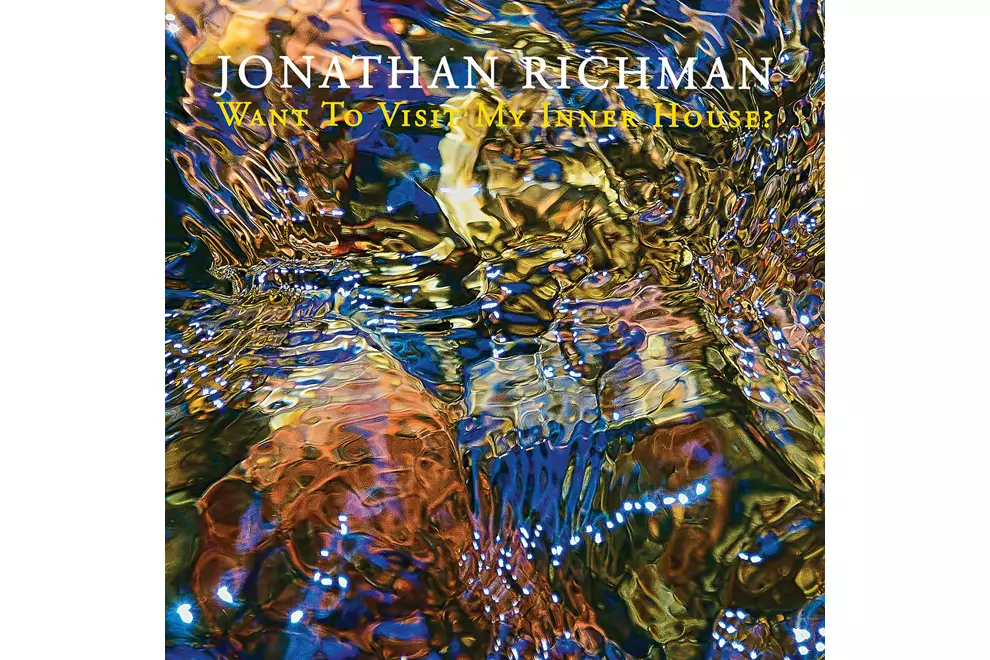

Jonathan Richman

Jonathan RichmanTrust Jonathan Richman to invite you into his inner house only to spend most of the time talking about the outside world. The seventy-year-old singer-songwriter has chiselled his own niche out of singing about beaches, bus fumes, ponds, alleyways, mowed lawns, water fountains, highways, les étoile, the lilies of the field, and discarded chewing gum wrappers – the vibrant and dilapidated beauty of the world. He’s one of the most idiosyncratic and enduring figures of rock'n'roll’s recent history. And his eighteenth studio album is, unsurprisingly, downright charming.

“Do you know anybody who loves life more than I do?” Richman sings on This Is One Sad World. “Probably no!” he concludes, and his gleefully-experimental discography attests to this. For almost fifty years now, the Massachusetts musician has been searching for sounds to express both inner and outer worlds, seeking to collapse the barrier between the two. This is, needless to say, an impossibly ambitious undertaking, but it’s one that Richman performs with humour and humility.

This particular album follows on from 2018’s SA, which found Richman collaborating with keyboardist and producer Jerry Harrison (The Modern Lovers, Talking Heads) and tamboorist Nicole Montalbano to incorporate the hypnotic, droning qualities of Indian ragas. The tambura is occasionally present at the bookends of this new record, and Harrison’s playing adds colour to the canvas of early and late album tracks, although they gradually take a backseat to Richman and drummer Tommy Larkin’s shared musical chemistry. As such, the sequencing of the record invites the listener into a stripped-back state of intimacy, culminating in Richman’s latest song of contrition, I Had To See The Harm I’d Done Before I Could Change. The additional instrumentation returns as the album closes. We visited his inner house, see?

The title of the album refers to a poem by the Indian poet Padmalochan, and Sento, Sento is also based on translated poetry by Paramahansa Yogananda. “Mother, I hear your voice in the flowers,” Richman whispers on the penultimate song. Spirituality has always been an element of his music, and his pursuit of connection expands beyond that of performer and audience, seeking communion with all things. It’s this encompassing embrace of life that renders dichotomies like inside/outside irrelevant for Richman, as the desire for closeness carries him ceaselessly forwards. “How close can I be?” he asks, “How close does it get?” No one knows for sure, but Richman helps us approach an answer, and inspires us to find out for ourselves.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter