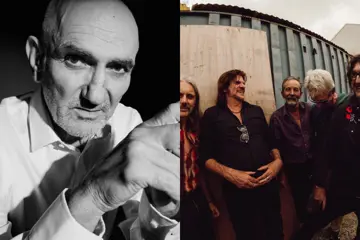

Chris Carey

Chris CareyIt likely goes without saying that anyone who considers themselves to have the finger on the pulse of the music industry – local or otherwise – needs to be thinking ahead, to be taking on board all of the info they have available to them, and to be using all insights on offer to ensure that their experience within the industry is as considered as can be.

This month, the Victorian Music Development Office (VMDO) will be helping industry insiders gain a deeper understanding of the state of the music world this month, with the launch of the inaugural Music Data And Insights Summit.

A two-day affair featuring some of the brightest minds in both local and international music, it’s an opportunity to dive deep into musical data, with keynotes, panels and presentations covering a range of topics including live music venue data, workplace skills trends, music consumer insights and analysis of the streaming economy.

Held in Naarm/Melbourne across April 28th and 29th, the event features many important figures from the world of music, though it’s hard to go past Chris Carey. A UK-based music strategist, Carey has been in the game for close to two decades now, initially venturing into the music game as part of British music copyright collective PRS For Music.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Working alongside Will Page (who would later hold the role of Chief Economist at Spotify), Carey later found himself as the Global Insight Director at EMI Music, where he noted he “transformed 14 billion rows of Spotify and iTunes data into marketing dashboards, a couple of years before Spotify For Artists was a thing.”

Since then, however, he's held a number of roles, including working at Universal Music Group, as the founder of FastForward Events, and as the founder and CEO of Media Insight Consulting since 2014. But the question does then become, as a data strategist, what exactly does Carey’s role entail? Is it as simple as looking at data and crafting strategies around it, or is it more complex?

“Sometimes it's straightforward survey work, so it's just a case of ‘Can we frame a question in a way a consumer can understand it?’” he explains. “We know what our premise is, we've got a hypothesis, we know what we think the answer is, but let's ask the question in a neutral way to a representative audience.”

Often, this audience can be specific fans of an artist or the population at large, with these hypotheses tested in a way that doesn’t influence the audience so as to get a true and accurate answer.

“Other times it can be a much more strategic kind of project, but the fundamentals of it is, ‘What are the key questions? What are the sensible questions that make sense every time for a range of artists?’”

In this instance, it becomes a case of looking at the raw data and analysing it, but narrowing it down in terms of what is useful for the hypothesis at hand. “Is it interesting versus another artist who's comparable?” he asks. “Is it interesting compared to the market ratio? Your paid streams to free streams?”

While the average music fan (or often, the average industry insider) might not pay too much attention to statistical analysis and data-driven strategies, it’s the bread and butter of Carey’s career. However, while he might speak about diving deep into the nitty gritty of data and analytics, it’s important not to assume he’s someone who is solely focused on the micro level of trends and insights.

“I think unless you can do the macro, doing the micro is very hard,” he explains. “Once you get into a million rows, a billion rows of data, there are so many questions you can answer, so actually knowing what the important question is, that’s 90% of the skillset.

“Seeing the wood from the trees is the starting point, but you then also need enough understanding of what has gone on in detail. For me, most of the value I bring usually is framing the question, more so than going in and crunching numbers.

“I struggle sometimes when people just throw a lot of numbers at an algorithm and go, ‘Ah, it says this.’” he continues. “Well, it does, but maybe you've negated your role of having a hypothesis or being brave enough to commit to what you thought the answer should be, of doing the work of defining the question and then presuming that the computer has some wisdom to it.”

Indeed, much of what Carey’s role entails when it comes to analysing data is asking the proper questions. He’ll likely be the first to agree that numbers can very easily tell you a story, but they can just as easily guide you toward a narrative as opposed to if you’ve managed to craft a hypothesis ahead of time.

���If you're not going in with that larger question, it's hard to actually get the data to fit that question completely,” he explains. “You can make the number say anything with good intention, by accident of course. You can manoeuvre the numbers to say whatever you want them to say, including what you wish they said.”

A basic example of this could very easily come by way of applications to events such as BIGSOUND or SXSW Sydney, which will ask applicants about notable numbers that they’ve achieved. It’s one thing to provide an artist’s current monthly listeners on Spotify, but it might be more impressive to provide what their all-time high was. Both can be accurate, but it can be a case of manoeuvring numbers in good faith to answer a question in a different way.

“We had an artist a while back who was looking for a sync for a game which skewed male and young,” Carey recalls. “Spotify at the time itself skewed male and young, so we just shared his Spotify stats without normalising at all for the audience.

“And it won't surprise you that the audience was male and young. It wasn't disproportionately male and young on the service, because the service was also male and young.

“So you could have made it an index, or asked ‘Out of a hundred users, how do they fall?’” he continues. “It would've been one question and one answer, but since it was absolute rather than relative, it served the artist well.”

With Carey visiting Australia once again as part of the VMDO’s Music Data And Insights Summit, the question does have to shift towards some of the insights and trends that a strategist such as Carey has witnessed in the music world today.

Though he’s reluctant to give too much away ahead of his upcoming appearance, he does admit that there’s some worrying trends in the music world that have become apparent for countries such as Australia. Namely, topics such as glocalisation and the Americanisation of English language content.

“If language is treated just as one big market, which is a crude estimation of how the algorithm treats it, you will see markets like Austria getting crowded out by Germany through shared language, but also Ireland being squeezed out by the UK, Australia being squeezed out by America, and long term – arguably – the UK being squeezed out by America,” he explains.

“I think there's a circular nature to that if we're not careful that the balance of investible funds might well follow what the algorithm already approves of and therefore becomes self-fulfilling.”

This is again where Carey’s comments on the idea of self-fulfilling analysis comes into it. It’s one thing to set a hypothesis and adhere to the rules, but if you were to simply analyse current data points and plot them forward, the concept of heteroskedasticity comes into play, where one’s own assumptions get baked into the model and start repeating.

However, these concepts of glocalisation and Americanisation have been seen rather prominently in Australia recently. While there has been plenty of outcry over triple j’s Hottest 100 countdown featuring the lowest amount of homegrown names in almost three decades, there’s also been news of Australia falling out of the top ten global markets for the first time in just as long.

But, is this something that is unique to Australia or is it something a lot of other markets are facing as well?

“In regard to Australia falling out of the top ten, let's not forget that's Australians consuming global content, that's not consumption of Australian music,” Carey explains. “So much of that money might not stay in Australia anyway, and I think as a nation of consumers, you could argue is it actually becoming less compelling owing to the Americanisation of consumption in Australia.

“There's a debate to be had there. I don't have the numbers, and I'm not suggesting that American content is necessarily worse, or isn't landing as well. And of course, Australia falling out of the top 10 is the function of at least 10 other markets as well. It doesn't need to be an Australian thing for others to have caught up or to be entering the top 10 for the first time.

“But it is an interesting moment for Australia's relationship with the world as someone who has been a big exporter of music and has got some amazing artists in its legacy,” he adds.

However, with Australia in a position such as this on the global stage, is there anything in particular that Carey views the local market as doing well?

“I think BIGSOUND’s a really impressive situation,” he explains. “It's all about local talent, it brings people in from the rest of the world, and it creates opportunity. I think one of the things that Australia does really well is community. So when it gets it right, it gets it really right.

“For me, BIGSOUND’s one of the most important moments in the Aussie calendar. I get out every chance I get, and I discover talent and find interesting things.

“I saw The Buoys play recently in London, and I had the best time; absolutely superb,” he adds. “I feel like Australia is one of the few places that still appreciates guitar bands.”

On the macro level though, the music world is currently facing countless challenges on numerous fronts. Ranging from issues of artificial intelligence to low royalty payments for artists, the questions are plentiful, and often, folks like Carey are tasked with finding answers to the big issues for the music world. Once again though, Carey admits that when questions like this are placed upon him, the most important aspect of the issue is the hypothesis.

“If we were to say, ‘How do you fix streaming?’ Well, who are we fixing it for?” he asks. “Does it work for some people currently? Yes. It works very well for the platforms, currently. It works exceptionally well for some shareholders, or should I say, some former shareholders of some of the platforms. So, ‘Fix it.’ For whom?

“Well, what do we need? Artists probably need an opportunity to stay in the game long enough to become successful. I didn't go to Glenn McDonald’s session at BIGSOUND, but the question I would've asked is, ‘If you redesigned the algorithm, would you encourage it to deepen relationships with an artist rather than trying to have the perfect song?’

“I think if you put the artist, the experience, and the deepening of fans’ relationship with the artist at the heart of algorithmic behavior rather than the perfect-fit content, which is the song, then I think many more artists can live much longer in the music industry as a result,” he adds. “I think you need a concentration of fans and a concentration of revenue to get to a place where those streams add up to enough to then go on or, or enable the other ways of making money.”

Indeed while streaming might work for the consumer in the moment by way of this perfect-fit content, the question then becomes whether it is actually working for them in the long run. This is the sort of journey that folks like Carey go on while trying to answer large-scale questions like this – even if it means sometimes floating ideas which may seem controversial on face value.

“I like what Beatdapp are doing with anti -treaming fraud because if they can stop fraudsters streaming, excellent, that puts more money back in the pot for everyone,” he explains. “It's probably the only win-win situation out there.

“I'd like to see consumers pay double for streaming. That would help. It doesn't help the distribution problem, but having more money in the pot is better if streaming services don't take the same proportion. If you double prices and don't double what you are taking out the pot, 'cause your margin costs haven't increased by anything, then I think you do make things better, but not for the consumer.

“The consumer's now paying double,” he continues. “And you could quickly argue that the excellent consumer experience and the obscene consumer value for money is part of the problem for artists, and artists aren't getting paid enough.”

Chris Carey will be appearing at the inaugural Music Data And Insights Summit on April 28 – 29 to share many more of his insights and analytical discussions. Full information – including a daily rundown and ticket details – for the event are available now via the VMDO website.

This piece of content has been assisted by the Australian Government through Music Australia and Creative Australia, its arts funding and advisory body

In partnership with the Victorian Music Development Office