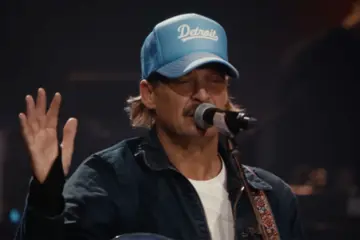

Wild Beasts

Wild Beasts"This is going to sound cheesy as fuck, but I think I've got an Australian heart," says Hayden Thorpe. The 30-year-old Wild Beasts singer has an Australian mother, who lives in Byron Bay, and his brother lives in Melbourne. He spent the first six years of his life in Perth, and when his family relocated to the North of England, he experienced his first-ever taste of culture shock; feeling out of place for the rest of his childhood. Given the glorious, melodramatic racket Wild Beasts have made over five increasingly synthy LPs — with Thorpe's sky-high falsetto a key element to their sound — surely Australians would welcome him back, here, with open arms. The only problem? "When I'm in Australia, by appearances and sound, I'm just a bloody pom," Thorpe laughs.

Wild Beasts' latest album, Boy King, finds the English quartet out to reinvent themselves. After 2014's Present Tense set the "difficult task of trying to make authentically joyous music", the banded wanted to rebel against what they felt was a "meticulously designed… music-by-maths" approach. "It felt like this very clean, considered, photoshopped version of self," Thorpe offers, "whereas this record is disgusting and sloppy, it reveals a more seedy version of self. It's like photoshop crashed and you're left with a pockmarked, not-always-beautiful vision of self; a truer reflection in many ways."

Boy King is, in part, about masculinity in all its darkness and neediness; something forever percolating in an all-male rock band. "Projections of masculinity are always to scale: the projection is only ever as big as the insecurity it's covering up," Thorpe says, sagely. Its title refers to a small being with a grand projection, charting the "swing between" the "boyish, insufficient figure and the all-commanding, all-conquering figure."

These are things that Thorpe has been dealing with; obliquely referring to "the collapse of much of [his] life" when talking about the downfalls of living out the myth of the artist. "You can yearn to be this Byron-esque character," he says, "you can have a youthful, romantic hang-up of the way an artist's life should be; can assume, naively, that beautiful art makes for a beautiful life."

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

The dissonance between Thorpe as human and as artistic projection — boy and king — leads to a record conversant in the contemporary "crisis of identity" playing out in the digital realm. "It's about the division between the authentic and the digital self. Here's me online, behind a digital filter, smiling, posing in exotic places around the world; and then there's the me that is behind that," Thorpe offers. "Previously, it was the privilege of the artist to create personae, but we each have an alter-ego now through social media. As the internet breaks down expectations of how we should socially interact these different parts of us leak out."

The album bio calls Boy King "a record for the Tinder generation"; Thorpe having dipped his toes into the online dating pool. "I've swiped," he admits. "Everyone wants to transcend themselves. For me personally, I don't wanna just hang out with artists. There's something slightly nauseating about me being in a relationship with someone who is overly familiar with what I do. There's something nice about being to just introduce myself as Hayden, without needing to add 'from the band…'"