Hugo Race

Hugo RaceGiven the fact that Hugo Race spends so much of his life on tour, we can't help but wonder if he still calls Australia home. "Yeah, just like Peter Allen and Barry Gibb and Olivia Newton-John," he laughs. "Of course." So how many languages does he speak fluently these days? "I'm only fluent in English, but I've got extended powers in Italian and limited powers in French and German," he enlightens.

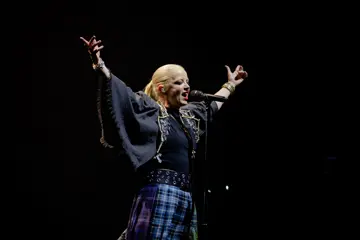

Race is releasing a new Fatalists album (24 Hours To Nowhere), about which he observes, "Nearly all my records are pretty personal and this one's no exception". When told it sounds like he's been inspired by his girl on said album, Race enquires, "Oh, is that what you think? Really? You feel a lot of positive romantic vibes on the new record?" Before admitting, "Well there's three songs on this record, I think, that I wrote with Alannah [Hill]. The title track and We Were Always Young and One Day Forever — yeah, three songs. So it was an interesting way of bringing a feminine perspective into the music and that's actually, I guess, the reason why 24 Hours To Nowhere ended up as a duet, you know, with Angie [Hart], in the end." After recalling said song "was sort of written as a conversation between the two of us", Race allows, "Actually now you mention it, [it was] really inspiring having Alannah working with me on the record in this way".

"It's part of the extreme high-level thrill that music can provide."

He's "just come off tour again", fronting Hugo Race & The True Spirit, and Race tells, "We did play every night for a month, for the second tour in Europe for our last record, so that very full-on approach is something that we still do and there's a few reasons for it. I mean, one of them is practical and economic, but the other one is creative in the sense that when you get a great group together and put them out on the road, and they're playing every night for weeks on end, they eventually reach this incredibly high level of performance and musicianship, because there's just that total familiarity with the concert; there's full immersion into doing the concert. And there's not competing distractions, because the tour is kinda like a bubble — or a continuum — in its own right. So that's one of the reasons why we still do it is to try and reach the highest level of musicianship that we can, and that still works. I don't know a whole lot of other people from our generation that are still working in that kinda way but I guess we just really love it... It's part of the extreme high-level thrill that music can provide."

Earlier this year, Race released his first book, Road Series. "I've read reviews of Road Series that've said, 'Well, it appears that he's focusing on negative aspects all the time,' and I just think to myself, 'Yes, you know, that's the point'," Race laughs. "I mean, it's not a mistake; that was the idea."

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Road Series navigates Race's restless spirit from nights spent in St Kilda's Crystal Ballroom circa 1981, via his overseas adventures - both sonic and otherwise - in destinations such as West Berlin (before, during and after the Wall came down), Italy and Brazil, and draws to a close when Race winds up in Mali, where he is regularly drawn to collaborate under the Dirtmusic guise. There are detailed accounts of relentless touring and countless kilometres driven to perform shows nightly. "It's a very powerful meat grinder to put yourself through," Race offers when these punishing itineraries are raised. "As the book indicates, it can be quite hard physically - and psychically - but I feel presently that that's part of the effort required to, sort of, attempt to achieve things at a high level creatively. That level of discomfort - and that was something that I wanted to get across in the book 'cause I often feel that, well, for a lot of the books that I've read about um, you know, memoirs if you like about musicians and such, they tend to focus on the positive aspects, so you get this rose-tinged filter over the reality. And I just wanted to do something that was very different to that and discuss a lot of the awkwardness, and contradictions and sacrifices, in a working musician's life. That was part of my motivation to write."

The writing process "was a really positive thing for me personally to do", Race says, "because it forced me to pause and actually turn around and look back for the first time in many years, and make an assessment of things and, you know, it was confronting… There were a lot of dark nights of the soul involved in the writing of it… Some events and problems from back in the time really came to the surface and they had never been resolved, those things, and I guess that's part of the process when you're creating something that's really personal."

"I just wanted to do something that was very different to that and discuss a lot of the awkwardness, and contradictions and sacrifices, in a working musician's life."

Although Race "never had time to" keep "the classic diary", he admits, "I did pick other people's brains"; specifically former Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds/The Wreckery bandmate, Ed Clayton-Jones "who recalled some very interesting things". "The things that he recalled I also used in the fabric of the narration of what was going on," Race continues. While working on The Bad Seeds chapter, Race also did some research online: "Because we were on the road for quite an extended period that year and I couldn't remember where we actually played, I found all the complete tour lists." Given this Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds tour took place "more than 30 years ago", Race marvels, "Isn't it incredible? Just absolutely staggering." Discovering this "sequence of events" meant Race was then able "to make more sense of [his] memories".

As a mad fan of The Wreckery back in the day, this scribe was particularly interested to read Race's perspective on why this promising Melbourne post-punk band imploded. Would it be fair to say the decision to break-up wasn't unanimous? "Oh, no, it wasn't," Race agrees. The book details a meeting between The Wreckery and Michael Gudinski, who expressed interest in signing the band. Petrified of 'selling out', Race walked out of the meeting. He then relocated to West Berlin. "I mean, there were several different factions within the band and each faction had specific ambitions that were perhaps less of a priority to other factions in the band so, you know, in The Wreckery there was part of the group that wanted to be commercially successful and part of the group that viewed that as being a cop-out," Race remembers, "and then there was a part of the group that saw merit in both those points of view and acted as a kind of a balance. But, you know, particularly with young bands — as we were in the '80s — there's an emotionalism about all of this that can easily spin outta control and, yeah! It often does. It's hard to keep a band together when you're in your 20s because everyone is so volatile, and everyone takes it all so personally, and I think that, you know, as you get older you take it less personally and you're more amenable to compromise."

Clayton-Jones bonded with Michael Hutchence during the filming of Dogs In Space, in which Hutchence starred and Clayton-Jones was also cast. So does Race think that being around Hutchence's level of success at this time probably increased Clayton-Jones' level of ambition? "Yeah, I think you're right," Race allows. "I think Nick [Barker] felt the same way. But there's multiple ironies in all of that and, I mean, it was those tensions that pulled the band apart. It was fascinating writing that about The Wreckery 'cause I hadn't necessarily thought through everything in all these intervening years but, when I had to address it, it forced me to look back in time and accept actually what was really going on then even if at the time, you know, we were all pretending to ourselves that we were doing things for various reasons. I mean, look, you could say that about a lot of Road Series: that actually through the act of writing it I understood a lot better what happened back [then], 'cause I never really stopped to reflect for very long about any of those things; you pass through one episode - or a band, I mean - in your life and then all of a sudden you're into the next thing, and it's overwhelming."

Race's propensity toward geographical relocation would've made it a lot easier to leave the past behind him. "It's easier to make the disconnection when you remove yourself to a completely different environment," he acknowledges, "and it's probably harder to deal with the loss of that connection when you're still in the same place where, you know, the band broke up and so on. But, I mean, obviously the impetus to keep moving has always been with me." When Race "sat down to write the book", he laughingly recalls, "I went deep into all of it". Given that Race was forced to relive some experiences that were "very close to the bone" for the sake of his book, we also wonder how he felt writing about people who are no longer with us. "I mean, look, there is elements of sadness and tragedy in all those things, but I did experience a thrill in bringing some people back to life on the page and of course when you evaluate all that objectively there is a terrible sense of loss, 'cause you realise, you know, you're whatever age you are now and the people that you used to run with that you loved - they didn't all make it to, you know, the age of 35 or something; there is a tremendous sense of regret. On the positive side, you're honouring people by positioning them inside a narrative where they live, and they breathe, and they still talk so I thought that was good."

The way technology has "transformed" - "let's say from 1986 to 2016... from the fax machine to the internet" - is also addressed in Road Series. "[It's] that whole evolution which we've witnessed around us, which I think is a story worth telling. Because there's a lot of insights within it, but also because - where we are now - a lot of the tech support that artists have is really taken for granted, and, you know, it wasn't always like that. And there's positive and negatives, I guess - like there are to everything - but I think that in some ways we were very privileged to see it from both sides: from the analogue side growing up and from the digital side in these days."

We discuss how exciting it was to be around to witness how digital technology changed the face of music, which triggers a memory for Race. "I remember the first time I heard Public Enemy, it was just... incredible!" he laughs. "I was in a bar somewhere in Germany and this music came on and I was like, 'What the FUCK is that?!' Everything was in there and I'd just never heard anyone using sampling in that way, and it was such a key record at the time. And Fear Of A Black Planet still stands up pretty well in retrospect, but there was that tremendous - it was actually a shock factor, just what they did sonically with sound, and it was very inspiring as well... Hearing that for the first time drove a lot of experimentation into sampling and electronics, which, of course, is something that I still pursue."

Race's wanderlust also extends into the sonic realm and he often struggles to divide time between his multiple musical personalities. "I'm very susceptible to novelty," he chuckles. "If there's something new coming up and I'm in the middle of doing something, I get kind of torn because I want to drop what I'm doing and go off with the new thing. And sometimes you can't do that; you have to sorta stay where you are and keep working the vision that you've already managed to come out with. But I guess that's one of my specific problems is I like to do a lot of things at the same time and so things get left behind."