Led Zeppelin

Led ZeppelinThe trick to writing effective songs is to put them in a minor key, because they’re usually associated with sadness, brooding and self-examination.

Songwriters will also tell you to use harmonisation, keep it slow to create more dynamic movement, and throw in something unpredictable to connect more with the listener.

When you have a sad intro riff to draw the listener in immediately and take them into the reel, then all the better.

Here are six examples.

LAYLA – DEREK AND THE DOMINOS

In the northern summer of 1970, US producer Tom Dowd was at Criteria Studios in Miami recording Idlewild South with the southern boogie band The Allman Brothers Band, which was co-formed in Macon, Georgia, by hotshot axeman Duane Allman.

Dowd was interrupted by a phone call. It was Eric Clapton’s manager, asking if he could come to Criteria and record with his new band, Derek And The Dominos.

When Dowd told Duane who Derek was, he replied, “You mean this guy?” and whipped off a Clapton solo note-for-note.

Allman begged Dowd to let him know when Clapton’s sessions were on, so he could come from Macon to meet him and watch him play.

As it turned out, the Allmans were returning to Miami to play a benefit concert, and Duane rang the producer to ask if Clapton would be in the studio the next day.

Dowd passed the message on. “You mean this guy?” Eric said, ripping off Allman’s solo on Wilson Pickett’s Hey Jude.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

It turned out Clapton and the band were already going to the show. They met, and that night, they went back to Criteria to drink, smoke, and jam until three the next afternoon.

Eric and Duane hit it off immediately, and Duane was invited to play on The Dominos’ album Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs.

“I was mesmerised by him,” Clapton wrote. “Duane and I became inseparable, and between the two of us, we injected the substance into the Layla sessions that had been missing up to that point.” He was asked to join the Dominos but decided to stay loyal to The Allmans.

The title Layla was, as commonly known, inspired by Layla And Majnun, a poem about unrequited love by 12th-century Persian poet Niẓāmi Ganjavi.

It was about a real-life woman in the sixth century who’d driven her lover insane and a dual suicide.

The song, originally a ballad, was directed at his best friend George Harrison’s wife, Patti.

Duane came up with the striking seven-note riff, taking from Albert King’s As The Years Go Passing By.

His original take was slower; Eric suggested speeding it up. They traded licks face to face, Clapton on Brownie, his 1956 Fender Strat, and Allman on his gold-top 1957 Gibson Les Paul.

The sadness around Layla wasn’t just to do with Patti Harrison. At the time, Clapton couldn’t cope with his guitar hero status.

He would lose Jimi Hendrix in September. When hearing of his death, Clapton cried out, “How can you go and leave me behind?”

Within a year of cutting Layla, Allman was dead. On October 29, 1971, he’d been flying along at 55 mph on his Harley-Davidson Sportster motorbike on Hillcrest Avenue in Macon, which had a 35 mph speed limit.

A flatbed truck transporting a huge crane boom made a left-hand turn in front of him, and the bike went airborne. He was 24 years old.

When Clapton played Layla to Patti, she was flattered but embarrassed. Her repeatedly turning him down led to his finding refuge in heroin.

She did leave George in 1974, and she and Eric were married in 1979. But his alcoholism and constant affairs (including with Italian actress Lory Del Santo) saw her leave in April 1987 and divorce him in 1989.

STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN – LED ZEPPELIN

It’s a testament to the sheer awesomeitude of 1971’s Stairway To Heaven that the legal sword battle over the close-but-no-cigar similarity of its opening riff to US band Spirit’s Taurus hasn’t diminished how it’s held up as a masterpiece.

New generations keep discovering it. It’s the biggest-selling single piece of sheet music in rock history. Well over one million of these have been sold, and an average of 15,000 are sold annually.

It emerged on Led Zeppelin IV, which, last year, was estimated to have sold 58 million units worldwide. The song wasn’t officially released as a single until the streaming era.

In 2016, music royalties expert Michael Einhorn told a Los Angeles court case that Jimmy Page and Robert Plant had made US$58.5 million (AUD $79 million at the time and $91.1 million today) from the song.

Page’s pensive-to-primal concept of Stairway, written in the key of A minor, was “a piece of music that would keep unfolding more layers and more moods.”

An urban legend is that Stairway To Heaven was written by Page and Plant at Bron Y-Aur, an 18th-century cottage in the mountains of Wales (no electricity, no running water), where they’d written a number of songs.

Page had actually written the entire melody at his home in Pangbourne, near Reading. Since the mid-60s, when he was still a session player, he had a bagful of cassettes on which he recorded music inspired by old blues songs updated for the space age.

But it was one night before a blazing fire at the cottage that he played the song for the first time to Plant.

Leaning against a wall with pen and paper, the singer was inspired enough to come up with 90 per cent of the words then and there, said Page.

Plant channelled the spiritual fantasy of Celtic and Tolkien writers, creating a narrative of fate and finding one’s soul. There have been hundreds of interpretations. But Plant had already sung on it, “Sometimes words have two meanings.”

The 2-minute, 15-second opening riff came when Stairway To Heaven was presented to the other two members at the converted mansion Headley Grange in Hampshire, which served as their studio because of its acoustics.

The riff is described as “an arpeggiated, finger-picked guitar chord progression with a chromatic descending bassline A-G♯-G-F♯-F” and played on a Harmony Sovereign H1260 acoustic guitar and captured in one take.

He had envisioned it with an electric piano, but keyboard player John Paul Jones suggested four flutes to give it a medieval pastoral feel.

The guitarist also wanted to finish off the 7 minute 55 seconds piece with a guitar outro, but decided Plant and drummer John Bonham had already built it up high enough.

GIMME SHELTER – THE ROLLING STONES

Gimme Shelter was the perfect introduction to The Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed (1969), an album that captured the war, violence, social upheaval and darkness as the 1960s hippie dream.

The ominous riff was recorded on an Australian-made Maton EG240 Supreme guitar.

In those days, Keith Richards’ pad in London was a crashing pad for all kinds of weird and wonderful people, most of whom he can’t remember.

"He crashed out for a couple of days and suddenly left in a hurry, leaving that guitar behind," Richards recalled in a 2002 interview with Guitar World.

"You know, 'Take care of it for me.' I certainly did."

It was pretty beat up. Richards used the Maton on two of the album’s standouts, Gimme Shelter and Midnight Rambler during sessions in February and March 1969.

"It had been all revarnished and painted out, but it sounded great," he said. "It made a great record. And on the very last note of Gimme Shelter the whole neck fell off. You can hear it on the original take."

He never used the Maton again. “That guitar had just that one little quality for that specific thing. In a way, it was quite poetic that it died at the end of the track.”

Richards’ riff started on a rainy London afternoon, apparently after an argument with his girlfriend Anita Pallenberg, already giving it a dark overtone.

But when Mick Jagger weighed in, he wanted an end-of-the-world song with lines like “rape, murder, it’s just a shot away”.

During overdubs in Los Angeles, it was decided they needed a female soul/gospel singer. A midnight call was made to Merry Clayton. She was heavily pregnant but needed the money. She arrived at the studio in curlers.

It was a hard session, and Clayton later had a miscarriage. “The song left a dark taste in my mouth,” she would admit.

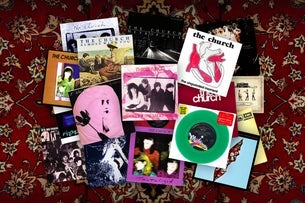

UNDER THE MILKY WAY – THE CHURCH

The Church’s Steve Kilbey and Karin Jansson, bassist of Curious (Yellow), went to visit Kilbey’s mother in her hamlet in the NSW Central Coast.

The star-filled sky was reflected in the still lagoon below inspired the haunting melody.

"I smoked a joint and started playing the piano, and (Karin) came in the room and we just made it up."

It’s usually played in E standard. The opening riff is mistakenly thought to be a 12-string tuned to Eb/half step down.

But Peter Koppes and Marty Willson-Piper actually play it with two guitars, both in standard tuning.

According to one analyst, “One is playing the standard chord progression we're all familiar with.” The other is played with a capo on the fifth fret, “playing technically different open chords with the same tonality.”

To add to the melancholy, there’s a solo composed with an EBow on a Fender Jazzmaster. Kilbey used a sampler called a Synclavier, running an "African bagpipes" sound backwards on the demo.

Kilbey admitted to the Financial Review that he used the bagpipes as a joke on the demo: "I put it on the demo as a joke, just to wake the rest of them up!"

FIRE AND RAIN – JAMES TAYLOR

In 1968, a 19-year-old James Taylor had travelled to London to audition for Paul McCartney and George Harrison to sign him up to their Apple Records, for whom he cut his first album.

It was going to be an important break for him, so when childhood friend Suzanne Schnerr committed suicide in America, his friends didn’t tell him for a few months until the record was finished.

The writing of Fire And Rain began in his rented London basement flat with him finding out about her death (“Just yesterday morning they let me know you were gone”) and grief (“I've seen lonely times when I could not find a friend/ But I always thought that I'd see you again”).

Taylor always called the song more about “shared humanity than confessional”. He returned to the US “sick and strung out, physically exhausted, undernourished and addicted.”

He finished the song in a mental hospital in Massachusetts, at Austen Riggs in in a tiny room where he was locked up and not talking to anyone. It reflected bittersweet lines about struggling with drug addiction and mental health.

The phrase about “Sweet dreams and flying machines in pieces on the ground” is not about an airline crash but the failure of his earlier band, The Flying Machine, to find success.

Taylor is an imaginative guitarist with an unorthodox approach who uses the opening riff to inject despondency to match the heavy words.

One tutor suggested, “Though Fire And Rain sounds in the key of C major, Taylor plays it in A, with a capo at the third fret. This allows the use of open strings for the roots of chords that would require fretted notes without the capo.”

Fire And Rain came out three years later on the Sweet Baby James album, recorded in Los Angeles with his kindred soul Carole King on piano and Bobby West playing double bass instead of a bass guitar to "underscore the melancholy on the song".

SWEET CHILD O’ MINE – GUNS N’ ROSES

In 1986, a year before the release of their breakthrough album Appetite For Destruction, Guns N’ Roses were working on songs in their shared house at 1139 N Fuller Avenue in West Hollywood, aka “The Hell House.”

The urban legend goes that Slash and drummer Steven Adler were about to start jamming in one of the downstairs rooms, and Slash did a warm-up exercise using the notes D, A, G, and F#.

Upstairs, singer Axl Rose heard the riff and was inspired to write the words of Sweet Child O’Mine about his then-girlfriend Erin Everly, daughter of Don Everly of The Everly Brothers.

Great story but totally untrue, Slash would tell the Eddie Trunk Podcast about the origin of the riff, “It was just me messing around and putting notes together like any riff you do.

“You’re like, ‘This is cool,’ and then you put the third note and find a melody like that. So it was a real riff; it wasn’t a warm-up exercise.”

The rest of the band fleshed out the song in the studio. The song was never a stand-out or meant as a single. But when the album came out, the radio around the world went crazy for it, and it ended up at Number One.

There were two Australian connections with the song and the parent album.

Firstly, in 2015, the Australian music media noted the similarity of Sweet Child O’Mine to Australian Crawl’s 1981 track Unpublished Critics.

When brought to his attention, Duff McKagan found the similarities between the songs "stunning," but said he had not previously heard Unpublished Critics.

Slash, when quizzed by this writer, came up with the same defence.

The second Aussie connection was that, having grown up listening to the records of AC/DC, The Angels and Rose Tattoo, Guns N’ Roses initially wanted their engineer/producer Mark Opitz to produce their album.

Opitz, however, had just signed on to make a record with the Hoodoo Gurus and had to decline.

Appetite For Destruction went on to sell 30 million copies, and Sweet Child O’Mine has been streamed 2.2 billion times.