Bright Eyes

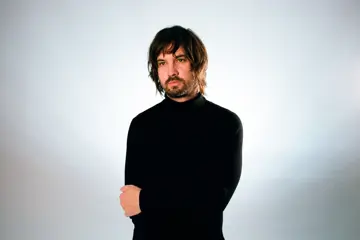

Bright EyesWhen Omaha-bred indie rock trio Bright Eyes announced in 2020 that they were reuniting after a new decade-long hiatus, that news made a lot of music lovers of a certain vintage very happy.

Bright Eyes had started nearly 30 years ago as a side-project - an adjunct to 14-year-old Conor Oberst’s ‘proper’ band Commander Venus - but quickly morphed into his main focus, Oberst surrounding himself with a revolving cast of musicians from the fertile scene which had sprung up around Omaha indie label Saddle Creek.

From those defiantly lo-fi and DIY beginnings, Bright Eyes organically built a strong and passionate following, their sometimes ramshackle blend of folk and rock given gravitas by Oberst’s intensely personal and often firebrand lyricism.

This slow but consistent rise reached the point that they captured the zeitgeist in 2014 so intensely that they simultaneously held the number one and number two places on the US Billboard singles chart, an incredible feat for an independent act.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

By the time Bright Eyes went on their extended break in 2011, they had nine studio albums under their belts - since reuniting, they’ve added a tenth, Down In The Weeds, Where The World Once Was (2020) - and the line-up had consolidated into a trio with Oberst now permanently joined by multi-instrumentalists Mike Mogis and Nate Walcott.

Oberst has collaborated with a vast array of talented friends and peers over the journey - whether that be names like Jim James (My Morning Jacket) and M. Ward in 2009 supergroup Monsters of Folk or his more recent project Better Oblivion Community Centre with Phoebe Bridgers - but he admits that teaming up again with Mogis and Walcott and dusting off the Bright Eyes moniker has been creatively like a homecoming.

“I’m slightly biased, obviously, because they’re in my band, but I consider them both to be sort of savant musical geniuses, and I mean that completely truthfully,” he smiles. “They’re neurotic as hell, and it’s hard to be in a band with them, but they do things musically that I don’t know anyone else can do, and it’s quite an honour, and I’m very lucky to have them help me present my songs to the world. Even having one of those guys in your band would be like an amazing magic trick, but there’s two of them.

“I always tell everybody - I am by far the most normal guy in Bright Eyes, straight off the bat. I’m like a regular Joe - if we meet on the street, we can go get a hot dog or do whatever you want - but those guys, they’re weirdos, but they’re very good at what they do. It’s a special thing to play with them, for sure.”

According to Oberst, the three friends and musicians share an inherent chemistry that’s only been magnified by shared experience over time (even if it’s not always perfect).

“It’s definitely grown more pronounced over the years,” he tells of their musical bond. “Even as you find these roadblocks - whether it’s creative or personal or things that involve the tours, just like in any long-term relationship, you’ll hit these impasses - and it’s like, ‘God, why are we doing this? None of us want to be here!’

“It’s not like we outright fight, but it’s like any marriage or long-term friendship: you all know each other so well and know how to push each other’s buttons, but then you also have these transcendent moments that I would never get with anybody else because we have such a shared history and have been doing this for so long.

“We don’t really have to explain ourselves to each other because I think we all know what’s in each other’s hearts and who we are as friends and bandmates, so I think that it does get stronger over the years.”

The singer explains that he long ago came to terms with the fact that hardcore Bright Eyes fans' attachment to that early body of work does not always transfer to his other musical projects.

“Getting Bright Eyes back together was a spur of the moment in regards to when we decided to do it,” he continues, “but I think we all knew that it was eventually going to come back around, and we were just all at the right points and stages in our lives when it made sense to do it again.

“And it is to some people like splitting hairs a bit - like, ‘What makes something a Conor Oberst record? Or what makes something a Bright Eyes record?’ - and the short answer is who I have playing on it. Bright Eyes is me and Michael and Nate, and Desaparecidos is me and all those dudes, and Better Oblivion is me and Phoebe and Monsters Of Folk is me and Jim and so forth.

“Then for my solo stuff, I guess, the freedom to work with whoever I want, which is nice, but there’s a certain thing that happens with Mike and Nate and I, which is pretty unique, and we really do function as a band - the three of us are equal participants in the thing.

“But as far as what the fans think about it, I feel like Bright Eyes tends to be pretty grandiose. We can’t always do it in a live setting, but this last year, on our last tour, we were out there with 14 people on stage - we can just do things that I’ll never be able to do on a Conor Oberst tour ever.

“It’s the same with recording; we’ll spend two years making a record and just drive ourselves crazy - which is great for that experience, and I think it shows in what the records sound like - and I’m not saying one is necessarily better than the other because I also like some of the more free-wheelin’, more looser recordings too.

“I dunno, to me, it’s just different and I don’t know how much of that comes across to the audience. I think also just from a practical standpoint; I remember when I first put out solo records after Bright Eyes, there were still quite a few people there, but it was quite a few less people, and I realised that there is such a thing as casual fans.

“If I really loved a band, I would probably know the name of their lead singer - I dunno, maybe not, don’t quiz me, but you know what I’m saying - whereas some people, it’s like they just don’t have any idea and wouldn’t even know if I put out a record.

“It sounds kinda disgusting to say - especially in this day and age with short attention spans and splintered media - it really is branding. And I’m the worst at branding; I’m not on social media or anything and don’t know how to do any of that stuff. And we’re so bad at presenting our band.

“It’s a running joke - or kinda a half-joke - that we’ll be at an airport with a bunch of guitars, and someone asks us, ‘What kind of music do you play?’ and a number of years ago, I took to saying, ‘Yeah, it’s called confusion rock’, have you heard of that?’ It doesn’t make any sense, and all our records sound different, so if you love one, you’ll probably hate the next one!’ That’s our own genre.”

Since reuniting, Bright Eyes have left their long-term label home of Saddle Creek - which had been originally founded by Mogis and Oberst’s brother Justin - and joined forces with Indiana indie Dead Oceans.

The first fruit of this union was the incredibly ambitious reissue series, which not only found nine Bright Eyes albums reissued on vinyl, but each also accompanied by an entire new EP revisiting the material through a modern lens.

“Like I said, we kinda always sort of overdo shit or bite off more than we can chew in some ways,” Oberst chuckles. “It basically happened because we moved our whole catalogue from Saddle Creek - which is the label we started as kids, which ran its course - and we moved over to Dead Oceans and the Secretly Group, and they’ve been amazing.

“There were nine titles that they wanted to reissue on vinyl because they were long out of print, so as a way to sort of promote the reissues - and also as kind of a challenge - we made a six-song EP for each of the nine records.

“Each one had five re-workings or re-imaginings of songs from that record, and then we would do one cover song of a track that was important or meant something to us at that time in our lives. It was a lot of recording, but we own our own studio, so it was something we were able to pull off… just.

“I remember we got about three EPs into it, and we were, like, ‘Are you kidding me? Why did we agree to this, this is crazy!’ But we got through it.”

Oberst concedes that digging through the entire Bright Eyes canon to pull off this unique achievement was ultimately an eye-opening experience.

“We had to go through and pick the songs we wanted to do, and that was - I wouldn’t say one of the hardest parts - but a very key thing, picking the material,” he reflects. “As you might imagine, the older the songs were, the easier it was to make them sound new and fresh because a song from 1995 that I made on a shitty 4-track, just recording it with real microphones makes it sound totally new, go figure. But as we got further along the project, towards the newer records, we had to think more about how we could make it sound different.

“A lot of the early recordings - the first record for sure [1998’s A Collection of Songs Written and Recorded 1995–1997] and also [2006 compilation Noise Floor: Rarities 1996 - 2005] which is a collection of B-sides from different seven-inches and compilations and stuff like that - a lot of those were some of the earliest-slash-most lo-fi recordings, and sometimes it’s the recording of a song rather than the song which makes me cringe.

“Whether it’s the sound of my voice, bad recording or production decisions we made at the time or whatever, I think at the heart of it the songs are still good, so in that sense, there was some redemption in, like, ‘Okay, we get another shot at this song, that I actually think is pretty good, and we get to do it with our mindset of us 20 years later and utilising everything we’ve learned about music since then’. That was a pretty interesting and fun sort of exercise.

“Again, I don’t know how we agreed to it, but I’m happy that we did it.”

Oberst admits that from a lyrical perspective, listening back to the emotionally forthright and honest rhetoric of his younger self was a fascinating, but at times forlorn, experience.

“Yeah, man, life’s been a wild thing,” he sighs. "I feel like I’m banged up and bruised and everything else, but I still have a lot of capacity for joy, and I have an interest in art, and I have a lot of things that I’ve seen kind of drained out of a lot of people that I love and respect who couldn’t hold onto some of those things because life got too fucked up. So, I feel grateful that I still have a little bit of wide-eyed innocence left. I don’t got a lot of it, but I’m trying to hold onto it.

“But I think that it’s interesting to me looking out when we play shows and stuff, you can see an audience of people, and there’s a couple over here who are 60 years old who probably heard of us from NPR - National Public Radio in the States - or whatever, and then you’ve got people in their 40s who are my age that grew up with us, and then you have literal teenagers, and they’re all there together. They’re all there together to see the music, and I take that as a really high compliment because it means that it’s not a fad and is transcending time.

“When I listen to or think about an album like [2000 third album] Fever And Mirrors, yeah, there’s a lot of embarrassing things on there - things I wrote and the way I sang and the over-the-top adolescence of it - but then every year somebody goes to high school and somebody’s older sister hands them a copy of it, and this has been happening for 20 years.

“So I think about it the way that I think about the first Violent Femmes record or something - yeah, it is adolescent, and there’s something that is quote-unquote cringey, although I don’t really believe in that stuff, although there’s probably something to it - but it’s also, like, if it happens every year that a couple of weird kids in the class discover it, then you must have done something right if that keeps happening year after year. I’m proud of that, I guess.”

Surely, as an ardent music fan, it must please Oberst no end that his music has become part of the fabric of that rich tapestry that is rock’n’roll?

“Oh, for sure,” he grins. “I’ve been through so many twists and turns with discovering music, and I guess sometimes the people who made it when they made it probably didn’t imagine me in the ‘90s in high school digging on their stuff.

“Like, I don’t think that Townes Van Zandt and John Prine were thinking about me when they were making those recordings in the ‘70s, even though they’re some of my favourite recordings ever made. I don’t think The Clash was too concerned that some kid in 2001 was going to try and start a punk band to sound like them.

“It’s just weird how stuff carries on, and so to be a part of that same process in some small way for younger people is pretty special.”

Oberst started writing songs at a precociously young age - his debut solo cassette dropped when he was 13 - and he’s continued writing songs his whole adult life, so it’s unsurprising that his relationship with the creative form has slightly softened over time.

“I definitely think the output has decreased over the years,” he admits. “When I was a teenager or in my early 20s, I was writing constantly, and it was the only thing I thought about, or cared about really, at all. Probably to my detriment, in a lot of ways, because I think I’ve probably ruined some relationships and made some bad decisions… I don’t know, all of the stuff that you do when you’re a kid.

“But I was so obsessed with it; it was like all I wanted to do, but then you get older. You know, I was married for eight years and then I got divorced, and I’ve never had a kid amazingly - at least that I’ll admit to,” he laughs. “But for the most part, just by growing older, I feel like I’ve seen stuff like death and mortality, which I now realise that I’ve sung about for my entire life.

“But when you’re young, there’s like a romanticism about it, but now I’m 43, and I talk to my friends who are my age or older - I have lots of friends who are older than me as well - and inevitably every conversation winds up with, like, ‘Oh, so and so’s got cancer’ and ‘This person is on chemo’ and so on and so forth.

“The gravity of life just keeps getting more and more palpable, and there is a part of me that thinks that songwriting is kinda frivolous. I had jobs when I was younger - I was the janitor, and I was a teacher’s assistant, and I worked in a record store - but by the time I was 20 years old, I was just ‘in a rock band’ for my life.

"So, it’s kind of the only job I’ve ever really had, so in that sense, I don’t really know what life is to a lot of people, but I guess it’s in this bizarro, make-believe world that I’ve been able to make a living and been able to support myself and lots of my family and friends. I feel like I’ve had to provide for people in my life, so I do know what it means to have that pressure where you’ve got to keep doing things because people are counting on you.

“People you love are counting on you - so in that sense, it’s real - but in another sense, I sometimes think, ‘Is this trite?’ Is it time to put the childish toys away?’ kinda thing. ‘What am I doing out here? I’m still singing about my fucking feelings with an acoustic guitar; this is so stupid’.

“But then you’ve got to step back and say - like we were talking about before - ‘Hey actually, this can be something important in people’s lives, this can be something of value to people’, people who you’ll never meet who find something in your music that enriches their life. I guess I try to stay focussed on that, trusting that that is still happening.

“And the money part, that’s never been something that’s ever motivated me that much; I feel it’s something that takes care of itself. I don’t really need a Lamborghini or anything like that. In fact, there’s not that much I need - I need fancy wine, and I like to eat at nice restaurants, and I want to be able to help my friends out when they’re broke - but I guess when your desires aren’t over the top, it’s sustainable.

“I always joke that I’ve never worked a day in my life, which is not true, but you know what I’m saying, it’s fine. My buddy’s a part-time musician, and if I’m ever complaining about something on tour or about something that happened, he always goes [adopts deadpan voice], ‘Hey, beats pushing a broom’. Ain’t that the truth.”

Bright Eyes are performing at The Eighty Six and Harvest Rock Festivals in Melbourne and Adelaide, as well as a handful of headline dates. You can find all the dates below.

BRIGHT EYES

2024 AUSTRALIAN TOUR

OCTOBER

24 – ENMORE THEATRE, SYDNEY, NSW

**26 - NORTHCOTE THEATRE, MELBOURNE, VIC with WARPAINT

29 – HARVEST ROCK FESTIVAL, ADELAIDE

31 – ASTOR THEATRE, PERTH, WA

NOVEMBER

2 – PRINCESS THEATRE, BRISBANE, QLD

4 – ODEON THEATRE, HOBART, TAS

**As part of The Eighty Six festival