Mark Opitz arrives at the Sebel Townhouse in Sydney for a meeting with Australian Crawl. The band is plotting how to follow their chart-topping third album, Sons Of Beaches, and launch their assault on the US market. They are keen to work with the legendary producer who has just finished Cold Chisel’s Circus Animals, Divinyls’ Monkey Grip soundtrack, Richard Clapton’s The Great Escape and INXS’s Shabooh Shoobah.

Australian Crawl’s singers James Reyne and Guy McDonough meet Opitz in the Sebel lobby. They exchange pleasantries before catching up with the rest of the band.

“Oh, before we go upstairs, there’s one more thing you need to know,” Reyne informs the producer. “We’re going to sack Bill.”

Bill is the band’s drummer – and Guy’s brother.

“He doesn’t know it yet,” Reyne adds. “So anything that Bill says during the meeting, well, just completely disregard it.”

During the chat, Bill wonders why Opitz seems to be ignoring his input, focusing instead on Reyne, Brad Robinson and guitarist Simon Binks. The drummer is not sure what’s going on, but “something was not quite right, and it left me feeling uncomfortable”.

After the band finishes their summer tour, Bill is summoned to a meeting at Binks’ apartment, where he is greeted by the guitarist and the band’s manager, Glenn Wheatley, who delivers the news he didn’t see coming: he is out of the band.

“Does Guy know about this?” Bill asks.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“Yes,” Wheatley replies. “He voted for you to stay, but the rest of the band voted for you to go. It’s been a tough decision, but James wants a fresh start with a new drummer for the [Opitz] sessions.”

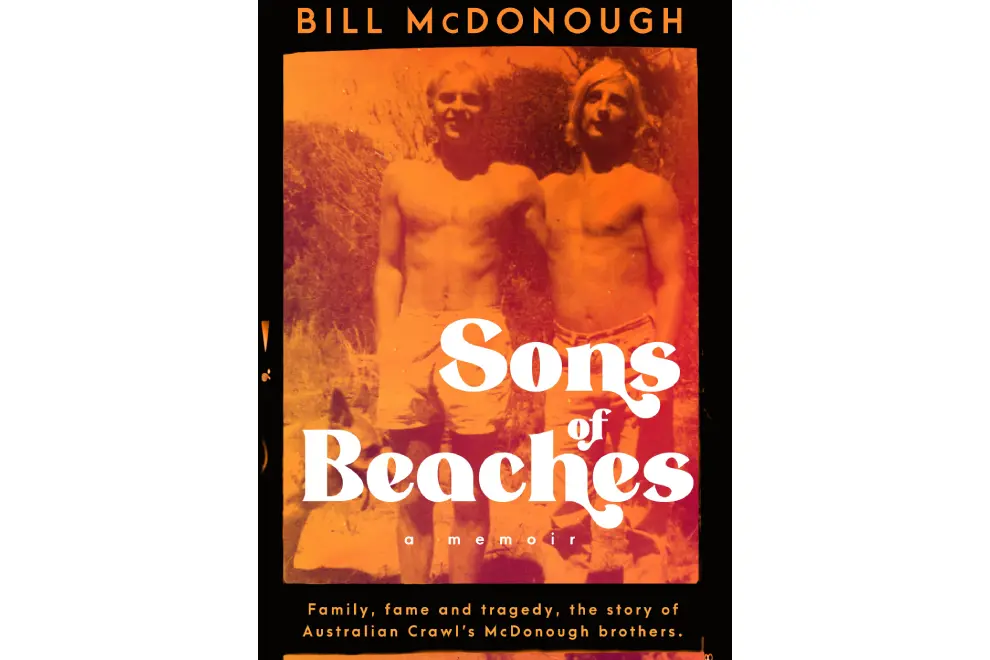

Bill’s ousting after playing on three multi-platinum albums – The Boys Light Up, Sirocco and Sons Of Beaches – is just one of the many remarkable tales in his memoir, Sons Of Beaches, which is published today, Bill’s 71st birthday.

It’s a heavy story, almost Biblical or Shakespearean. Bill had been protective of his little brother – his brother’s keeper – since their dad died of bowel cancer when Bill was 13 and Guy was 10. “Trying to protect a rebellious and risk-taking Guy McDonough would turn out to be an enduring responsibility,” Bill writes. “While I moved towards responsibility, Guy seemed to move in the opposite direction.”

After inheriting a set of bongo drums from his dad, Bill becomes a drummer. “Truth be known, I would have preferred to have been a guitarist.” Towards the end of high school, Bill’s band, Sam Blank, appears on Happening 70, and he meets Bon Scott, Vince Lovegrove and Ronnie Charles. His new-found fame at school is a revelation. “Mr Goody Two-Shoes had left the building.”

Bill meets James Reyne and Brad Robinson when they are all on the Peninsula Grammar swim team. Reyne and Robinson are four years below Bill and one year below Guy.

After high school, Bill and Guy embark on a riotous overseas adventure, living like Errol Flynn, which would later inspire one of Australian Crawl’s biggest hits. When they end up shipwrecked on Christmas Island, a police superintendent assesses the situation and offers some wise words: “Guy McDonough, you are a character. Now, you boys stay out of trouble, you hear?”

The overseas jaunt also inspires one of Australian Crawl’s first great songs, Downhearted, which Guy and Bill wrote with Sean Higgins, a member of Guy’s band The Flatheads. Guy’s first appearance with Australian Crawl is miming the sax solo on Countdown.

Bill decided to write the book after his friends were entertained by stories of his escapades with Guy. “Also, I wanted to show the readers that Guy and I had a great influence on Australian Crawl [indeed, the brothers had a hand in writing seven of the nine singles released from the first three albums]. We lived that Errol Flynn lifestyle, and we brought that to the band.

“That’s not to dismiss James Reyne, who’s one of the most wonderful lyricists I know,” Bill adds. “Songs like Man Crazy, Beautiful People and Chinese Eyes are great Aussie lyrics.”

Sons Of Beaches doesn’t pull any punches, but it’s told with a sense of humour. “Rock-and-roll rule number one,” Bill writes, “if you want women, don’t be the drummer.” Later, he’s surprised when he’s stopped by security at LA airport. “What a joke. Guy was looking like Ronnie Wood, James was the rock god personified, Paul, with his sultry looks, could have been a Bill Wyman double, and they pick me, the one who looked like the band’s accountant.”

Then there’s the band’s first Countdown appearance when the set was initially adorned with palm trees and an abundance of beach balls. When the band’s record company rep, Michael Matthews, queried the theme, it’s revealed that the crew thought the song was called “Beautiful Beachball”.

Sons Of Beaches contains some classic rock ’n’ roll encounters: lunch with Neil Young in Hawaii, beers with Glenn Frey in LA, a spa with Willie Nelson in New Zealand and being raided by the cops in Tasmania.

The book also has a generosity of spirit. When Guy feels betrayed when Reyne reneges on the plan to split the third album’s songwriting royalties, he is furious and wants to quit the band. But Bill writes that “James had every right to exert control over his songs”.

Bill’s book does, however, expose the ruthlessness of rock ’n’ roll. When the band’s first manager, Sandra Robertson, is discarded in favour of Glenn Wheatley, Bill writes, “This sort of cutthroat approach to ensure success happened time and time again during our career. It would upset me every time as I hate abandoning people who have been so loyal.”

Ironically, James Reyne sacked his own brother, David, to get Bill into the band. Then Bill was instrumental in getting Guy into the band for their second album, Sirocco. Then Guy was part of the band that sacked Bill.

Guy was in an unenviable position: Australian Crawl was on the verge of breaking overseas, having signed a major deal with Geffen Records. But the band thought Bill was holding them back musically. What should Guy do? Go with his brother or his band?

When I asked James Reyne about the sacking, he admitted: “The whole Bill situation was driven by me. It was nothing personal; it was just a musical thing. Bill will probably think I’m the worst human being until the day he dies, but I stand by the fact that it was really good for the band; the band needed it.

“We weren’t going to go anywhere [with Bill in the band], and this was our big chance. Musically, we had gotten to the point where we were actually all right; we could really play, but Bill was holding us back.

“Guy was in a horrible position. It was something that the majority of the band wanted to happen. He was obviously emotionally connected, but he went with what the majority wanted. It was difficult for him.”

Bill writes in the book: “It really hurt, but I had to go through the motions and resign so Guy could have his chance to crack the big time.”

After Bill departed, Australian Crawl made the Semantics EP, featuring Reckless, with Opitz. It was the band’s first number-one single. They also re-recorded some old songs, which were added to the EP for the international release of the Semantics album, which James Reyne believes is the band’s artistic peak.

“We had an idea for the arrangement of Unpublished Critics, which we could never do with Bill,” Reyne says. “This gave us a chance to do it. It was half-tempo until the end, and then it doubles in tempo and becomes really climactic. And Lakeside was always supposed to be a swing song, but we were forced to do it as a 4/4 song. Now we could finally do it the way it was intended.

But Bill believes his sacking was the turning point for Australian Crawl, “the beginning of the downward spiral.

“And that’s got nothing to do with musicianship, whether I was the best drummer for the band or not,” he says.

“You’ve got to understand that bands are political organisations – they’re like the Labor Party or the Liberal Party. If you choose to get rid of the wrong person, you can pay a heavy price in terms of the overall picture.

“I think if I’d remained in the band, Guy wouldn’t have spiralled back into drugs.”

Tragically, Guy McDonough died in June 1984 as the band was planning its first US tour. He was just 28.

Bass player Paul Williams told Bill that the band seemed to lose its soul when Guy died. Australian Crawl made one more album, 1985’s Between A Rock And A Hard Place and then broke up. “Literally, within 18 months of Guy dying, the band was fucked, gone, finished, bankrupt. And I don’t reckon that would have happened if I’d stayed in the band.”

Addressing James Reyne’s criticism of his drumming, Bill says, “Okay, I’m not the greatest drummer in the world, but like I say in the book, there was no virtuosi in Australian Crawl.

“You’ve got to make a judgement call on what’s best for the band overall. If I’d done the Semantics record and the [UK] tour with Duran Duran, do you reckon that would have spelt the end of the band? Would my drumming have made the difference between success and failure? I don’t think so.”

Sadly, the Australian Crawl members now communicate via their managers.

“Unfortunately, we’re very estranged,” Bill reveals. He still talks to Paul Williams – “he and I are close” – but hasn’t heard from Simon Binks since 2014 when The Greatest Hits reached #4 on the ARIA charts.

Brad Robinson also died way too young, in 1996, aged 38. Writing about Brad’s funeral, Bill states: “Now I could let go. It was time to move on. Guy was dead. Brad was dead. It was the end, for me, at that moment. Australian Crawl was dead.”

But the band is an ongoing business, with Universal Music releasing a new vinyl version of their 1984 best-of Crawl File and James announcing a solo Crawl File tour. “The way we do business is through our managers. I’ve got to speak to [my manager] Nathan Brenner, and then he’ll speak to James’ manager, and then James makes his decision, and it comes back to us. It’s ludicrous, but that’s just the way it is.”

Bill and James actually live near each other on the Mornington Peninsula. Bill’s wife, Meredith, occasionally corners the singer in the frozen goods section at the supermarket, but Bill has never bumped into him.

“James Reyne is a very complex character,” Bill says. “He will not associate with any of the band members at all.

“I’d speak to him tomorrow. If I could pick up the phone, I’d say, ‘G’day, what are you up to?’ But he won’t speak to me. He doesn’t do that just to me; he won’t deal with any of the surviving members of the band – Simon, Paul and me. But that’s his decision. I’m not criticising it; I just find it weird.”

Bill stresses that his book is not about settling any old scores. “I think you can gather it’s coming from the heart. But I wanted to set the record straight about what really happened to Guy and what really happened in Australian Crawl.

“I haven’t held anything back; this is warts and all. I can assure you, what I’ve written is the truth. This is what actually happened. Our mum died 10 years ago, and I’m not sure I could have written the book when she was still alive – it might have hurt her by telling exactly what happened to Guy.”

The week after his brother died, Bill told the press, “He was one of the very few people who have done everything they set out to do. How many people can you say that about?”

But Bill reveals that they also dreamed of starting a McDonough Brothers Band post-Crawl. “My hope was that if Crawl could break through and have some international success, Guy and I could have done the Neil Finn thing and done our own Crowded House.

“I’m a drummer and a songwriter, but I’m nowhere near the music talent my brother was. He was exceptional; that’s the tragedy. If it’d been the McDonough Brothers Band, I’m absolutely certain that Guy and Sean Higgins would have kept pumping out the hits as they were such good writers.”

Bill hinted at what might have been on My Place, the 1985 album that he compiled as a tribute to Guy.

In the book, Bill admits that he still dreams of Australian Crawl. “Some are sad, and some are full of fun and hijinks. In these happy dreams, Guy and Brad are alive, and we are all rocking and rolling mates again. That’s how I prefer to remember Australian Crawl.”

In the end, Sons Of Beaches is not your typical tale of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll. Much more than a music book, it’s a moving tale of two brothers. As Bill notes, “You take the Australian Crawl narrative out of the book; there’s so much more to what Guy and I did as siblings.

“We had quite an amazing life together.”

Sons Of Beaches is out now via Ultimo Press. You can order your copy here.