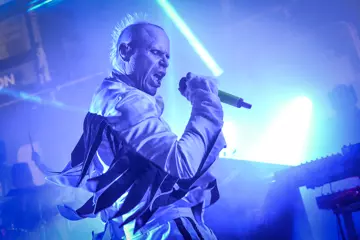

The Smashing Pumpkins

The Smashing Pumpkins“The world is a vampire,” Billy Corgan sings on one of The Smashing Pumpkins’ most menacing songs, Bullet With Butterfly Wings. Reading that line, you can hear that hypnotic opening guitar riff and pounding drums, right? You can even picture the gothic music video.

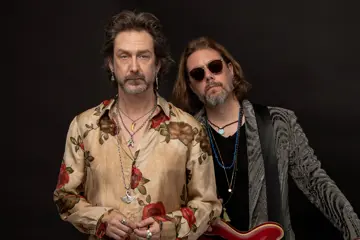

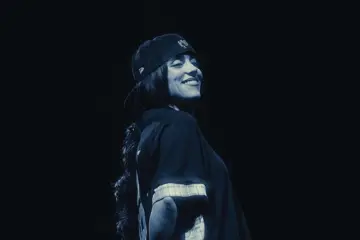

Bullet With Butterfly Wings is so magnetic and memorable that the opening line is the name of the band’s music festival, which is coming to Australia for the first time next month, with American rockers Jane’s Addiction, Aussie heroes Amyl & The Sniffers, RedHook and Battlesnake coming along for the ride.

That track stems from The Smashing Pumpkins' third album, 1995’s Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, a record that’s described as “one of the most important and artistically ambitious albums of the '90s” on Apple Music, or as Billy Corgan called it, “The Wall for Generation X”.

The record showcases the band at their most grandiose (Tonight, Tonight), their most wistful (1979) and ominous (Zero), with plenty of surprises in between. The Smashing Pumpkins weren’t just a rock band on Mellon Collie; they explored shoegaze, heavy metal, and grunge under a sheen of melancholy. Of course, it’s ambitious, and yes, it sounds like a lot that shouldn’t work, but it does.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

In 2000, The Smashing Pumpkins released another concept album, Machina/The Machines Of God. After the release of Adore, which was maligned at the time and hit Corgan particularly hard – more on that later – he took on a new persona with Machina, becoming a rockstar named Zero.

“‘Zero’, whose relationship with Corgan is obvious, hears the voice of God and renames himself Glass,” a fantastic 3 am Magazine article on the symbolism of Smashing Pumpkins records reads. “He then also renames his band ‘The Machines Of God’. Within this narrative, fans of the band are referred to as the ‘Ghost Children'."

These two albums are undoubtedly essential in the band’s history – as every album is – but they become even more so as the band’s new release, ATUM: A Rock Opera In Three Parts (pronounced Autumn), is a sequel to both of those records.

Zoom-ing in from his home, Corgan is decked out in a NWA hoodie (National Wrestling Alliance, which he owns and promotes) and ponders how he discovered the idea to reprise the overarching themes from two of The Smashing Pumpkins' most beloved records. “You know, that's a good question. Because [the album has been released], it feels easy, and there's lots to talk about.

“But when it's not there, I think, ‘Oh, God, I have nothing to say.’ And this last week, I was definitely thinking, ‘I have nothing to say,’ which is kind of a childish thing,” he admits with a laugh. But that’s not true – Billy Corgan has plenty to say about a range of topics, from his music to how constantly striving for perfection isn’t what it’s cracked up to be.

On the album rollout for ATUM, he notes, “I think over time, you develop a little bit more of a thicker skin about the thing, not because of the criticism, you just learn that first impressions are not necessarily where it's going to land over time.”

And if you look at recent coverage of ATUM – two-thirds of the record are out now, and the other third will be released on 21 April – it’s been complimented on its dynamic production but criticised for some of the synth work - what if we gave the record more time before providing critiques; would opinions differ?

“When Adore came out, [the reception] was so negative; it was so weird. It was the opposite experience of Mellon Collie, where everybody loved it, and it was great. That experience sort of scars you for life, you know, because now people really like Adore, and they consider it one of the most important albums we've done,” Corgan explains.

“You can draw a straight line from our humble club beginnings playing goth music in 1988 to, you know, headlining arenas in 1995 and being on MTV every five seconds. It's such a crazy, upwards trajectory, and you can feel that energy – the combustibility within and without is in the record [Mellon Collie]; you can hear a certain tension, which is of its time,” Corgan says. The tension only grew from there and threatened to break up the band between Adore and Machina.

On Machina, the band recruited artist Vasily Kafanov to design the album art. Kafanov has created the art for each album by the Philadelphia post-hardcore band mewithoutYou, from 2000’s A-B [Life] to 2018’s untitled. Corgan and Kafanov met in the ‘90s, and this is the artist’s story as the vocalist knows it.

“Vasily is Russian. I don't know if it's still this way, but Russia has a conscripted army, and he had to go into the army for two years. He was assigned to a remote military base on an island, and it was just him and another guy in a radio tower,” Corgan reveals. “[Kafanov] said he would find himself with eight hours of nothing to do other than wander around the islands. That's when he became an artist.

“He could just sit on the beach and draw for eight hours. Because he was on an island, there was nothing to draw. So everything was in his imagination. And I found him walking down the street in Manhattan one day; I literally said at that moment, ‘I would love you to do art for my band,’” Corgan continues.

Corgan shared the concepts of Machina, and Kafanov went forward with his artwork. “I still have some of the paintings; I know [drummer] Jimmy Chamberlain has some. I gave him free rein to do whatever he wanted, and he could translate the narrative into something that held up on its own. I like other people's interpretations of what I do. So [the album artwork] became part of our world, but it really was just his take.”

And Kafanov’s artwork is always beautiful - the first impression of mewithoutYou’s Ten Stories is of animals and a burning train trapped in the snow and features all the album’s characters – whimsical and fantastical, but always with a gothic twist. Perfect for The Smashing Pumpkins.

With Machina, the singer says he anticipated social media to come. “And what I mean by that is how the audience would have an undue influence on the art. We had to navigate it in a way; there was no manual because there was no internet manual in 1999,” he says. “In 1999, it was insane that you could put up a ten-second piece of music and literally get people's reaction in real-time; the only way you could do that before was to play a gig.

“And that required loading in and warming up and eating some food before the show,” Corgan laughs; the times changed quickly. “Now you're dealing with a digital avatar behind Joe 12345. And who the fuck is Joe 12345, and why is he saying all these horrible things about me? I’ll tell you a quick story, and it was one of the biggest mistakes I ever made.

“When [Machina] was just about done, I did something which, in modern culture, wouldn’t seem very unusual. But at the time, I invited the, like, let's call it the 30 biggest Smashing Pumpkins social influencers, circa 1999 from the message boards, to come in and hear an early version of the record,” Corgan starts. Innocently, and perhaps naively, he thought the fans would go home and write, ‘Oh, wow, isn’t it cool what Billy is doing?’ Things didn’t quite work out that way.

As Billy puts it, “I explained the concept, and they went back and said, ‘It’s a piece of shit, don’t listen to it.’ Before the record even came out, the word on the street was that the record was a piece of shit.” It came from innocence; nobody could have predicted the impact of social media culture in 1999. “I invited these people in thinking that by romancing them a bit, giving a behind-the-scenes kind of experience of the band in the studio, and then giving them the first time that anybody in the world heard the record, that it would give us like a different kind of three-dimensional advantage. And it was the exact opposite. They went to the marketplace and said, ‘Thumbs down, run.’”

Billy Corgan romanticised the idea of the opportunity to create a different relationship between artists and the audience for the first time in human history on a global scale. “Why does the band have to be constrained to videos, interviews, and records? Why can't you have a cool dynamic?” Corgan recalls asking himself in the ‘90s. “I had a very naive idea that that was going to be this cool opportunity. But it was totally innocent. It wasn't based on commercial interest but on the idea of deeper relationships, artists to the audience.”

Looking at it now, Corgan realises how misguided that idea was. “As we know, in 2023, you have to curate those experiences. I like to think [social media curation for artists] requires a certain level of sociopathic logic, which I don't possess, which is why I'm not that great at it,” he laughs. “The sociopathic tendency would be to create what people want (or don’t want) and give them more and more of it. As an artist, I just wanted to naturally share… In essence, why is my enthusiasm not enough?”

He adds, “And God forbid, in the early days of that, when I suggested that maybe there was a business model, like, ‘Hey, you create a subscription model, you pay a certain amount of money, and we'll give you all this behind the scenes.’ I mean, people were destroying me. ‘How dare you ask for money? It should be for free!’” Doesn't it sound remarkably similar to the arguments we hear online now?

Corgan believes that constant social media curation and the inherent pressure to look and act a certain way drive the media and even music. He compares the albums with the too-shiny, too-sleek production we hear today to magazine covers, where not a single blemish is allowed.

“I knew somebody who used to do professional airbrushing for magazine covers. They were airbrushing a famous person, and I asked, ‘Do you mind if I see the untouched photo?’ And they hit a button, and it was like, ‘this is one of the most beautiful people in the world. How beautiful do we need? How perfect do we need?’ And this person was explaining that with the magazines, they don't want a single blemish,” Corgan shares, feeling disturbed on a spiritual level, as the pressures for perfection imply that what’s created isn’t good enough.

The recording of ATUM came with Corgan continuously editing, stuck in an endless cycle of feeling like the album was never finished. “You have to accept that not everything can be perfect,” he admits. “That was something we certainly learned on Mellon Collie with [producer] Flood, where he was just like, ‘You’ve got to finish this shit.' Not everything can be perfectly painted.

“I think the beautiful part about that is you end up with magical moments because you're not fussing over something. And then there are other times where you’ve got to accept the blemishes as part of the architecture of the thing.” Maybe the return of original members James Iha and Jimmy Chamberlain helps with those feelings?

Billy Corgan wanted to make ATUM: A Rock Opera In Three Parts for a while, despite the unenthusiastic feeling stemming from the remainder of The Smashing Pumpkins’ members. “When we were all locked in during the pandemic, I was like, ‘I'm just going to do it; I'm not going to tell anybody; I'm doing it.’ So I just started it, and by the time I involved them, it was too late,” the singer chuckles – his bandmates know how he is; he’d finish the album with or without them. But the whole record is arriving in just a few weeks – warts (perfect imperfections) and all, and Billy Corgan didn’t need to go at it alone.

The Smashing Pumpkins are putting on The World Is A Vampire festival in Australia this April. Find tickets here. Pre-order/pre-save 'ATUM' here.