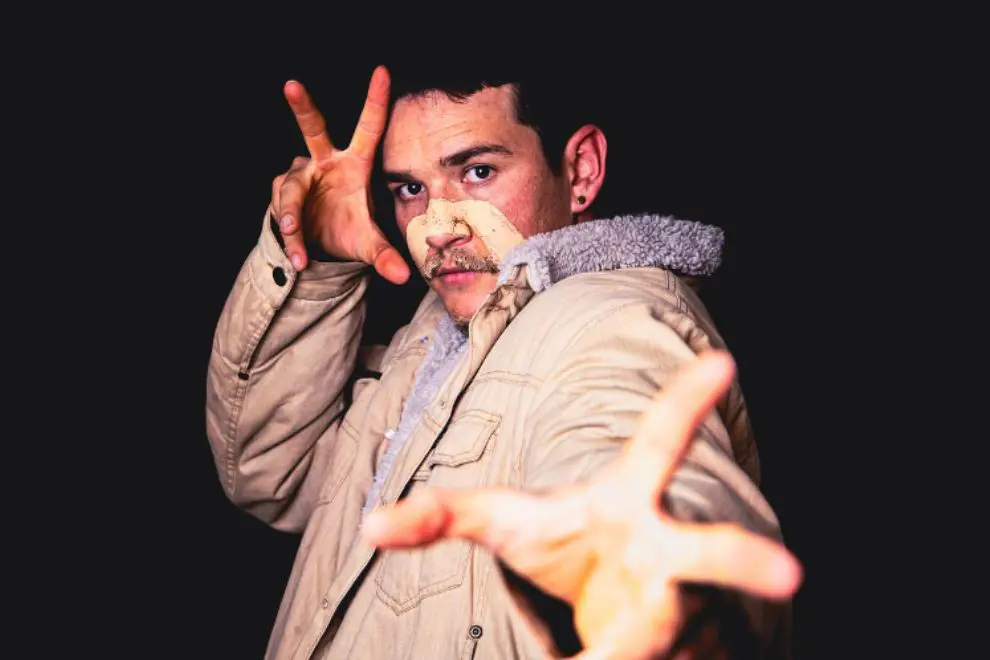

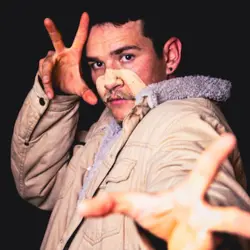

The Boy Of Many Colors

The Boy Of Many ColorsThe First Nations polymath Coedie McCarthy lives in Byron Bay on Bundjalung Country. The weather has been unusually windy and he's slid into his car seeking a reliable Zoom connection to discuss the new album The Boy Of Many Colors – an alarm reminding him of this interview. "It's a very busy time,"

Coedie says. "I just played a gig the weekend gone with Resin Dogs and then I've got a gig this weekend plus a bunch of workshops and all sorts of other creative projects happening." Coedie despairs the daily grind of Western life and digital angst in his lyrics. But today he's in his element.

The proud Yidinji Bar Burrum and Mamu man can spin a yarn. However, even his full name, Coedie Ochre Warrah McCarthy, tells a story – translated as The Boy Of Many Colors That Came In The Falling Rain. And, on his eponymous album, Coedie provides insight into how titles and language shape identity.

"I received that [name] at birth and then didn't know how much it meant to me," he explains. "It's kind of unfolded, in a way – the message and the lessons and the Dreaming of that name that I've been given."

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

There is symbolism too. Coedie's totems are the cassowary and possum – and he shares a tale from his Yidinji ancestors in Far North Queensland about Gindaja the cassowary. The "big rainbow bird" once flew, and had an aerial view, until it was disoriented in a storm, landing in muddy waters. Struggling free, the cassowary forfeited its feathers but developed powerful legs to traverse the forest floor and a casque, playing a crucial role in the tropical ecosystem. "He has this double vision of up above and down below with the people, so that's why he's celebrated as a bit of a king in the rainforest."

Coedie shows a tattoo of the cassowary's famously sharp claw on his hand. Like the flightless bird, he's acquired a unique perspective – often recognising "synchronicities" – and an ability to adapt.

A rapper, producer, didgeridoo player, dancer, visual designer and film editor, Coedie grew up in Koonorigan. He learnt about his culture from Elders before embracing hip-hop as a teen – the DIY ethos inspiring a multi-disciplinary practice.

Advancing his formidable wordplay and versatile production skills, Coedie determined to combine tribal music and hip-hop, conceiving the empowering group Indigenoise – popular on triple j's Unearthed platform.

Indigenoise joined the roster of Hydrofunk Records – launched by Resin Dogs' Dave Atkins and DJ Katch in 1995 and is now Australia's longest-running independent hip-hop label. "That hub, community, family, up there is such a network to be a part of – it's been the biggest blessing for my music journey," Coedie says.

Indeed, the creative appreciates that his relationship with Hydrofunk feels "authentic" and "more than just a transaction." "We never had any official business side – it was [a] handshake," he reveals.

"Everything's been run correctly, but we didn't have to sign in or bloody compromise or all of the things that I'm discovering other artists sometimes have to go through. So I've been really free just to be an artist."

In 2018 Indigenoise debuted with the album Old Ways New Age – Coedie referring to it as "the learning phase."

"That was us finding our sound as a group back then and finding our morals and all of the other things that are involved in music as well – like we were really looking at our identity yarn back then.

"We didn't do much collaborating, because we were trying to really nail our identity before reaching out so we knew who we were and where we stood in this industry, in this landscape, as musicians – which I think is important, because there's so much watered-down and bloody Hollywood sparkly [music]; all these different versions of music that you can get lost in it and following trends and things like this, which is sick for the party vibes, but I like to send my message and really hone in on that storytelling side."

The collective established themselves on the live circuit – and even played at the countercultural Burning Man festival in Nevada's Black Rock Desert. In recent years US pundits have decried how Burning Man has been ruined by Silicon Valley tech bros but Coedie was gratified to experience an inclusive community.

"It was still just mindblowing sensory overload. Really beautiful community – like everyone sharing, caring. There's no money. All of those [good] things that you hear are true. So, yeah, regardless of there being the rich playground dynamic, there's still a bunch of real people there doing epic shit." Closer to home, Indigenoise appeared at Splendour In The Grass' Global Village in 2019 – Coedie returning last year.

Coedie commenced his solo project as the world locked down during the pandemic. Unable to perform, he instead finessed his production nous. As such, he accumulated a surplus of material. It was a special time, Coedie also becoming a father – his partner Indigenoise member Roslyn Barnett (he now has "two little bubbas"). Listening back to the songs, he hears them differently.

The album's lead single, Good Mourning, is Coedie's rawest foray yet – the MC addressing the impact of colonial dispossession and the looming existential threat of climate change. He released Good Mourning in September 2022, just as media coverage of the Black Lives Matter movement dropped off.

Coedie welcomed the response. "I didn't think that your big hitters, our big radio and people like that in this country, would jump on it – but they did and got the support behind it."

Alas, the crushing failure of the 2023 Australian Indigenous Voice referendum has set back reconciliation – ensuring that Coedie's truth-telling in Good Mourning as well as Burn The Colony (featuring buzz Meanjin neo-soul singer DancingWater) are more relevant than ever.

"It's been a political landscape for our people since everything happened in history," he says. "So I think, either way, the music and the songs that I've put in here, some of them are quite politically charged and speaking on the story. I think that's always going to be relevant because of just the nature of how our societies have collided." He rues, "[But] it's a positive out of the chaos to see that synchronicity and kind of alignment, I guess."

Still, on The Boy Of Many Colors Coedie expresses many emotions. He's super attached to his current single All Be Fine, describing it as "a bop".

"I think that one is further from the traditional old cultural concepts, art, that I was creating on the album – and that one's more towards just celebrating being an artist, being human, being a musician.

"Blackfullas are political when they're born; they're born into a position of responsibility. It can be pretty heavy and hard to hold at times. So I think we really need to give space for especially young people just to be artists and to celebrate them for being artists…

"So that's me going, 'Ahhh, I don't have to be political and neither does any other Blackfulla in this space – you should see our artistry as well.' It's just time to celebrate sometimes."

Latterly, Coedie has collaborated with Emily Wurramara (the Black Lives Matter protest song When A Tree Falls), New York diva (and PNAU cohort) Kira Divine and First Nations EDM star Moss. And The Boy Of Many Colors is communal. Notably, on the Latin-flavoured Bravado, Coedie vibes with Barnett – her voice soaring. "I was so happy to hear her magic back on that track and back where it's meant to be."

Coedie approached old friend Ash Grunwald to add some "grungy, bluesy rock stuff" to Shaken, which broaches '90s West Coast rap – the pair working over Twitch.

"He was neighbours for ages and we didn't get to connect when we were living next to each other – like we did, we knew each other and surfed together, but didn't get to jump in the studio. I saw him in the surf years later and just went, 'Look – let's do it' and essentially hit him up for whatever he wanted to input on it." Coedie hopes in future they might perform Shaken together live.

Coedie is particularly proud of The Bay, featuring Coopsie – "a young up-and-coming deadly talented kid." He mentored Coopsie at SAE Institute Byron Bay – "a cool full circle" moment for him. The Bay also finds Coedie challenging himself by dipping into UK grime. "It's such a style to nail – I don't think just anyone can do it. But it just started flowing and I was like, 'Sick, this is so fun.'"

A recurring theme in Coedie's art is the duality of tradition and modernity. Curiously, as a practitioner, he distinguishes between tradition and culture: tradition being passed down but culture dynamic and continuous.

"Culture is not what you do, it's how you do it, for me – and that's how I've always been taught. So it doesn't matter whether it's a modern music style; it doesn't matter whether it's theatre, storytelling, [or] all of these other things that we have today… It's how you accomplish those things and how you frame it and the energy you hold while doing it. It has a lot to do with holistic thinking and being and the nature that you hold.

"A culture can never change – and it's a living, breathing culture that's never died. You can't kill it, because it's how you do it, it's not what you do. So that's how I see my practice today. I have many different forms and my music's just one form of my culture."