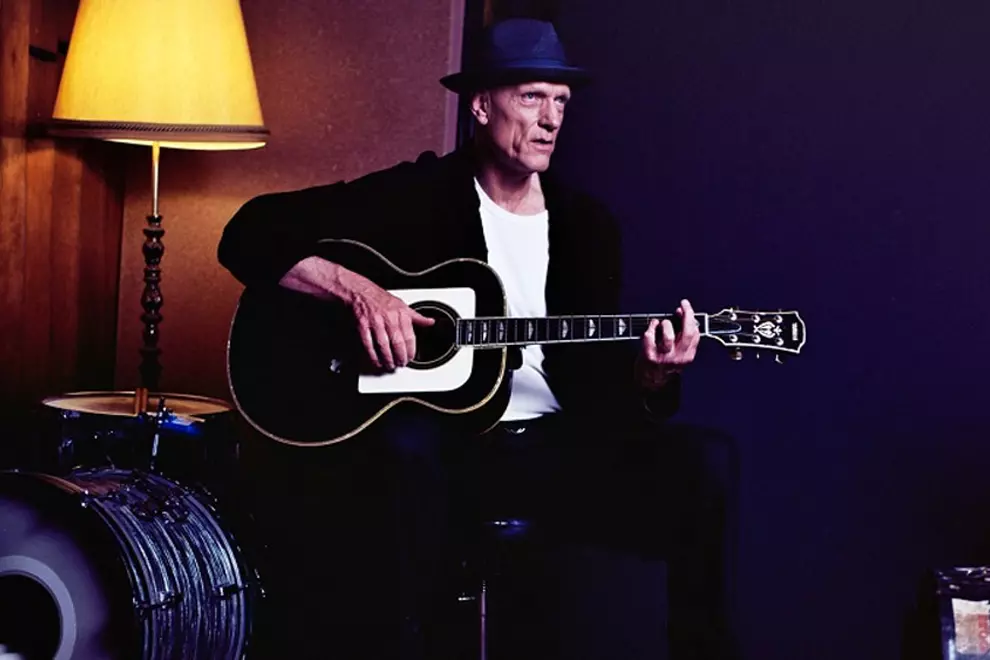

Peter Garrett

Peter GarrettAs frontman for world-respected rock activists Midnight Oil, Peter Garrett spent a quarter of a century trying to make people think and dance in roughly equal measure, before deciding to put his money where his mouth is and attempt to facilitate actual change in the political sphere.

Eventually, after a tumultuous decade spent as a Member of Parliament for the ALP, including two separate high-profile ministerial portfolios — firstly as Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts in the Rudd regime, eventually taking over as Minister for School education, Early Childhood and Youth in the second Gillard ministry — Garrett left the cutthroat world of party politics and inevitably returned to his first love: music.

Once he started flexing his creative muscles again to pen 2015 memoir Big Blue Sky, the songs began flowing naturally and, despite never having released music under his own name before, Garrett immediately knew that this batch of music would be best suited comprising his debut solo album, A Version Of Now, rather then being left on the back-burner to await next year’s highly-anticipated Midnight Oil reunion.

"It’s the kind of thing that you don’t want to talk about too much because otherwise you jinx it." — On recording new Midnight Oil material

“It’s all happened so quickly, it’s been amazing,” the singer marvels. “I think I just really pulled a stopper out when I got the book done and, because I’d put a bit of a fence up around myself to try and get it finished, it meant that when the music came we just got on with it pretty quickly, so I really haven’t had a chance to think about it that much.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“It seemed that they were very personal reflections that were happening to float around and I cradled them a little but tenderly to begin with and thought, ‘Well, let’s hold that as something which was pretty just me just peeling back a layer of skin and sharing it.’ Obviously [Midnight Oil guitarist] Martin [Rotsey] came and played on it, and that was very cool to have him as a part of it because obviously we’ve played together for a very long time. And then just pulling other people together and getting in and doing it, it never really felt like it should have been a holdover. Who knows what will happen with the Oils recording-wise — we’re obviously going to play quite a bit next year, and I know that everyone would like to be creative as we go — but it’s the kind of thing that you don’t want to talk about too much because otherwise you jinx it.”

Did it feel good tapping back into that creative mindset and working in the artistic realms in anger again?

“Oh, most definitely,” Garrett enthuses. “I was really kind of standing on air and lifted up into the air a little bit when it happened. I mean, you’ve got to work at finishing them and getting them to work, but they all did come pretty quickly, except for the last couple. To rewind a little bit, I didn’t have that many [songs] and I just thought I’d go with what I’ve got. I know that when I’ve got something — and you would talk to people about this whether they’ve been making records for years or just starting — but you do have to grab it and get it down; you should never let it go.

“So I kinda knew I had to do that, but at the same time I wasn’t sure there was going to be any more to come, and then I thought, ‘Well no, why not?’ I could sense something there and I felt an old battered acoustic guitar in the corner of my study was just going, ‘C’mon mate, pick me up! Get on with it!’ It was almost supernatural, like a mini plaintive Jack Black had inhabited my acoustic guitar and was saying, ‘We gotta rock!’” Garrett bursts into laughter at his own extraordinary imagery.

It seems from this recounting of the creative return that the words and music were arriving together, and Garrett explains that while it occasionally happened that way there’s no hard and fast rule about how the songs were manifesting.

“It’s a little bit together and a little bit mixed,” he tells. “I think I had a couple of scratch lyrics — and I had a couple of songs as lyrics which I’d put at the front and back end of my memoir — and Kangaroo Tail I’d mucked around with a little bit but it was almost like a folk song, so I’d let it go. And I’d Do It Again, all I knew was that I had a bunch of words but I didn’t know what the tune would be. So I really started with those and another one that I wrote, Only One — it was almost like closing my eyes and seeing where my fingers ended up.

"Sometimes you’ll really slave over something and you don’t know until you’ve got it where it needs to be, and then you come back a month or two later and go, ‘Hang on, what happened there?’"

“And, as you would know better than most, guitar playing’s not my strong suit — I’m the original hack with a capital ‘H’ — but I kinda just found my way to things that I felt made me feel like this quiver of intense excitement in the fact that there was a note, a song, a word, and then I just kept on wrestling with it and going with them. I mean, I did a bit of music throughout the [1981 Midnight Oil album Place Without A] Postcard era but I mean there’s [guitarist] Jim Moginie in the band and Rob [Hirst, drums] so there’s never any shortage of music, so basically I had other roles there — lyrics obviously and other bits and pieces — but I’ll always chime in if I think something musically needs to go in a certain direction. In this case, I was starting from very much a blank page, which is kinda cool and nice, so I thought the simpler, the better, and let’s just try and do justice to the idea and not overthink it.”

The music on A Version Of Now is a rich, rock-based tapestry that, while not as potent as Midnight Oil’s often incendiary aural onslaughts, serves these songs perfectly. Yet Garrett explains that this result was just a by-product of the process rather than a concerted effort to wander a new sonic path.

“Nah, not really, I just went with what I had,” he tells. “I mean, Great White Shark is an old song that [Midnight Oil] had a go at but never really nailed, and in some ways it probably feels like the most Oils-y thing on the record, but for me it was just a case of really trying to do justice to the words and the melodies and the tunes, and end up with something when we got into the studio that people could play and, because we put the band together pretty quickly and really didn’t have a lot of rehearsal time quite often, I just called the changes — particularly with Heather [Shannon, The Jezabels]’s keyboards, I’d just call the changes as we went.

"Sometimes you’ll really slave over something and you don’t know until you’ve got it where it needs to be, and then you come back a month or two later and go, ‘Hang on, what happened there?’"

“I mean it’s kind of half old-school and half new-school: half old-school in the sense that it was a band playing in a studio but getting the takes pretty quickly, and then having a listen afterwards; we didn’t spend a whole lot of time with overdubs — Martin did a few things here and there — and then Burke [Reid, producer] mixed it all on ProTools because you can get the job done pretty well nowadays with that. It wasn’t until we were mixing it that we sorta thought, ‘Hang on a minute, that sounds interesting’, ‘or ‘That’s got a ska-y, Clash-y feel’ or whatever the descriptor is, but I never really had anything in my head before I went in.”

The results speak for themselves, the nine songs each standing proudly on their own but also hanging together perfectly as a single entity.

“I’m proud of it,” Garrett smiles of the album. “You don’t know until you’re done, and sometimes you’ll really slave over something and you don’t know until you’ve got it where it needs to be, and then you come back a month or two later and go, ‘Hang on, what happened there?’, and people are going, ‘Yeah it’s not bad. It’s pretty good…’ and then there’s that pause, that ‘dot dot dot’. But I think the other thing about it is that in a sense liberating this creative side of my head in order to put something down that had a musical and words component; it’s kind of my first love so I was really very relaxed about where we ended up, because I thought, ‘Wherever we end up is a true reflection of where I’ve ended up’.”

As well as Rotsey and Shannon, the band that Garrett assembled for the project — which he’s since dubbed The Alter Egos — includes drummer Pete Luscombe (Paul Kelly, RocKwiz) and Mark Wilson (Jet), the musicians seeming to gel together well right from the outset.

“Yeah, well, I mean if you get players of that calibre then it makes your life just a pleasure to be in the studio with them,” Garrett luaghs. “Martin and I had been out in the bush so we’d mucked around a little with some of it, and he was able to do sort of almost like half an MD role at times with things. Pete Luscombe you’d know well, obviously he’s like the quintessential drummer, particularly for being able to go from one field to another. And he’s got his own distinctive style — it’s a very economical style — but he’s also pretty versatile. Then, with Mark, I kinda knew about the Jet thing but I actually listened to some other stuff he’d been doing more recently with some friends — I can’t think of the name of it off the top of my head — which I really loved, so he was kind of a natural fit. Then it was the same with the keys: I’d heard The Jezabels — because I haven’t had a lot of chance to listen to much new music over the last ten years — but I loved what they were doing, and I thought that there were some really interesting keyboard sounds happening. And people thankfully said yes!

"I had to remind myself that it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that you love music for music’s sake, and not because of where it can take you … in career terms."

“Also I think having Burke in there as well was important — he’s a really intuitive producer, he’s all about the feel and capturing the moment and kinda pushing it a little bit. I remember, in an age before a lot of your readers were even thought of as twinkling little stars, where you’d sit in front of a console and you’d sorta be nudging the red and going to the producer and engineer, ‘Come on, let’s kick it along!’ — in this case it never got out of the red! I’ve never seen anyone punish the mixing desk quite like it! It’s fantastic! I can’t speak highly enough of him.

"We haven’t had a lot of producers who’ve come through as musicians to begin with and then taken that musicality but are also across all of the technical sides, and then who develop the smarts to kinda get the best out of people in the studio. I was really chuffed that he said yes. I didn’t really know half the things that he’d done — I took my take off The Drones’ records because I quite like that air around the vocals on The Drones records, and there’s really something quite volcanic happening there at times. Then there was Courtney Barnett and Sarah [Blasko] and some of the younger bands that he works with — these sorta crazy speed-metal bands — and he’s open to anything, which to me was really the key, because I had to remind myself that it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that you love music for music’s sake, and not because of where it can take you, and by that I mean in career terms, or what it signifies to the wider public.

"You’ve just got to love it for what it is, and in that sense you do have to record and listen without prejudice. I think if you do that you’ll just end up with something where the palette’s got a little bit more breadth to it.”

After an adulthood immersed in music, did stepping away for a decade change Garrett’s perspective of what the art-form means to him?

“I think so, but it was such a busy and intense period that I didn’t really have much reflective opportunities at the time — I was just really just thinking about trying to do the job as well as I could and bat away the crap that kept coming over the horizon,” he ponders. “I think it was probably more when I finished. I used to listen — I would probably listen to radio and some of the stuff that I’d grown up with that I like, a little bit like having a dummy as a baby — if you can go back and listen to some music that you like then you don’t feel quite as bruised — but it probably wasn’t until I got halfway or three-quarters of the way through the book, and then I found that in the afternoons [it was music time].

“I don’t know if everyone’s the same or if it’s just me, but I’m pretty good to write all morning and maybe into early afternoon, but once that early afternoon comes — that stretch from 1.30pm through to about 5pm — I found it really difficult to keep the concentration and the focus going so I started listening to things and I started fiddling around, and that’s when the guitar started calling me. It was actually a really amazing working routine because I didn’t expect it to end up with music. I’d start writing about education reform or whatever and I’d end up mucking around with F-sharp.”

Garrett has a long affiliation with the Outback which harks back to the Oils’ halcyon days, but the trip out bush with Rotsey and some other companions — which ended up colouring a lot of the album’s tone — was not ostensibly to seek musical inspiration at all.

“No, not so much,” Garrett tells. “I spend a little bit of time out there, and even when I was Minister I got out. Ever since way back in the day, when Oils did the big desert run with Warumpi Band and then Blackfella/Whitefella [the 1986 tour of remote aboriginal communities] and then we did Diesel & Dust (1987) after that, I kinda maintained some connections with some of those communities in particular. And I was actually going out in part to see if some of those things that I was trying to push through when I was in politics had actually happened, because it’s such a long way away from anywhere else that quite often you can be the person with the biggest title and the biggest desk and the biggest department and nothing happens.

“So I really wanted to get out there and just gently cruise through communities just saying hello to people and seeing whether a couple of the things that had actually gotten done. And I just took a couple of people along with me including Charlie McMahon — the didgeridoo player from Gondwanaland — and Martin and my brother.”

Had those changes he’d strived so hard for actually occurred?

“Yeah, that was a happy result that the things we’d tried to kick off — and they were only little things — but they had happened,” Garrett admits. “I mean, there’s some big challenges in remote Aboriginal communities full stop — that’s a bigger yarn for another day — but some communities, I think, were really rolling up their sleeves and getting on with it. There’s been so many changes from Canberra, and I was really conscious while in Canberra having spent to much time out there before as to how 'easy', in inverted commas, it is to come up with a policy direction, to organise some budget for it, to get a bunch of officials and bureaucrats sorted to do it, to work with the administrations and land councils and whatever it might be and say, ‘Okay, this is where we go’, and then just walk away and think you’ve done your job, where, in actual fact, it’s the opposite: you have to really see that stuff through in a very tangible way down on the ground where it counts, and you’ve got to work with people — you can’t just be issuing edicts from Canberra or Brisbane or Darwin or whenever.”

"It came together quickly pretty much; there’s a few clunky lines here and there but I didn’t revise and edit too much."

Turning to some of the specific tracks which make up A Version Of Now, the dense imagery of opening track (and first single) Tall Trees seems a forthright statement of intent with lyrics such as, “Like a Boeing safely landed, a vessel that’s been stranded, I’m back” — was it important to so matter-of-factly address his return to music?

“I don’t know if I thought it was important but once the song was done I thought, ‘That’s track one’,” he tells. “It came together quickly pretty much; there’s a few clunky lines here and there but I didn’t revise and edit too much, I just wanted it to all come out. Sometimes I’ll just sit there with a big white sheet of paper and just give myself an hour to see what emerges. I think that took about an hour and then we had it, which was good.”

The next track, I’d Do It Again, is a strident look at Garrett’s own political years, another area of his recent life that he felt compelled to address on the album.

“Yeah, absolutely, I think there’s a lot of misconception about, firstly, politics generally — there’s a lot of suspicion and mistrust and people are disappointed,” he reflects. “And sometimes rightly — I’d strongly emphasise that there’s plenty of good reasons for people to be disappointed — but in many ways a natural part of my life was to find places where I could throw my shoulder against the door, and that happened to be one of them so of course I did. And it was consistent with my values set, but a lot of those things either you’re not supposed to spend your time explaining when you’re in politics, you’ve got to get on with the job.

“And I really made a decision while I was there to not spend too much time just simply responding to attacks and a universe full of pundits and social media commentators and critics and everyone else, because you could spend your whole life doing it and you wouldn’t get any work done. So I really just wanted to get the work done as best as possible, but it was obvious to me, talking to people, that they didn’t quite understand why I’d done it or really what had happened, so here was a chance to essentially just lay down my own thing. At least it’s a song. It’s in 4/4 so it’s acceptable.”

"I think that one of the schematics which came out of it was a sense of homecoming in the very broadest way, and a reflection about a life that’s been pretty full-on at times."

Garrett came under an incredible amount of scrutiny during his political tenure; he must have thick skin to shrug off the unrelenting attacks which seemed of all conceivable natures.

“I’m lucky,” he chuckles. “I feel it but I was born with DNA which is not too bad for that. I’m a little gnarly.”

The album’s following three tracks — No Placebo, Homecoming and Kangaroo Tail — all deal with the recurring motif of “home” in different ways.

“Yeah, and I think that one of the schematics which came out of it was a sense of homecoming in the very broadest way, and a reflection about a life that’s been pretty full-on at times, where I’ve stepped out and occasionally stepped off the ledge,” he states. “Sometimes I’ve been like the Roadrunner and got a huge whack, and at the same time having this… not so much being in a bubble, but sort of breaking out, as it were, back into the things that lift us all up, really, and of course one of those things was being back amongst family and being home and then thinking about that more broadly. And mortality and the future and some of the bigger things, but just in a responsive way — I wasn’t trying to be too philosophical about it, it was just catching the thoughts as they drifted in and then getting them into the songs.”

Then Great White Shark — which, as mentioned earlier, was nearly an Oils song back in the day — proves that Garrett has lost none of his empathy for environmental issues.

“Yeah, I’d sort of reworked the original lyric a little bit because I sort of feel that it’s important that we continue to say those things,” he admits. “I mean we wrestled with Great White Shark quite a bit — it was probably the one that took us the longest period of time to get down, because if it was like something that was completely new and just really simple you’d just say, ‘Look, this is the way it goes and then you’ve got the song’, but this was something that’s been around for a while and has got a few twists and turns in it, so it takes a little bit more time to sort of pull it up. But as it ended up I love the sound of it — I don’t even know quite what Burke did but, whatever he did, it was good.”

The next two numbers, Only One and Night & Day, are personal reflections on the importance of relationships and familial commitment, the closest things to direct love songs he’s conjured in his lengthy canon; was it nice to work in these different realms for a change?

“Yeah, very much so,” he concedes. “Again, I knew that it was just a case of just letting it out onto the page, and just expressing that feeling at that time and getting people to play together in that same spirit. And then I could just walk in and sum up with the vocal that feeling of affection or whatever. We all spend a lot of time trying to find a path — if we’re musicians or artists, we’re trying to find the distillation of the creative impulse, if we’re in the business or we’re writing about it and we’ve got jobs we’re also looking for the connections and relationships and partnerships, and sometimes that means that if you’re lucky enough you might find someone who’s happy to hang with you for a long period of time, and in my case that definitely happened. It was almost inevitable that it would come out in song, although again it was slightly unexpected, but there it was and it had to go down.”

Garrett even had his daughters Emily, Grace and May in the studio lending their voices to several of the album’s tracks.

“Yeah, it was fun,” he chuckles. “I had to finish a couple of them over Christmas because we recorded them in January, and they happened to be down for Chrissie and they’re Garretts, so they sing, and they sung along. And I said, ‘Oh well, do you want to come and do it in the studio as well?’ and they were really up for it. Originally we were only going to do a couple of songs, but there was something about their voices — they’re not professional singers but sonically and in terms of the mood it seemed to work as a nice counterpoint to everything else that was going on, so that’s been a huge blast.”

The album’s final song, It Still Matters, is almost a distillation of all that had come before, tying everything together conceptually and then raising some more compelling points to contemplate in a machine-gun burst of ideas and imagery. Did that closing statement arrive late in the piece?

"I’m not trying to launch a solo career or anything like that, but by the same token I’m like anybody else — I want people to like the music I’m making."

“Yeah, that’s the last one actually, you’re spot on,” he continues. “I sort of needed another song in some ways, and I also had this idea that I wanted to do something that effectively did sum up… the journey’s a bit of a clichéd word, but the path so far. I really wanted to try to, in a sense, provide some dimensional viewing and listening to both the record itself and also my own kind of views on things. And I like hip hop — it’s not a hip hop song, but I think you can do a lot vocally with that spoken narrative that you hear in rap and hip hop, so again we really took it in and I had a little thing on my phone — because you can record all this stuff on your phone, who would have thought? — but we had a day before we went into the studio so we just started playing it, and Pete and Heather and Martin and Mark were all in there with Burke and it all just literally grew from that moment. I was just happy that we were able to do it justice, really.”

It seems the perfect conclusion to what in totality can only be seen as an excellent return from the musical wilderness.

“Great, I’m really glad it’s working,” Garrett grins. “I’m not trying to launch a solo career or anything like that, but by the same token I’m like anybody else — I want people to like the music I’m making, what’s the point otherwise?”

Now it’s time to share the new music with the public: is he looking forward to the impending live shows and getting back into the onstage spotlight?

“Oh yeah, hugely; it will be a great buzz,” Garrett gushes. “It will be intimate and I like that. Abbe May’s playing with us, which is awesome — I was so stoked she said yes; I was honoured, really — so it will be fun. We won’t have a lot of time to get it in shape, but I don’t think that’s really going to end up a problem for us because everybody’s good players. And Mark and Pete and Martin are all available and coming out, which is great because they made the record. I think it will be a good night.

“And I think these songs are going to translate well live. We spent a day [rehearsing] with Abbe recently because she’s on the road doing her own thing, so the other day we spent a day with her in Sydney and started to run them down, and as we were doing No Placebo I was thinking, ‘Hang on a minute, is this going to work live? Maybe we’ll just add a bit in here’, so I think it’s really just going to be a trip, just lifting them again to another level.

“And it’s a quick album. As you know, the Mac and ProTools recording revolution has been marvellous on some levels because people can make music in their bedrooms, but it’s also dangerous, ProTools, because it gives you this infinite number of shots at it and infinite number of mixing options and it could drive you crazy — it would drive me crazy! In some ways that was the rational me saying, ‘I want to be creative and intuitive with everything that I’m doing here and I feel incredibly lucky that I can have a crack at that’, but at the same time I know that we’re not going to go for too long, we’re just going to make it and just let it rise or fall, whatever it’s meant to be.”