For a long time, I’ve been trying to learn how to sit with discomfort. In 2016, I moved to the other side of the world. There, a friend and I would repeat that we were becoming “comfortable with being uncomfortable”. We were meeting new people, we were navigating new cities, we were starting new types of jobs. We were being constantly challenged – whether by grisly winter weather, a change in lifestyle, or solo travel.

It goes without saying that we were privileged to even be able to up and leave for two years, with no one to answer to. What we were learning was to accept the discomfort of our new home, and almost revel in it. I felt that same deep sense of discomfort for much of Mona Foma, but had to, at the same time, acknowledge how lucky I was to be there, as a part of a thriving artistic community for four days. That sense of being ill at ease wasn’t to do with how welcoming the city or festival itself was, or its quality, but with the way any performance or art installation made me feel. Yet there were moments that eclipsed that disorientation.

Orville Peck @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Orville Peck @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Those moments included seeing Canadian mystery cowboy Orville Peck command the festival mid-afternoon, the first artist on Saturday to get the crowd up and moving, eliciting a collective “Yeehaw!” at the end of his set. He was also the first person to really seem to be having fun on stage, emerging past gusts of smoke before cycling through songs from his debut, Pony. Somehow he was more emotive than anyone had been on the Saturday, even if all we could see of his face were his eyes and the grin behind the fringe of his mask. He and his band would duel with their guitars, hopping about the stage, Peck landing on his knees. While everyone in the band was dressed in their best denim and cowboy hats for the occasion, horses sewn into their vests, all eyes were on Peck – all swagger and drawling charm, requesting that people go out and support their local drag queens, which he described as today’s most subversive art form. At the end of the set for Take You Back, to the crowd’s delight, Peck and his band competed to see who could hold their whistle the longest, with the artist himself taking the crown.

CHAI @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

CHAI @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Japanese dance-punk band CHAI performed three times across the weekend – first on Friday night riffing on their Favourite Things with Laibach, Amanda Palmer and more, then on Saturday afternoon at the smaller Traverser Stage, before a mainstage slot on Sunday, dressed each time in oversized pink shirts, red, high-waisted, very short shorts, and pigtails. Their joyful rock songs stirred the crowd to dance – you could actually see people each day transition from curious spectators to full-on fans, caught up by the band’s contagious enthusiasm. A festival highlight came each time lead singer Mana would come front of stage to ask, “Do you have body complex?” She explained how she was insecure about her eyes and legs, but was learning to embrace herself as “the new kawaii”. It was a lead-in to NEO, a song which encourages people to love themselves: “You are so cute, nice face, come on, yeah!” Later, the group of four emerged in turquoise-coloured, brightly tasseled capes, to perform a choreographed dance for This Is Chai, to howls of appreciation from the crowd.

Ripple Effect Band @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Ripple Effect Band @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

There were times throughout Mona Foma where it felt like the festival would be better served by a stronger local contingent, rather than so many headliners from abroad. The all-women Ripple Effect Band, from a remote part of the Northern Territory, sang in four Australian First Nations languages, set to an upbeat soundtrack and stripped of artifice. On Sunday, singer Chloe Alison Escott expressed queer and trans poetics for The Native Cats’ energetic and captivating set, including the punchy Preservation Law, sometimes falling to the floor and kicking her legs up. Iranian-Australian musician Gelareh Pour from Melbourne’s ZÖJ explained her instrument, a kamancheh, and the Persian poetry she was singing in Farsi. In this way she helped the crowd to understand what they were doing, rather than shutting out people without prior knowledge of their work.

The Native Cats @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

The Native Cats @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

I worried that the acts that most appealed to me were the ones that didn’t make me feel uncomfortable – exactly what I was trying to learn to overcome. But some sets seemed impenetrable, whether they were the oddly liberating cult/church service vibes of Holly Herndon and her fellow singers, the very heavy metal of Zeolite travelling through the whole festival precinct, or Robbie Avenhaim’s pulsing solo drumming. I wondered whether so much sometimes discordant sound is art in and of itself, and if noise really could drive people to a transcendent state. In some cases, it did, the crowd warping with the artists, while at others people seemed disengaged, even as they were awash with sound or watching people play with the full artistic capacity of the voice. Many artists showed us how experimental music could be danced to or added a theatrical element, from Herndon to Jeremy Dutcher’s community-building the next day.

Holly Herndon @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Holly Herndon @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

As I sat against the wall inside the tribute to the work of Karlheinz Stockhausen, 50 years after he played in Launceston in the very same venue, the eerie soundscape became difficult to bear. There was nothing to consume except that dissonant, all-encompassing sound, which saw some people enter the free event only to round the corner back out again. I was failing to meet the festival on its own terms, to see it as a place where strange and wonderful work could sit beside much-loved artists, and play off one another. It was certainly more forceful and disorienting than your classic eight-band festival line-up. That difference was seen even in the festival’s commitment on sustainability, with punters furnished with real cutlery, cups and plates, which, along with food waste, was arranged into something like art of its own.

Faux Mo @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Faux Mo @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

I get claustrophobic in dense crowds, so I struggled with the beloved Saturday afterparty Faux Mo, and its tribute to Dolly Parton. We were packed into the Launceston Workers Club to witness Simone Page Jones, accompanied by local country singers, drag queens, and people dressed as sequinned koalas, rev up the crowd. Then she sent us into the alleyways to see people playing bagpipes, DJ sets, and sometimes disturbing video art from David Henry Nobody Jr, who manipulated his own face into something nightmarish. It was hard for my Sydney brain to comprehend an evening so stimulating and jam-packed, going way into the wee hours where stranger and stranger – and lewder and lewder – events occurred.

The festival felt sewn into the fabric of Launceston’s cultural life, events drawing upon the unique character of the spaces in which they’re housed. Video art installation The Centre, at the Elphin Sports Centre, matched the sight and smell of each room with the work inside, from the largest basketball court filling with the cheers of devoted Western Sydney Wanderers football fans, to the men’s changeroom hosting the sweat of competitive bodybuilders in Turkey. The first work, Wonderland by Khaled Sabsabi, sucked you into the crowd, gripped with their fervour, while Ali Kazma’s story about bodybuilding was fascinating, the camera glancing over the men’s glistening muscles, their faces tense with desperation. That combination of sport and art brought in a diverse crowd, from young families to curious teenagers.

Bodybuilding @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Bodybuilding @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

King Ubu, a collaboration between the festival and Terrapin Puppet Theatre, grappled with questions around gentrification and entrenched generational inequality (a song is literally called Boohoo Baby Boomers), set against the jaw-dropping backdrop of the First Basin of Cataract Gorge. The work took full advantage of that setting, using spotlights to engage a young audience searching for the Prince that would save the city of Launceston, and the entire state of Tasmania, from the scourge of Boomer greed embodied by King and Queen Ubu. He was illuminated on the other side of the gorge, and on the chairlift, and by the shoreline. He was the next generation, ready to preserve a vibrant community at risk, the star of a story that was fun and playful, and took advantage of the weird darkness – and body humour – of certain children’s stories, and suitably big for this grand venue.

King Ubu @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

King Ubu @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Not only did the work engage with its setting, but it engaged with the community itself. It poked fun at the very idea of an arts and music festival taking over a city, at our privileging of the power of investment, refusing to position itself as an inalienable good. It was more complex than that – and also more interesting. King Ubu took that discomfort, our word of the day, and made it into a cheeky work of theatre. And free theatre at that, which welcomed local families and visiting mainlanders alike to marvel at Terrapin’s astounding, bright and strange puppets, made by Bryony Anderson, and with perfect sound design by Dylan Sheridan. The work also engaged with the city by including the community in the work, from the City Of Launceston RSL Band, led to play surf-rock-inspired tunes by festival director Brian Ritchie, to Allstar Cheer & Dance, to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s Youth And palwa kani Language Programs. Ritchie was just as ripe for parody as any other element of the festival or the city, and was described in one song as thinking “art can save us – we’ll be dead by December”. The festival then wasn’t a kind of parasitic presence but rather a part of the vibrancy of Launceston, and with the ambitious King Ubu, garnered an audience that might not be the targeted audience for the Festival Hub. Ritchie’s The Toiletbrushes would go on to perform songs from the play as the Mystery Set to start Sunday’s proceedings in the Festival Hub.

Daedalum Luminarium @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Daedalum Luminarium @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

The UK’s Architects Of Air took up Royal Park with Daedalum Luminarium, a blow-up prism of colour and light. The fact that it looked like a brightly coloured jumping castle in a park by the Tamar River meant that it appealed to children –again bringing families into the sometimes esoteric festival. As a space of quiet meditation, people soaked in red, green or blue light, but when lying under its patterned roof, it felt at odds with the bursting weekend energy of kids. Still, it was beautiful and oddly soothing, and it repositioned a public space in service of art, drawing 10,000 people through its egg-shaped domes.

Hypnos Cave @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Hypnos Cave @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

The work that most creatively reimagined a local space was MESS and Soma Lumia’s Hypnos Cave, which took as its scaffold the Penny Royal’s Dark Ride. Instead of taking a boat ride through Tasmania’s convict history, we – and 4,000 others – bore witness to a rave that was just out of reach, and moving at the steady pace designated, had no option but to be consumed by it. Each section of the ride was marked by different pounding beats and melodies, the ride’s animatronics stripped of their skins to psychedelic effect. There were lasers and video works, bright lights, taxidermy and moving skeletons, an oddball collection akin to a real-world Willy Wonka’s Wondrous Boat Ride.

Flying Lotus crowd @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Flying Lotus crowd @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

The unsettling feeling, which was quickly taken over by a sense of wonder, was how we felt at the end of the weekend at the Festival Hub, mouths agape watching Flying Lotus’ 3D set. After being warmed up by a DJ set from Oren Ambarchi, the crowd wore green glasses, psychedelic imagery jumping out at us as FlyLo laid siege to his decks. It was beguiling and thrilling, encouraging us to let out the last of our festival energy on our feet as we questioned our relationships with spaces and shapes, and danced to his experimental rap, which featured collaborators like the late Mac Miller, Kendrick Lamar and Thundercat.

But any discomfort conjured by the 3D imagery of Flying Lotus’ set didn't compare to the sense of dread inspired by Laibach’s sets. The Slovenian industrial band played the headline slot on Saturday, drawing upon the fascist-styled imagery for which they’re well known, and playing songs like Opus Dei, military-influenced The Whistleblowers, and pop electronics-turned-thrash, Resistance Is Futile. As others bopped along, a surprising amount of children appeared on shoulders to watch Milan Fras growl into the mic and then retreat, arms behind his back, and his bandmates standing at attention behind their instruments. Their stage presence was off-putting, deliberately detached and almost disdainful, especially due to the strangely demanding computer-generated voice that offered generic festival platitudes, like “We love you,” or “Hello Europe, we are so happy to be here.” When it would repeat, “Make some fucking noise,” it wasn’t a request but an instruction. They bowed goodnight after an encore cover of Rolling Stones’ Sympathy For The Devil: “That’s all, folks. Thank you and goodnight.”

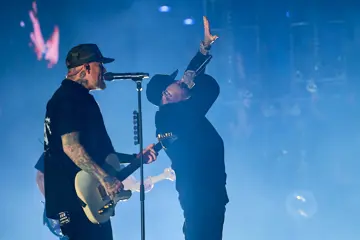

Laibach @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Laibach @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

We were encouraged to wear earplugs for their experimental set the next morning, where they played in a pitch-black lecture theatre. Vitja Balžalorsky sawed at his guitar with a violin bow. Bojan Krhlanko used a cymbal to bash his other cymbals, in a full body movement, before resting it and producing yet another cymbal. Fras only emerged midway through the set with a megaphone, to shout something like “Oi!”, over the electronic cacophony. With imagery of war and propaganda projected behind the band, it was another uncomfortable moment, which forced us to think about how the iconography of this band predates the rise of the right in the world today, and whether using the language and imagery of fascism reinforces or parodies totalitarianism.

Read More: Amanda Palmer On Her 'Hyper-personal, Accidentally Feminist, Extremely Direct' Record

Amanda Palmer closed out Mona Foma on Monday night with a four-hour show, and Palmer herself seemed to embody the mantra of sitting with discomfort. On the weekend she had set up a Confessional in town – her own The Artist Is Present moment – with people coming to her to spill their sadness, and Palmer acting as a self-described “emotional tourist” and “sadness vampire”. From there she was to write a song from what she gleaned – a logical extension to her latter-career, Patreon-led flash songwriting style. She repeatedly spoke about how uncomfortable she was to be sharing a work so raw and new with the room, but she too overcame discomfort in a display of vulnerability akin to her exposing social media presence. The result of the experiment was the centrepiece of this show, which leaned heavily on winding songs from her latest album, There Will Be No Intermission, including The Ride, Machete, Drowning In The Sound and A Mother’s Confession.

Amanda Palmer @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Amanda Palmer @ Mona Foma. Photo by Jesse Hunniford.

Much of the show was also dedicated to Palmer explaining her artistic practice to her devoted fanbase, and saw her justify an earlier career controversy around the song Oasis, which showed the way some women compartmentalise the trauma of abortion. For the song to be followed soon after by Voicemail For Jill showed just how far Palmer’s compassionate songwriting has come, even as her theatrical and compelling vocals remain intact. The set also explored her earlier work, from Runs In The Family and Ampersand to The Killing Type and Dresden Dolls classics Coin Operated Boy and Mrs O. She sang in the stalls for In My Mind before launching into early crowd favourite Map Of Tasmania, which saw the crowd shout along, “Fuck it!” A capstone to the evening came with the crowd reading off spray-painted sheets for a cover of Midnight Oil’s Beds Are Burning. All in all, the show was a display of Palmer’s tenderness, and her relationship with ’art’ and truth, and with her audience.

Ultimately Mona Foma is a festival of transgression and cheekiness, of arbitrary boundaries joyfully stamped on, and spaces re-envisioned for new uses. Visiting Launceston for the weekend forced me to again sit with my discomfort, and to examine it, so hopefully, I grow and take a newfound self-awareness into the world with me.

Disclaimer: The writer was the guest of Mona Foma.