Modest Mouse

Modest MouseEight years between albums would be a long time for most bands, but Seattle-based indie icons Modest Mouse don’t work by anyone else’s standard methods of practice – their drive and ambition is based purely on their own terms, outsiders and their expectations be damned. Their fans are important – hence the years of toil – but music industry machinations have no place in their messed-up kingdom, pandering to the man being far too straight-laced and proper an avenue to even be a consideration for this most idiosyncratic of acts.

Still, you would have thought that time was of the essence to a degree even for Modest Mouse given their recent career trajectory. Forming in Issaquah, Washington back in 1993, Modest Mouse existed in the margins of the alternative world for the best part of a decade – slowly accruing a fervent fanbase with their strange, off-kilter arrangements and frontman/chief songwriter Isaac Brock’s eccentric and oft acerbic worldview – until in 2004 their fourth album, Good News For People Who Love Bad News, suddenly catapulted them firmly into the mainstream. The record and its crossover hit single Float On were both nominated for Grammy Awards, and suddenly their music was not only ubiquitous but embraced wholeheartedly by masses of people who until that time hadn’t even known that the band existed.

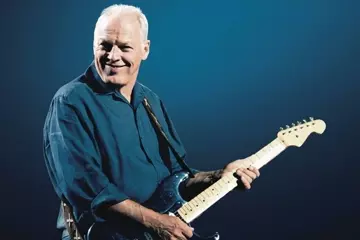

From there things just kept getting stranger for Modest Mouse. In 2006 Johnny Marr – legendary guitarist for UK iconoclasts The Smiths – joined their ranks, adding his distinctive tones to their next album, We Were Dead Before The Ship Even Sank, which incredibly hit the top of the Billboard album charts, completing the most unlikely of Cinderella transformations for this most willfully and steadfastly strange outfit. They had conquered the system which they’d shown no interest at all in conquering, and obviously in the process left themselves with a conundrum about what to do and where to go next because the next few years became a blur of rumour and speculation about their creative collaborations and intentions. Marr was gone – having amicably disappeared off the radar – and further line-up changes occurred as the band remained squirreled away in Brock’s Portland studio Ice Cream Party working on what would gradually take shape as their new opus. They emerged at intervals for tours and festivals, but for the longest time actual new Modest Mouse music remained a concept rather than a reality.

Now, eight years on, they’ve finally emerged with their sixth long-player, Strangers To Ourselves, which despite its obviously convoluted birthing process is a robust continuation of the Modest Mouse lineage, a typically uncompromising album which if anything harkens back to the pre-fame era in which they toiled happily away in near obscurity.

"But truly and non-butt-lickingly, I fucking love playing Australia.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“I’m as happy as I’ll ever be, man,” Brock posits of the new record. “I could be happier, but I’m happy, shit. If I was left to my own devices then I’d probably still be fucking with it, so it’s probably for the best that we put it out. The last nine months I spent working on it were probably a bunch of lateral fucking moves, you know? I’d be tweaking with it but it may not be any better.”

Brock owns and runs an indie label which he named Glacial Pace, so he’s clearly aware of his personal foibles regarding time issues. He has, however, mentioned in recent interviews that the recording process for Strangers To Ourselves was so intense that he thought he was dying at one point – was it as bad as he made out or was that claim dramatic license?

“Yes and no,” he chuckles. “Life’s fucking intense man, and if you spend a good deal of your life working on something then those intense moments are going to land there too. It wasn’t as intense as maybe recording those last couple of things we did with Dennis Herring were – that felt like psychological warfare at that time – so it was generally a pretty peaceful process, although it was also pretty feverish. So much fucking work went into making it.”

Herring produced both Good News For People Who Love Bad News and We Were Dead Before The Ship Even Sank but his controlling methods had rubbed Brock the wrong way, and after trialling numerous producers for the new album he ended up taking the production credit himself. Strangely, Brock admits that he didn’t know what he wanted from the album before or even during the process.

“I think if I’d tried to steer it I would have ended up steering it off a fucking cliff,” he ponders. “In general I just let things be what they’re going to be to an extent – once I can make out the hazy image of what it’s going to be then I can step in and steer it in a direction, but in the first fifty percent of getting a song to that point you just kinda let shit fall in place and try not to have too many restraints on what it’s going to be. At several different points I knew exactly what I wanted, and at several different points I then realised that I didn’t want that. There were moments of fucking clarity of purpose where it was, like, ‘This is what I’m doing’ – and this was an actual plan by the way – ‘I’m going to make the most boring record that I possibly can!’ Just something that started nowhere and went nowhere, and not for the sake of being pretty and things – it was partly because the scramble to be interesting chips away at me and is just a heap of trouble all the time, so I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll just make a record that’s so fucking normal it’s weird?’ Then I got bored five songs in and harvested the organs from some of those songs and started off on my merry way with a new lack of direction and shit – I just wandered into the wilderness again, I’d lose that direction and find it again and then shitcan that too. But at the end of the day it’s probably just a collection of a whole bunch of focused ideas and concepts, but no I didn’t know what the fuck I was hoping to make when I went in there – I never do and I never probably will.”

What about all of the other potential producers such as Outkast’s Big Boi and previous Modest Mouse collaborators Brian Deck (Built To Spill, Iron & Wine, Califone) and Tucker Martine (The Decemberists, REM, My Morning Jacket) who had been attached to the project in the press?

“Well, with the Big Boi thing that was pretty damn premature on our end – we only had five songs that we were all that happy with when we went to visit the dude, or hang out and work, and the danger of enjoying hanging out with someone is that less gets done than it should,” Brock recalls of their brief Atlanta sojourn. “So we ended up partying a lot – we worked until eight in the morning and shit still, if you can call it work – and just trying it on.

"Science cannot explain what happens when we get into that fucking zone."

“That was the only attempt at trying on a different producer that we had actually done prior to going in, and when the time rolled around that we were going to be recording the record for real me and my friend Clay Jones – who’s helped on this thing – decided that we were going to do it. I was, like, ‘I don’t know man, I do not believe that I should be producing my own record’. I really enjoy the outside input – as a writer I’m sure you appreciate sometimes having an editor, even if they take out your favourite bits. I dunno, Kurt Vonnegut always thanks his editor. But I appreciate that dynamic for the most part – having someone that hasn’t been just so in the reeds that they can’t see clearly that this is actually super, super lame this thing you’re doing; “Granted he loves playing that part, but why are you playing it? It’s fucking stupid, stop!” I enjoy that. But anyways, a year-and-a-half rolls around and I have been talked into it – me and Clay are producing this fucking thing – and then we got ten days into and I fired myself. I was just, like, ‘Dude, I am fired! What I need to do is say is that the producers are fucking up, and I can’t do that if I’m one of them, so I’m going to go stand over here with these guys and say that you’re fucking up’.

“Then we tried that for a while and then all of a sudden my friend Clay’s left holding this fucking pretty big bag, and he worked for a few months and it seemed like it was going to take forever – he’s very, very good but just so fucking meticulous that it was painful. We’d be standing around and at that point we didn’t have heat in the building yet and there was water everywhere so we just huddled around this desk that had been left there by the previous owner, and just put out every fucking space heater we possibly could. The whole building is windows – some sort of cellophane-thin glass from 1947 or something when apparently being warm didn’t matter or something. But he edited shit for fourteen hours, and we were, like, ‘I’m pretty sure in fourteen hours we could play it as well as you’re going to edit it?’

“So anyway he goes away and then we got Brian Deck in to work on it, and Brian Deck is a badass in his own right – he’s got his own ways of doing shit – but unfortunately most of the producers that we worked on with this record do not exist in the space and time that Modest Mouse does: science cannot explain what happens when we get into that fucking zone. So these guys had like three months which seems to them like plenty of time to really kick ass and make a record, and to us that sounds like enough time to smoke some cigarettes and fucking get super-stoned and force these fucking dudes to let us make shit with all the mics in water barrels or what-the-fuck-ever. We had all sorts of aborted creative plans which ate up incredible amounts of time.

“So anyway Brian comes in and he has shit that he has to do on a certain date, and that comes and goes and we’re nowhere near being done with the record so we get someone else in – Tucker Martine comes in to help, and he’s super fucking helpful. The only thing is though that I guess I tricked him, because I said, ‘Can you come in and help me for a few days and sort these files? I need some outside input’. So he came in to help me for a few days, and a few months later he had shit to do. And then we ended up working up with Andrew Weiss and that motherfucker’s badass! He produced two of the songs on this record and three that will end up on the next record – he’s produced some Ween shit and a couple of records for The Boredoms, some pretty fucking out there stuff, and he was Henry Rollins bass player for 12 years and played bass for Yoko One and Ween. I love that dude, he never wore shoes; I just saw him in New York a week or so ago and he had shoes on, and I was, like, ‘What’s going on dude?’ and he said, ‘I do not walk in New York without shoes’, and I was, like, ‘Really? So we’re cleaner in Portland?’ So anyway he came in towards the end of the thing, when there were only five songs left that none of the other producers had wanted to touch these fucking things. And I’m, like, ‘I really like these weird things – currently I like them more than the other things because they’re so fucking weird!’

“So it ended up that we had a bunch of heads in the building helping produce and stuff, but it was largely because they were gone for most of it that I ended up having to do it – so I rehired myself without telling Andrew. The stuff that Andrew worked, Andrew produced that stuff. Man, one of our guys was hiding from him at one point – he’d keep track of where he was in the building and try to shift from room to room. If we didn’t say ’Cry mercy’ or some shit we’d just be working for 48 hours on stuff. At one point he asked me to remove all of the soft syllables and S’s from an entire version of a song – or something like that, I don’t remember exactly what it was – but I was, like, ‘Fuck you, don’t you tell me what to fucking do!’, and I went in there and wrote this long-ass line using nothing but all of the things that he’d asked me not to use, and I went in to show him and I expected him to get that I was being passive aggressive and shit because he’s smart and I figured he would have got it, but he was, like, ‘That’s perfect!’ I was just, like, ‘Fuck! Fuck!’”

What about the mixing process itself – some of the complex arrangements have so much going on in the margins that it must have been time-consuming to say the least?

“It was Sisyphean,” Brock thunders, referring to Greek mythological figure Sisyphus who was doomed to an eternity of pushing a large rock up a hill, only to watch it roll back down again. “It was so fucking hard to mix that thing. I’m still not truly happy with the mixes – that’s where I think I can still win the thing. I’m still going to try to be honest, just for my own fucking peace of mind I’m still going to try to mix some of these songs again, just so I know.

“But we’d mixed the entire record fucking nose to tail with this guy Joe Zook in LA, and then I decided that I didn’t like any of that so we mixed the whole fucking record for a few months with John McEntire and I didn’t like any of that, so for the eleventh hour shit me and this guy that lived at the studio and who’s a badass engineer him and I are now mixing, and just trying to figure out how to get me happy.

“So we started putting a Joe Zook mix on top of a John McEntire mix – I don’t know if you know mixing much, but that is something that is not to be done – but a song on the fucking record is done that way, which caused an incredible lot of phase aligning and stuff like that but it fucking worked man! But mixing was hard – the more sounds you have the smaller those sounds end up having to sound to make room for other things. Let’s say we’d have an epic kick-drum sound, something really fucking booming, but on that same song old Mr Brock-weed would want two beats: not one beat, but two beats super fucking low and distorted – that would be Shit In Your Cut, that song – and then there’d be all this other shit. There’s just not enough room for everyone to actually do what they need to – some of those sounds are amazing, but you can’t make 20 tracks of keyboards… It’s just so difficult, I’m still getting my head around it.”

One of Strangers To Ourselves’ indubitable strengths is the typically dense and verbose lyrics – large tracts of seemingly stream-of-consciousness jumbles which somehow combine into a complete and enlightening whole. Does this side of songwriting come easily to Brock?

“Ummm, yeah,” he admits. “The initial part of it – just spitting out shit and finding out that I agree with it and being surprised by myself – that part’s fucking easy and fun, and my favourite part of the job. Sorry, did I just call it a job? If it keeps the lights on in the house then it’s a job, there it is. So anyways, that first part is fucking easy, but the hard part is… When the first part happens I get to tap into my subconscious and dig through whatever is lying around, it’s like an impromptu fucking yard sale of information and shit, or more like a marathon burglary, I dunno – but then I need to tie this all together to something that makes it a song, and that shit’s fucking hard. Parts of it are easy though is the answer to your question.”

Does he write down ideas in a book to remember as he goes about his daily life or does he prefer the Nick Cave method of treating it like a vocation and making time to sit down to write a song?

"I don’t know if it’s possible ever not to be frustrated with humanity, because we’re a fucking mess."

“I write to remember in a book, but I never sit down with a cup of tea and say, ‘It’s time to pen the masterpiece!’ or any shit like that,” Brock continues. “I’m not really one for that, that’s not really how I can creatively do it – maybe something will pop into my head and I’ll have to write it down to make sure I remember it or so I can at least embarrass myself a week later when I come across it and go, ‘You’re a fucking idiot man, why would you write that? I’m sure there’s a high school somewhere that someone will be interested in this to write it on their notebook!’ There’s a lot of that.

“I’m a pretty poorly-focussed dude on some levels, and one of those levels is maintaining organised notes of shit, which I learned how to do on this record because I had to do both producing and mixing so I needed very detailed notes of exactly what and where I wanted things – that was pretty fun. But I don’t sit down and write lyrics out and then try to wedge them into a song – usually the music is already there, but the phrasing to the lyrics of a song sometimes happens at the time, like bolts at the same time big bang style.”

Is there a lyrical theme throughout Strangers To Ourselves, or some overarching premise tying the tracks together?

“Yeah, shit tons of stuff,” Brock tells. “They all came from the same pool of me wandering around – it’s one dude’s brain – and the things that were specifically on my mind tended to be an aggravation with, myself included, humanity. I don’t know if it’s possible ever not to be frustrated with humanity, because we’re a fucking mess. That and there were a lot of thoughts about nature and so on and so forth – they all tie together in one way or another. Not all of them – some songs are just fucking stories. Like the song everyone hates, Pistols – which I love and I put it on there because I thought, ‘Maybe everyone will hate it!’ – that’s just about a three buck scumbag in Miami, and has nothing to do with anything other than, ‘Isn’t that fun?’

“I mean it’s not a concept album, but there’s a bigger picture – it all fucking ties together, and that’s usually the job, at least with our band, of the record title. The title connects all of those fucking pieces, no matter how disjointed they might seem from one another, and that’s one of the hardest things to fucking figure out how to do for a record – that last little thing, looking at all of the shit and thinking, ‘What is this called that makes it all make sense, to me?’ Whether it works beyond that shit kinda remains to be seen.”

For years Modest Mouse’s founding bassist Eric Judy acted as Brock’s creative foil during the songwriting process, someone he trusted implicitly to bounce ideas off and be told when he was heading down dead end paths. Judy, however, left the band suddenly during the album sessions – was he missed during the last period of creating Strangers…?

“Shit yeah!” Brock stresses. “That relationship was a huge part of our songwriting thing, probably more than he ever gives himself credit for. I never actually think that I ever took him for granted on that level, but it was a tremendous loss. It kinda forced me to do more work than I used to – and I hate that – but vibe-wise he was pretty missed, man. Hopefully he’ll be back at some point – we’re not entirely sure why he left, he’s been pretty quiet about it. Jeremiah [Green – percussion], him and I are still in touch – we’ll talk and do texts every now and then, just ‘how you doing?’ type thing. There was never any big blowout or anything – no one was rolling around the floor fucking pissed off or something at the end, but something clicked with him – it was actually just a few days before we last came to Australia. We were practicing and maybe I speared off in some kind of weird direction, and he just seemed to think, ‘Maybe I’ve done this enough?’”

Judy’s departure was prior to their last visit to these shores in 2011 – did it impact the Australian tour?

“Yeah, I was a little psychologically fragile feeling because of Eric leaving,” Brock concedes. “Russell [Higbee] – who’s playing bass for us now – he was coming on that trip and it was really fucking serendipitous (or lucky I should say) that he was there at all, because he was just there to play horns on five songs, and we like him so we wanted him to come even though it wasn’t strictly necessary. So when Eric quit, I was like, ‘Shit!’, and I never fucking stop so I was, like, ‘Well man, you reckon you can learn 30 songs or so in the next couple of days?’, and the dude pretty much did it. At the first show we showed up to play I got fucking knackered – for whatever reason I got knackered I don’t know – but I was pretty rambunctious; I’m not sure whether it was stand-up comedy or a fucking rock show.

“But truly and non-butt-lickingly, I fucking love playing Australia. I like Australia – I’ve only hung out on the crust, but the crust is nice! I’m not sure about what goes on 30 miles inland at all – I’m guessing iron mining and a couple of kangaroos – but it’s great there. One of the first times we ever went there I took a week or so afterwards to up to the Great Barrier Reef and around that area, and I was in the ocean and there was no one fucking around, no one on the beach for miles in each direction, and I’m flailing around in there by myself, just going, ‘This is amazing! What’s wrong with these people? Do they not know this exists?’ But the sign that I’d kinda glanced at when I walked down to the shore apparently warned of a crazy box jellyfish eruption right around then and you were not supposed to be in the water. It was the only time in my life – and might be the last time in my life, unless some wonderful very proactive plague hits the planet – when I get to be on a badass beach without a whole bunch of other people. More of that please. Bring on the plague that affects nothing involving me!”

Brock seems entirely unaffected by his band’s recent victories, but on some level was he surprised by the sudden success of Modest Mouse?

“You know, I didn’t really ever think it was on the cards for us, but it’s kinda no more no surprising than 90 percent of the other shit that gets big,” he offers. “That’s what’s shocking! I’m not saying we’re great, but we’re definitely better than 90 percent of that shit. It’s more shocking that there’s not more things like us that are popular. I understand that there’s no way to ever understand properly how these things work, but in one way it’s pretty simple; Top 40 acts like singers who do that soul/yodeling – souldeling – that’s been ever so popular for about 20 years now, that’s easy to control. You don’t have personalities to deal with. You have one person – we’ll call them the tool – to just shove into whatever scenario you need to fill, buy some fucking outfits and shit and just test the water. And if people don’t fucking like it, leave them there and sooner or later people will drink the water.”

Surely it must be a good feeling though having tasted that success without compromising the band’s core aesthetic (despite what some people espouse about Float On) or pandering to the corporate machine?

“It is when people don’t criticise it,” he smiles. “I bet we could figure out how to have another hit, but this is what we enjoy doing. It would be like having Dylan or fucking someone decide that he’s gonna do some rap – it would feel forced or something. I like that we’re still able to do whatever the fuck you call this, and I hope that the next record has no fucking Top 40 appeal whatsoever. You know what, I know a guy – I bet I can make that happen.”