Gaspar Noé is one of cinema’s great provocateurs; a ridiculous maximalist whose orgies of sex, drugs, and violence are some of this century’s most memorable turn-it-up-to-11 movies. The French filmmaker’s five features are not always ‘good’, and watching them is usually deeply unpleasant, but each is utterly audacious, obnoxious, and, in its own way, unforgettable.

1998’s I Stand Alone gives the audience a countdown to avoid its imminent ultraviolence, an on-screen title offering ‘You Have 30 Seconds to Leave the Cinema’; a device that, really, just goads a viewer to stay. 2002’s Irréversible, his collaboration with French cinema royalty Vincent Cassel and Monica Bellucci, is a film told in reverse, its scenes all delivered without cuts; including, most infamously, its harrowing ten-minute rape scene. 2009’s Enter The Void is nominally Noé’s ‘religious’ film, but it features horrible characters, incesty siblings, and motion-sickness-inducing camerawork; effectively out to capture the feeling of being on psychedelic hallucinogens. 2015’s Love is a 3D movie featuring unsimulated sex, its climax being a literal money-shot, in which ejaculate flies out of the screen towards viewers. And, now, here comes Climax, one of cinema’s most singular ‘bad trip’ movies, in which a ’90s dance-party turns into a sustained, depraved nightmare of, of course, sex, drugs, and violence.

The promo poster for Climax, plays on that history, amusingly offering: ‘You Despised I Stand Alone, You Hated Irreversible, You Loathed Enter The Void, You Cursed Love, Now Try Climax’.

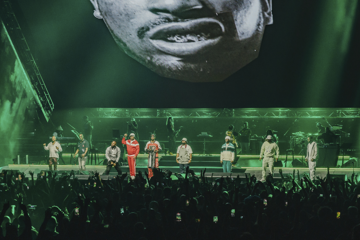

And yet, this time around, something unexpected has occurred: critics and audiences have, largely, loved the film. Set at a lock-in cast party for a dance troupe, and set to an ongoing DJ set, Climax has an abundance of energy, and comes filled with a host of colourful characters, many of them endearing. This endearment has earnt Climax the crown of Noé’s least-hated movie.

"Most people come out of this movie smiling, which is a first for me.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“This movie’s more joyful than the previous ones,” says Noé, 54, on the phone from Paris. “The energy of the dancers, the energy of the camera movement, the energy of the music, it makes the movie —for the first half, at least— something that’s really energetic, exciting. Most people come out of this movie smiling, which is a first for me.”

Noé feels strange that this has happened, but he’s also fine with it. Contrary to his reputation, and the reception to his films, he claims he’s not out to provoke people; and hates being called a provocateur. “I don’t like this term, provocateur,” Noé spits, French accent thick. “Someone who is out to provoke people is like some guy on the street who spits on people, hoping that someone will eventually smash him. It’s some drunk person, someone silly, who’s making irritating noises at the bar. I’m not out to provoke. I’m just out to make movies that I like.”

Full of sexual energy, self-destructive excess, and manic energy, Noé’s films are usually about young people, and play to young crowds. This is, he explains, because he conceived of the vague concepts for the films —for Enter The Void, Love, and Climax— back when he was young, dreaming of making the kind of movies no one has. Even now, Noé admits, his goal is to make something “that if the teenage me had watched them, on video, they would have blown his mind.”

“My movies aren’t the same as everyone else’s,” Noé says, with a hint of pride. “But that says something, to me, about expressing yourself the way you want to. Making the kind of movies I do, that’s something I’m able to. It’s probably harder if you’re just making the latest episode in a franchise.”

The initial concept for Climax wasn’t to make a dance-movie. “I’m not attracted to contemporary dance at all,” Noé says, dismissively. “But I loved the way these dancers danced, and I knew there was something innately cinematic to set such a story among dancers. If you go to a party, or to a club, and you see this kind of dance on the dancefloor, you’re hypnotised. You stop dancing yourself, and you just start watching.”

Instead, his first idea was to make a film “about a group of people turning crazy and destroying everything they’ve constructed.” In practice, that means that Climax is a film divided. Its opening half is full of giddy, joyous dancing, until someone spikes the celebratory sangria with a dose of bad acid, and the whole film turns into a bad trip; a long, disorienting nightmare that —literally, via a visual device— flips the film on its head. Noé films these sequences with a steadicam, moving through the crowd. Initially he’d hoped to make the film as but “two long master-shots of 45 minutes”; a dream that didn’t quite hold, but plays out on screen.

"I said to my producers: I want to put the credits right in the middle of the film. To which they said: ‘Gaspar, shut up, nobody does that’."

“I wanted each part of the film to feel separate from the other,” Noé offers. “[Stanley Kubrick’s] Full Metal Jacket was like that, it had this divided two-part structure. You have the preparations for war, and then you have war itself. With [Climax], the first half was to be exhilarating and joyful, and the second part it’s all falling down. I always try to find ideas that you haven’t seen on screen before. So, when I needed some way to get from the first to the second, to separate the beginning from what comes after, I said to my producers: I want to put the credits right in the middle of the film. To which they said: ‘Gaspar, shut up, nobody does that’. After that, I knew that the credits had to come in the middle.”

Arriving mid-way as division point, the electric, exhilarating credits for Climax —cut to the acidic thunk of What To Do, an aggressive 1995 house banger from Noé’s longtime musical collaborateur, Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk— are another example of Noé as cinema’s greatest artist of the credits sequence. They bring back memories of the Enter The Void credit sequence, which Quentin Tarantino, himself a proponent of artful credits, called “one of the greatest in cinema history”.

“I used to like the credits sequences before the ’70s, because there wasn’t this ending credit reel, there was just the opening credits,” explains Noé. “And the graphic designer could just concentrate on 40 names, 50 names. Now, you have thousands of names in the movie, so you just have this endless roll of names at the end, which is incredibly boring. I wish I could do movies with just two or three panels of names. But, contractually, you have to respect the work of everyone involved in the production.

“So, I’ve just thought of a way of trying to make that as interesting, and alive, as possible. To me, [a credit sequence] works so much better as a prologue than an epilogue. I’m surprised more people don’t try different things like this. This is the problem with movies these days, people just do the most generic things all the time. I really wish people would try to have more fun with things like this.”

Noé and Bangalter had plenty of fun assembling the playlist for Climax, which includes everything from M/A/R/R/S’ Pump Up The Volume to Soft Cell’s Tainted Love to Aphex Twin’s eternal Windowlicker. “We wanted the most danceable music from before 1995,” Noé says. “We wanted to get the instrumental versions of tracks, so that the dancers could improvise to the rhythms of the tracks without having to navigate the words of the songs. So, we found an instrumental version of [Patrick Hernandez’s] Born To Be Alive, we found an instrumental version of Supernature by Cerrone. We negotiated the rights to all the songs before we started filming, so that the dancers would be dancing to the actual music that we were going to use.”

Where Bangalter had composed the scores for Irréversible and Enter The Void, here —in a film with no score, only played records— he did something different: offering up old compositions for use, even including a climactic, new-age-turned-terrifying track that takes pride of place in the picture. “Initially I asked [Bangalter] for some instrumental versions of 1990s tracks,” Noé says. “And he said to me ‘Oh, I have this track that I made in 1995 that was never released’. It has no name, and, now, it’s called Sangria. I couldn’t believe it had never come out. It fit the movie exactly, and it was incredible.”

The song arrives when Climax is operating at peak depravity; as the troupe of dancers have turned on each other, on themselves, the whole thing turning deeply unsettling. Once again, it’s another Noé film out to take the audiences to uncomfortable places; to put viewers through a wringer via dark ideas and vivid mise-en-scène. Noé sees the film —and all his films— as essentially experiential, cinematic events that people suffer through more than just popcorn entertainments. If it’s horrifying to watch, then it’s working.

“[Climax] is a kind of horror-movie,” says Noé. “You want people to writhe, to scream, to feel fear and anxiety. When you’re making this kind of movie, you’re constructing a rollercoaster. Of course, you do this to elicit reactions from the audience. You can’t be coy with this kind of thing.”

“A movie is like a shamanic trip,” Noé continues, in a very Noé-ish way. “When it’s good, it’s transcendent, you forget who you are and where you are. But, when [a movie’s] dull, it’s just like going to the restroom. I like movies that are like shamanic trips. It’s like when you go to see the shaman, he turns out the lights, he puts some mushrooms in your mouth, and then you’re tripping out for 90 minutes. Nothing happens to you, but all these visions fill your head. If you see a movie like 2001, Kubrick puts the movie as if it’s in your eyes, and you feel like you’re tripping out for 140 minutes. When cinema is at its best, it’s like one long trip, for the duration of the movie. Only without any consequences or unexpected side-effects.”

Climax hits cinemas across the country on 6 December