THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES

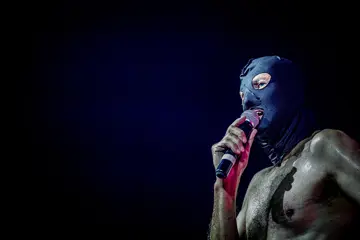

Russell Brand is pissed off. Free Market Fundamentalism, Wall St. bail-outs, financial sector fraud, oppressive corporate oligarchy, ever-widening social inequality, the neo-feudalist exploitation of the many by the privileged few, the persecution of dissidents and whistleblowers whilst the criminals operating on massive scale (finance, military, etc) get away scott-free... the world is fucked.

And, as The Emperor’s New Clothes happily cops to: Brand, himself, is winning in this hideous system. He is, literally, in the 1%. And if he is pissed off, what does that say about the rest of us? Why have the 99%, seven years after the global financial meltdown, returned to quiet servitude?

Directed by Michael Winterbottom, The Emperor’s New Clothes is an impassioned polemic; a piece of Michael Moore-inspired monkeyshines that doubles as a howl of outrage. It’s both a chastening of our collective complicity in the dystopia of new-millennial life, and a call to arms: a relentless poking at the gobsmacking inequality that is business-as-usual on a hyper-capitalist planet, delivered with insouciance and indignation.

“You already know all this,” Brand says, at the start, in the first of his many to-camera monologues; both flattering and critiquing those sitting down to watch the film. Brand has a host of crowdpleasing tricks to bring the absurdity and injustice of modern society to light: an assembly of 100 kids representing a percentage of the world’s population, with wealth divided unequally between them; quality time spent with struggling families and those on disability who exist on an urban poverty-line; doorstopping show-ups in the foyers of British banks and the houses of the lordly and fraudulent.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Brand has abundant charisma, the common-man touch, and the celebrity platform to bring publicity to what is, essentially, a desire for dissidence, civil disobedience, and an imminent uprising. Where more-respectful, Sundance-style documentaries present a measured, hope-tinged, ‘inspirational’ approach to their The-World-Is-Fucked documentaries, Brand is all swagger and snarl, spit and bile, blood set to boil. His approach is subtle as a sledge-hammer, but, here, that seems more plaudit than criticism. When our collective humanity is being buried under a system erected so wealth consolidates in the hands of the privileged few — 80 people possessing the same as 4 billion others — the time for politeness is long gone.

ALOHA

The times they are a-changin’. That’s an apt cliché to employ —given its status in Baby Boomer rock’n’roll lore— to the career of Cameron Crowe, one-time Hollywood Golden Boy turned critical punching bag. His latest film, Aloha, has been mocked from hither to yon, criticised for cinematic whitewashing and employing Hawaii as a fecund, fertile land in which to exercise your white male privilege. It’s been called a symbol of Crowe’s downward spiral, lambasted as an unmitigated disaster. But here’s the thing: it plays almost exactly like Jerry Maguire; is, in many ways, a more interesting, ambitious, conflicted film. To claim that one was a paragon of rom-com magic and this latest is a horror-show seems somewhere between disingenuous and delusional; it’s not the director who’s changed, but audiences.

Here, Crowe gives us another smarmy, charismatic, alpha-male prick (Bradley Cooper, essentially channelling Tom Cruise) fallen on hard times; then hands him another Manic Pixie Love Interest (Emma Stone) to turn that frown upside-down. The leading-man has been phoning in life for years, being a mercenary, taking the cheque. But, on a last-chance, make-good military-business trip to ethnically-exoticised Hawaii, a series of moral choices come along with which he can put things right.

To just fuck the girl, or actually commit to something? To swallow your own culpability in hyper-capitalist corporate rule, and do the illegal bidding of a lawless billionaire (Bill Murray!), or put morals above money? To abet in the exploitation of Hawaiian land at the expense of its native peoples, or to make your sales-rhetoric promises mean something? To face up to the ex-girlfriend (Rachel McAdams) you once fucked over, and pay an emotional penance for the wreckage (and possible paternal heritage) you left in your wake, or just run away, like you always do!?

Spoiler alert: the heroic white male saves the day, and gets the girl, the gift of a daughter he didn’t have to bother to raise, and the respect of real-life Hawaiian indigenous-rights activist Dennis ‘Bumpy’ Kanahele. Even as Crowe lays on the wild sentimentalism and emboldens the creakiest rom-com clichés as if dramatic profundity, he winkingly acknowledges the essentially cynical nature of the enterprise: Stone talking about Cooper’s deep blue eyes and sly smirks and three-day stubble even as, as audience, you’re supposed to be in thrall to them.

Crowe is, as ever, a director of movie-stars, and Aloha leans heavily on their charisma. Cooper bats his baby-blues; Stone plays her ultra-eager, super-sincere military terrier with as much enthusiasm as it’s written; Alec Baldwin does some great Jack Donaghy scenery-chewing as rage-filled military brass; and McAdams makes her role feel lived-in, warm, human: when she smiles, teeth gleaming white, Crowe knows how to make it light up the whole screen. Hollywood has, forever, produced filmed entertainments that do just this: serve up morally-questionable premises and ultra-contrived scenarios that, thanks to the attractiveness of those on screen, are swallowed by audiences; sugared pills laced with the kind of sentimental treacle the never-subtle Crowe is ever happy to drizzle over his dramas.

But, this time, apparently, Aloha cannot be stomached. As someone who’s always hated Crowe’s films —the Gen X stereotype-forging of Singles, the horrifying ‘cute kid’ hijinks of Jerry Maguire, the masturbatory rockist nostalgia of the repulsive Almost Famous, the Orlando Bloom of Elizabethtown, the poor-middle-aged-male-works-through-grief-by-fucking-Scarlett-Johansson fantasia of We Bought A Zoo, the career-long love of Pearl Jam’s dreadful music— the prospect of people turning on him, and the world passing him by, should be heartening.

But, instead, the scorn poured upon Aloha feels ill-deserved; somewhere between a backswinging market-correction and a snowballing mob-mentality. From the moment it was slandered by its own studio in the Sony leaks (back in those misty days when it was just Untitled Cameron Crowe Project), it’s been a lamb lead to the slaughter; a ‘bomb’ that comes pre-tagged, no thought needed to lay in on it. And when it came out that Stone’s character was supposed to be a quarter Asian, the internet went into Collective Outrage hysteria; humans apparently caring more, now, about policing shitty-movie casting ethnicity on the internet more than genuine social activism. This isn’t to say that Aloha is great, because it’s surely not; but take every ‘Cameron Crowe has lost it!’ condemnation with a large grain of salt. The outraged zealousness of all those arriving late to this conclusion only makes them look bad. He never had it in the first place.

TOMORROWLAND

“When I was a kid, the future was different,” says George Clooney, intoning aloud the essential theme of Tomorrowland. Disney’s mega-budget sci-fi extravaganza is, in theory, aimed at an audience of kids (and, with Britt Robertson and Raffey Cassidy in lead roles, an audience that actually includes girls); Brad Bird’s film stoking that old cinematic flame, of the theatre as a temple, a sacrosanct place in which an impressionable young mind can dare to dream. But it’s also a film built on Baby Boomer nostalgia; an old-man’s lament not for the lack of jetpacks and moon colonies in contemporary life, but for our bleak shared vision of humanity’s future. And, in turn, the current state of science-fiction.

Sci-fi was once the paragon of daydreamers and visionaries, who imagined wild inventions and interplanetary expeditions, boldly forging forth into a foretold future of human achievement and boy’s-own derring-do. But with space —that final frontier— now seeming more and more like an endless wasteland, an abyss without end, writers have their gaze back to Earth; and our collective portraits of this planet’s future are uniformly dystopian, the natural product of a life on a rock growing hotter, more toxic, more crowded, more Orwellian with each lap of the sun.

Like Matthew McConaughey’s space-cowboy in Interstellar, Bird isn’t out to accept our sad fate; wants, once more, to look to the stars, to dream big. The director —aided by Lost boffin Damien Lindelof— marshals symbols of the Better Living Through Chemistry Era: the 1964 World’s Fair, the Disneyland ride on which the movie’s based, the retrofuturist kitsch of Buck Rogers. He conjures its titular place not as dystopia, but utopia: a Magic kingdom of multi-level swimming pools, wacky fashion, and rockets to the moon. This vision of the future is so hopeful that it essentially apes the visual language of advertisements: it full of the glittery promise and aw-shucks all-togetherness of college brochures or development-property pamphlets; anything else offering us the promise of a better future.

It’s this future into which Robertson’s optimistic dreamer and Clooney’s pessimistic curmudgeon voyage, with some kind of evil people blowing stuff up on their trail and all manner of ticking-clock countdowns near climax. The story doesn’t quite stick, the chases feel unnecessary, and the sense of dread non-existent. Bird cut his teeth in animation —and went on to direct The Iron Giant, The Incredibles, and Ratatouille, quite the three-film run— and Tomorrowland, with all its Jetsonian retrofuturism, essentially plays as a live-action cartoon: bright and colourful and silly, and completely unmoored from reality. Rather than reflecting the ills of our contemporary society, it’s an exercise in genre nostalgia whose essential message —dream big— not only sounds like an ad slogan, but carries the same weight.

STRANGERLAND

Strangerland marks the first time Nicole Kidman has been the lead in an Australian independent film since Dead Calm, the 1989 thriller that turned her into a star, and lead her into the arms of Tom Cruise. And she’s back with all guns blazing, submitting one of those raw-and-wounded turns that, when you’re an actress —and an older actress, especially— get called ‘brave’. Here she cries, wails, screams at the heavens, wields her sexuality like a weapon, loses her shit, her mind, and her clothes; walking down what passes for Main Street in the film’s one-horse town totally naked, smeared in blood, lost in delusion.

Here, she’s descended into the depths of twin parental-anxiety nightmares: 1) her kids have disappeared into that primal furnace of the outback; and 2) even worse, her daughter is the local tart! Where Kidman’s turn in 2010’s questionable Rabbit Hole found her grieving turned into a study of survival-mechanism repression, domestic bickering, and an unexpected comedy-of-manners, here things are far more primal, more sexual.

When Strangerland begins, Kidman, husband Joseph Fiennes, and resentful kids Maddison Brown and Nicholas Hamilton have just relocated to this “shithole of a town”, an Outback outpost their blonde-haired, blue-eyed kids look ill-suited for. They’ve moved hoping for a fresh start after things’ve gone bad, the exact circumstances of their past carefully meted-out by Fiona Seres and Michael Kinirons’ script. But immediately we’re introduced to their greatest problem: that Brown will fuck anything that moves. Were she a son, it’d be a noble trait; but, here, it’s Every Parents Worst Nightmare. Well, that and the fact that, in the first act, she and her brother vanish without a trace into the unforgiving landscape, tapping into the terror of the outback’s endless expanses, a place people vanish into.

And this is where Strangerland gets problematic. Its writers and director Kim Farrant have interesting ideas about, say, colonial privilege and the exoticisation of Native mysticism, in the sexual guilt and repression of a father confronted with a sexpot daughter, and in the way a tragedy —or, at least, the appearance of one— can tap into the primal emotions normally kept behind the façade of polite society. But they also banish a girl into the wilderness —to likely death— and then have their characters claim she had it coming to her; that any promiscuous 15-year-old girl is on a path to sure self-destruction. Here, the tragedy of the slutty daughter is given as much wait as the tragedy of the missing kids, making Strangerland play like a piece of cinematic slut-shaming.

MARSHLAND

Marshland has been compared to both True Detective and Zodiac, lofty comparisons that it can’t really hope to measure up to. What such evocations are really out to evoke is this: in 1980, a pair of moustachioed, self-destructive cops are investigating a murder-case in a period-era backwater; and obsessive-sleuthing, mounting tension, and gleeful period wardrobe all ensue. The original-odd-couple cops, Raúl Arévalo and Javier Gutiérrez must navigate both their moustaches and their personal demons, as they’re on track of a killer targeting young girls, whilst under the hostile eye of locals who resent these big-city interlopers coming down from Seville and poking around in their business.

This set-up is pure cliché, but like the best procedurals, as Marshland digs deeper into the case, it sinks further into the local milieu. The marshes of the Guadalquivir river are, of course, a fantastic noir-movie symbol; a moral quicksand that swallows up lost souls, buries secrets. And though Alberto Rodríguez’s direction may lack the precision of David Fincher or Carey Fukunaga, it doesn’t lack the ambition: often turning to eye-of-God overheads of the river and its swamplands, positioning the viewer above the fray, before descending deep into it.

Its period setting proves, too, to be not just an excuse for wide-collared open-neck shirts and aviator sunglasses, but suggestive of a deeper theme. It’s set in the wake of Franco’s death, in the nascent days of a new democracy; giving its buried secrets —and bodies— real symbolic weight.