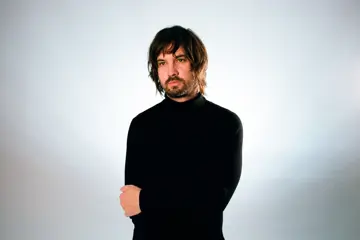

Bloc Party

Bloc PartyFour is a neat album. For all Bloc Party's sinewy instrumentation and nervous energy, they've never been a band of restraint. 2008's divisive Intimacy threw everything from dubstep breakbeats to choral arrangements at a listener. 2007's A Weekend In The City was effectively a concept album. Even their 2005 debut, Silent Alarm, was almost overloaded with ideas. Four, though - Four is different.

It's tight. Economical. The band's eclecticism remains - Octopus's mangled guitar hook, for example, followed by banjo-led melodies in Real Talk - but there's a sense of liveliness that undercuts even their most ambitious excursions. It's telling that, in recording the album, the band opted for neither of their previous producers but Alex Newport, a man perhaps best known for his work on Sepultura frontman Max Cavalera's industrial-metal Nailbomb project.

“The only discussion that we had about the musical direction of it was, when we got together at the end of 2010 to discuss what we were going to do with Bloc Party, I said 'If we're going to make another Bloc Party record, I think it should be the sound of the four of us in a room together - or as close to that as possible,'” frontman Kele Okereke says of the record. “I think all of our previous records have been quite studio-based records.

“You know, from Silent Alarm through to Intimacy, we've kind of written our songs and then figured out how to play them live. This one's quite a bit leaner. In recording it, we knew we didn't want a producer - someone who would craft the album. We wanted more of an engineer - someone who would just document the sound. I remember listening to Alex's showreel and being very impressed by his restraint and his detail.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Critics have already been quick to explain the record's direction with a variety of theories, most popularly positing it as a reaction to the electronic experimentation of Intimacy. More ambitious critics have drawn a line from Intimacy through the band's year-long hiatus and Okereke's equally electronic 2010 solo album, The Boxer, suggesting Bloc Party's remaining members had become oppressed by Okereke and that Four is his apology.

“There's no validity to that idea at all,” the frontman says in response, his tone seemingly pitched halfway between annoyance and amusement. “Without wanting to talk too much about our internal writing processes, I can categorically state that that was never the case. I certainly don't see Intimacy as any kind of disaster. I see it as being part of our back catalogue. I see it in the same way as Silent Alarm or Weekend In The City.

“I look at it in the same way that I'll most likely look at Four once this touring cycle as finished - it was part of our journey as a band. When I look back at any of our previous records, I hear things I'd like to have redone. I hear things we didn't get quite right. You know, I have that trouble with our first album. For a period there, I couldn't listen to it at all because I just heard all the things that weren't right about it.

“Still, I feel they're all steps on our journey and I think of them all in the same way. You know, listening back to Intimacy, I still think it has some of our best work on it. It has some of our best songs. I think it has some of my best lyrics. So, really, I actually feel quite fond of that record. I don't think of it as any kind of disaster or missed opportunity or anything of the sort.”

Speaking to Okereke, one begins to suspect Four is representative of a much larger shift. Bloc Party have always led a surprisingly complicated existence. The slightest remark from Okereke can lead to any number of controversies and rumours. Most recently, an offhand comment in a triple j interview led fans to believe Four would be the band's final album. (Not the case, as Okereke later clarified.)

“Well, it's nice to know people are listening,” the vocalist reflects diplomatically of his relationship with the press which, all too recently, also gave rise to the rumour that he had been kicked out of his own band. “It's nice to know that you can reach people and there are people out there interested in what you do. I'm not going to lie, though - I have always generally been quite suspicious of the media.”

Musically, their output has been similarly complex. Given that their initial rise to fame was in no small part predicated on their kinship to classic British post-punk and indie-rock, their sound has showcased an unbelievable scope of influences over the years from elements of grunge, new wave and pop through to aspects of dubstep, garage, grime and hip hop. Four actually seems to reference heavy metal on occasion.

“When we started making music together, we were very much bonded by a dislike of what was happening around us at the time. When we started this band, the bands that were popular in the UK were bands like Travis and Starsailor. Real kind of namby-pamby, acoustic singer-songwriter bands. We just wanted to make something with a sense of energy. That's the only thing I remember wanting to do at the time.

“In terms of specific sounds, I'm not sure there ever really was one. One of the clubs that we went to that was one of the biggest influences for us and how we think about genre was this club called Trash. Defunct now, sadly. It was quite instrumental for us as a band because you'd go to this club and hear Joy Division mixed with Madonna mixed with Missy Elliot mixed with Nine Inch Nails.

“You'd hear all this music from very disparate places in popular culture - but they were coming together and working together because it was good. It was good music. I learnt then that genre isn't something to define you. It's something to rail against. It's not something I want to be part of. I want people to see I'm as into the Deftones as I am Squarepusher as I am Nicki Minaj as I am Blur.

“You know, I think we've always tried to distance ourselves from other bands. I can remember in 2005, we were supposedly a part of this British Invasion of bands - that we didn't really know as people or we weren't really fans of their music. Wherever we went, we always found ourselves lumped in with that group. And I think, to be honest, we've always tried to fight against that.”

Four doesn't seem so much a reaction to Bloc Party's previous album. Bloc Party's hiatus seems, in retrospect, a reaction to their career, from an industry that forced them to prematurely churn out a third album, to a media more interested in Okereke's personal life than music (he came out as gay in 2010), to their own inconveniently expansive ambition; Bloc Party's career has always been complicated.

No longer. The band refuse to tour for more than three weeks at a time. In conversation, Okereke is cordial but guarded (see sidebar). While he will not rule out a fifth Bloc Party album, he is similarly circumspect about committing to one. Having spent their career at the mercy of others, Bloc Party seem to have recently become determined to live by their own terms. And that, more so than anything else, is the sound of Four.

“I do think about Bloc Party's future. I do think about it, for sure,” Okereke admits. “But part of the problem that we had at the end of 2009 was that we felt that our lives were simply going from one year-long world tour and then straight into the studio to make a record and then back out into the world to tour that record. You know, you can only do so much of that before the situation starts to feel a little bit toxic.

“You know, you start to find it hard to figure out how to have a life outside of what you do for a living. I think we're all a bit wary of rushing back into that routine, into that rhythm, because it was quite destructive. “Creatively, right now I've got no idea what another Bloc Party record would sound like right now - but that's a good thing. I think that's a good thing. We're ready and willing to be inspired - and I'm sure that will happen over the next year.”

“But,” the frontman stresses, “that's a conversation we would need to have between us - whether we actually want to go through it again. One of the good things I learnt about taking that time out - having six months of not doing anything in particular and just taking time to breathe, is a good thing. It's very important. You know, none of us need Bloc Party. If we stopped, we'd all be fine. We don't need to do this.

“That actually takes the pressure off, though,” Okereke adds. “I know that, if we do make another record, it will only be because we want to. I just don't think we'll know if we want to go through that again until the end of this year.”