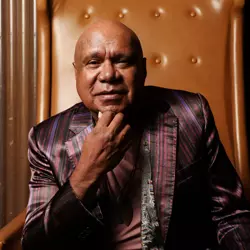

Archie Roach

Archie Roach“One of the most beautiful love stories Australia’s ever heard.”

Family was everything to Archie Roach. The most heartbreaking story he told me over the course of several interviews was when I mentioned his friendship with Goanna singer Shane Howard.

Shane and Archie hailed from the same country, just outside of Warrnambool on the south-western coast of Victoria, the land of the Gunditjmara people. They were born just a year apart but didn’t meet until the late ’80s.

Archie smiled when he told me that Shane’s father had known his dad. In just three simple sentences, Archie conveyed the tragedy of the Stolen Generations. “I met Mr Howard a couple of times and we had a yarn about my dad,” he said softly. “He said my dad was a thorough gentleman. That meant a lot to me.”

Of course, Archie never got to know his dad, Archie Roach Sr. Young Archie was just three when he was taken from his parents and raised by a Scottish couple, Alex and Dulcie Cox.

As Archie Cox, he was a student at Lilydale High School when he received a letter from his sister Myrtle, informing him that their mother had died and he had four sisters and two brothers. It was addressed to “Archie Roach” – that’s how Archie discovered his real name. Archie told his teachers he didn’t want to be called Archie Cox anymore. Not long after, he “took off”, in search of family and his identity, with just his guitar to keep him company.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

In Adelaide, Archie met another homeless teenager, Ruby Hunter, who was also part of the Stolen Generations. When she was eight, a group of men arrived and told Ruby and her siblings they were taking them to the circus. They ended up in foster homes instead.

“I couldn’t believe how close Ruby’s story was to mine,” Archie would later write in his autobiography Tell Me Why. “I thought it was only us in Victoria who were taken away from our families. But that wasn’t the case.”

Archie wrote about meeting Ruby – a Ngarrindjeri woman, from the Riverland in South Australia – in the song Old So & So, a “young vagabond” meeting “this princess”, recalling how “she could not stop talking”.

“I wanted to be close to her wherever we went. I was fascinated by Ruby and felt comfortable around her, and even though I was a quiet person and didn’t talk much, I could talk to her. She never seemed to tire of my company.”

In his memoir How To Make Gravy, Paul Kelly described Ruby as a “small, cheeky woman from the Riverland” with a “cackling laugh”. Fifteen years after Archie and Ruby met, Paul and his guitarist Steve Connolly would visit their house in East Preston and sing together around the kitchen table. About a month into these sessions, Ruby prompted Archie: “Play that Charcoal Lane song.”

“The hairs stood up on my neck again as he took his guitar and sang about his drinking days in the back lanes of Fitzroy, before he and Ruby got sober,” Kelly remembers. “A song, I thought to myself at the time, Richard Thompson would kill for.”

Paul Simon would also visit Archie and Ruby’s modest home when he toured Australia in 1991. Archie’s manager told him, “Paul Simon really admires your work and he’d like to meet you.” Archie was aghast when Ruby served Simon ham sandwiches, unaware of his Jewish faith. “Mum! Mum!” Archie said. But Simon smiled and replied, “It’s okay, I’m not orthodox.”

I met Archie when he released his debut album, Charcoal Lane – produced by Paul Kelly and Steve Connolly – in 1990. I traipsed up the stairs at Mushroom’s headquarters in Dundas Lane, Albert Park, where I was greeted by Archie and a woman in the boardroom.

“This is Ruby,” Archie said.

I soon realised that though it was just Archie’s name on the cover, this was very much a partnership. As Clinton Walker put it in his seminal text Buried Country, “Together, Archie and Ruby – well, it’s almost impossible to imagine one without the other. They were more than soulmates in life and music, they were part of – the heart of – an organism much larger than just the two of them.”

“When Archie writes a song, I’m always the first person to hear it,” Ruby told me that day. “That’s an honour.”

When I mentioned that Down City Streets was a highlight of the album, Archie proudly responded: “That’s Ruby’s song.”

“Most of my writing is influenced by Archie’s style of writing,” Ruby explained. “They are the same stories, but I’m singing about the woman’s struggle – the black woman’s struggle.”

Ruby laughed when I asked if she planned to make her own album. “That’s just a dream,” she said. “At the moment, I’m trooping around with Archie.”

But after the success of Charcoal Lane, Mushroom Records offered Ruby her own recording contract. Archie said, “Mum, I reckon you’ll be the first Aboriginal woman to sign with a major label.”

“About time,” Ruby replied.

Ruby released her debut album, Thoughts Within, in 1994.

When Archie wrote a love song, it was for and about Ruby. It wasn’t always an easy road, as Archie documented in From Paradise:

“She met a boy who kind of knew,” Archie sang, “some of the things that she was going through. But he was confused, so he ran away. She found him again and here she is today.”

As the ABC’s Indigenous Affairs reporter Bridget Brennan put it, Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter were “one of the most beautiful love stories Australia’s ever heard.”

A former bandmate of Archie’s told me that Ruby “was a tough little lady – she ran the house”. When I met Archie and Ruby, they had two kids of their own – Amos and Eban – and seven foster children. “Yeah, it’s pretty busy,” Ruby said matter-of-factly.

Ruby would later tell Clinton Walker, “Family is very important to us. Family and music – that’s what held us together.”

Archie and Ruby’s story was the subject of Philippa Bateman’s recent documentary Wash My Soul In The River’s Flow. “Archie is my silent hero and I’m his rowdy troublemaker,” Ruby said in the film.

Archie’s world changed forever in February 2010 when Ruby died at home after suffering a heart attack, aged 54. “Nothing meant anything after losing Ruby,” he said. But then, Archie started hearing Ruby’s voice: “You have to pull yourself together, Archie Roach. There are important things for you to do.”

The following month, Archie managed to honour his booking at the Port Fairy Folk Festival, where he was joined on stage by his old friend Shane Howard. Archie told the crowd he needed them “to help me pay tribute to a beautiful lady who has touched so many hearts, but most of all mine”.

One crowd member yelled, “We’re with you, Archie!”

“This is exactly where I needed to be,” Archie reflected, “connected to the very people who had known both Ruby and me for years and years, through our songs and seeing us perform live together.

“They were family, too, and today we needed to grieve together.”

In that 1990 interview, I asked Archie who he wanted to hear his songs – white fellas or his Indigenous brothers and sisters. It was an awkwardly phrased question, but Archie didn’t take offence. “Everybody,” he smiled. “I’m trying to get people together, not just our own people. If only we can get to that place of healing, we can do great things together.”

Archie Roach died, aged 66, surrounded by family, in the Warrnambool Base Hospital last Saturday. As Bridget Brennan noted, “He’s with Ruby now.”

READ: ELEVEN ARCHIE ROACH MUSICAL MOMENTS WE WILL NEVER FORGET