Soul Asylum

Soul AsylumIt's been a strange but incredibly fascinating career arc for Minneapolis-bred rock veterans Soul Asylum. They kicked off all the way back in 1981 under the name Loud Fast Rules, but the by the time they'd changed their name to Soul Asylum a couple of years later their abrasive rock had already made a deep impression around local traps, a scene dominated by the massive twin peaks of The Replacements and Hüsker Dü.

For years they remained in the shadows of those underground behemoths – forging a career and a solid reputation but basically existing in the fringes – until suddenly in 1992 their sixth album Grave Dancer's Union exploded (mainly due to single Runaway Train tapping into some weird grunge-obsessed zeitgeist) and they were suddenly a massive commercial entity, playing at US President Bill Clinton's inauguration and enjoying all of the trappings of commercial success.

Few had expected Soul Asylum to be the band from their clique to break into the big time, and the band themselves struggled with their newfound fame – they spent the next few years trying unsuccessfully to emulate that success, with varying results. Now, some two decades after their career peak, they're back with their tenth album Delayed Reaction – their first in six years – and, having returned to the indie realm far away from the pressure of the major label world, a whole new way of looking at their craft.

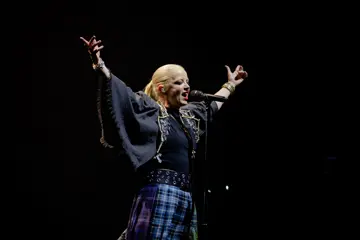

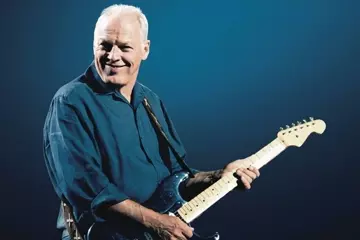

“I pushed the record, as far as doing a lot of it on my own incentive and doing things in a way that it had to be good enough for Soul Asylum, but it had to be done without some of the spoils that the band has had in the past – ie. cash,” laughs frontman and songwriter David Pirner. “So in that regard I'm pretty proud of the record, and I'm also just really trying to understand what it's going to take to make it work in this day and age and with this band, because the band has gotten better, but the band has also gotten... well we're not 18 any more, but driving after the show in the middle of nowhere just reminds me of exactly what we were doing when we were 18. It's either a labour of love or a labour of lust, definitely a labour of something...”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

These days Pirner is crafting his songs to appease his band rather than radio heads or TV execs, and he seems quite content harbouring these far more humble aspirations. “I've never had any other method than no method at all, and the outcome just sorta has to satisfy the constituency, which basically means that I have to write music which is good enough for the band to want to commit it to a recording,” he continues. “It was very difficult because I sort of had to really bring ideas to the band that were completely realisable without having to do a whole lot of fucking around on the part of, 'Let's get all of the band in a room together', because we all live in different places now, and all sorts of complications like that. So just sort of keeping the show on the road is I guess the goal of making an album, as opposed to, 'Hey man, I'm going to go and sell a billion records!' I think it's more of a life-sustaining thing, and the game is survival.”

The success of Grave Dancer's Union came at the height of the grunge explosion when majors were looking to the underground as a new way to print money, and while Soul Asylum definitely played the fame game – Pirner dating Winona Ryder, even scoring a cameo in her flick Reality Bites – he claims that this success was inadvertent rather than something they chased.

“I think probably as far as being a commercial entity, that was never really the band's intention,” he posits. “It's helped by opening a lot of doors and getting the band into studios where it became more of an education, in terms of, 'We've not got a bunch of money to make a record, and I'm going to learn everything I can from these producers and engineers that we can now afford', and theoretically in my mind I have learned from these experiences. But I think as far as trying to recapture anything, that's not really what we're trying to do. We're trying to carry on whatever it is that makes the band great, and that's the hardest part to maintain. I'm totally thankful for whatever it is that's enabled us to survive, and for better or worse that album helped us survive.”

Naturally Pirner has fond recollections of the early days, when Soul Asylum played a small but pivotal role in what would become one of the most influential scenes in the history of underground music, still feeling a bond with those bands that were around him at the time (The Replacements' Tommy Stinson is even Soul Asyum's current bassist).

“I think there's such a weird retrospective look at the way that things turned out,” he muses. “Back during those days it was really us against the world and all that sort of shit, [us and] bands like Hüsker Dü and The Replacements and all the SST bands – The Meat Puppets are a band that I still hang out with. But at the time we were the underground, creating something called 'alternative music' when 'alternative' meant the 'alternative to popular', or 'alternative to something that makes money', or 'alternative to these strange trappings that turn people's view of music and art into something else, depending on how many other people know about it'. So to a degree I think that we were sort of this weird link, and I think when people try to decipher the key element it really goes way beyond, 'Who's cooler, Hüsker Dü or The Replacements?', or 'What if Kurt Cobain had never shown up?' – all these things that people can't figure out are the things that made it so magical.

“It seemed like a whole bunch of bands trying to make this sound and then finally coming into their own, so for these bands who had been out there doing the legwork and spending years and years on the road by the time Nirvana became popular, there was this meeting of the present and where music was going, and it all came together and was a good thing for everyone involved – people acknowledged punk rock for whatever reason, even if it became something that people hated. The stereotypes and clichés are all there – it got oversaturated and overplayed and all that, which seemed kinda gross – but it's very hard to pinpoint when the pursuit became something that we were actually doing. It was an exciting time, and I think in the end I can only hope to be part of this fibre where music is music and it means something different to everybody, but I definitely feel a brotherhood with the people that I grew up with.”