Max Richter

Max RichterMax Richter is one of the few modern composers equally at home on Pitchfork’s Best New Music page and piped through some surround sound-optimised Bang & Olufsen speakers in a Bentley in Kew.

Best known to those who don’t follow post-minimalist composers as “that guy who does the concert you sleep at”, Richter is a composer who most people have heard at some point. You might not know the name of his best-known piece, On The Nature Of Daylight, but you or someone you know has probably wept to it while watching the films Arrival, Disconnect, The Trip or Shutter Island or the television series The Leftovers, The Handmaids Tale or The Last Of Us where it accompanied a climactic scene of loss and despair. On The Nature Of Daylight is a highlight from his 2004 album, The Blue Notebooks, which forms the second half of tonight’s show. First, a sold-out Hamer Hall quietens itself to experience Richter’s 2024 album In A Landscape.

After a lengthy introduction of electronic loops and incongruous puffs of dry ice that linger around the back of the stage as they drift in from a nearby production of Never Have I Ever, the ensemble arrives. Cellist and Artistic Director Clarice Jensen, violinists Ben Russell and Laura Lutzke, viola player Kyle Miller and cellist Claire Bryant.

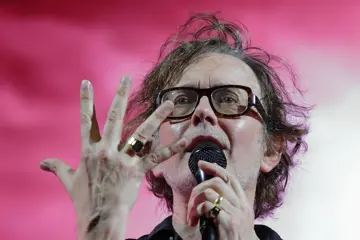

Behind them strides Richter himself, politely waving to the crowd, somehow pulling off a clothing ensemble of his own that combines a black hoodie under a black suit jacket. His grand piano sits stage left, facing away from the audience, while his laptop, effects, and synthesizer face the musicians. Chairs and illuminated music stands, their manuscripts poised, await the performance.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“In this music, you get composed music, found objects, acoustic music, electronic music,” Richter says. “The human world and the natural world. The landscape out there and the landscape we all carry inside us. The pieces of space where those things can talk to one another.”

As Richter and the ensemble begin to let the music speak for itself, a tall line of lights behind the musicians glows and recedes. Throughout the evening, it changes subtly with the mood of the music: warm, cool, sometimes absent, sometimes blindingly bright. It fits the simplicity of the music being played and feels, as the music often does, simultaneously futuristic and mid-century.

The musicians and Richter move through In A Landscape, perfect renditions of the recordings, occasionally pausing to let field recordings or sequences of pre-recorded music play. For most bands and musicians, this slavish adherence to the written note and studio might feel sterile or unthinking. But, just as each musician uses paper manuscripts to play simple songs that they have likely played hundreds of times together before, this faith in the music is a choice that allows them to be wholly present in the moment, and their focus is very much on each other and the audience. This is key to the power of watching Max Richter and experiencing his music live. This connection and what he chooses to do with it.

Many songs begin with long, slow cello bows; gradually, a viola line is added, then subtle violins and the soft, warm sounds of Richter’s muted piano. The piece builds, swelling as individual parts shift subtly to accommodate other players. This description could fit many modern composers or pieces by other modern minimalists like Michael Nyman or Gavin Bryars, but what Richter focuses on, as he said, is the communication between the inside and the outside world.

Here, Richter isn’t only speaking metaphorically. His music entrains the audience, physiologically matching the state of the performer and the listener. Because of the slow tempo and the frequent use of two descending notes looped over a repetitive cello part, our heart rates are lowered to the tempo of the music. The man who pursued this particular power of music to send hundreds of people to sleep at his Sleep series of concerts tonight pulls the venue into a quiet world of contemplation and gentle awe at this simple skill. Once we reach the intermission, the lobby is full of chatter, a refreshingly diverse blend of people reflecting on the experience they shared.

The original album of The Blue Notebooks, released on an imprint of the UK indie label Fat Cat Records, featured the actress Tilda Swinton reading from Franz Kafka's The Blue Octavo Notebooks. In his introduction, Richter explains that, along with wanting to write a protest album about the Iraq war, the feeling underpinning the album is one of doubt, a sensation that Franz Kafka was, he tells us, “The patron saint”.

Tonight, as Swinton is otherwise engaged, we get the closest thing Australia has to her, Eryn Jean Norvill, the actress best known for playing all 26 characters in Sydney Theatre Company’s 2022 production of The Picture Of Dorian Gray. Norvill gently and forcefully intones brief diary-like passages from The Blue Octavo Notebooks between Richter’s equally gentle and forceful music.

While much of it sounds like it could have been composed at any time in the last century, it is hard to imagine it not possessing the same power centuries ago and in any number of culturally diverse environments. Conversely, the electronic interludes that occasionally break up the classical music use sounds that are very specifically early 2000s, reminding the listener of the political influence of the album that feels like they could equally apply to the disengagement of most people that allowed the invasion of Iraq to take place, and – particularly in the tumultuous closing piece The Trees – the toll of looking directly at it. A powerful and memorable concert from a generous composer who thinks deeply.