In the early hours of June 1, 2008, a fire tore through Universal Studio in Hollywood. This must have looked dramatic enough, flames leaping up the same Empire State that King Kong climbed, destroying the cabin terrorised by the Creature of the Black Lagoon. But one of the less recognisable buildings affected was an anonymous warehouse called Building 6197.

Building 6197 was being rented by Universal Music Group, the world’s largest record company. The label that boasts Drake, Taylor Swift and Arianna Grande and owns the recorded canon of Frank Sinatra, Queen and The Beatles. It was where they were storing their vast, largely uncatalogued trove of master tapes. The destruction was incredible, reels reduced to ash, tape canisters reduced to charred chrome sludge.

Initial reports barely mentioned the loss of tapes. A burned factory isn’t as remarkable as a burned film set. And, after all, the music had ‘already been digitised’ so would still be around for ‘many years to come’.

The roll call of the tapes lost is pretty incredible, REM to Tupac, Elton John to No Doubt. But there were also masters from legendary subsidiary labels like Decca, Chess and Impulse. The losses from Chess records, for example, include masters by Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Etta James and Aretha Franklin. The original recording of Rocket 88 and Rock Around the Clock. Records that it would be no exaggeration to say created youth culture, the bedrock of pop music.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

There were also tens of thousands of never before heard field recordings of bluegrass, classical, gospel, spoken word and blues. Documents of history and culture. Aural time capsules of a world lost to living memory.

"Watching the flames literally melt the sound of Aretha Franklin’s voice, you can’t help but feel that something beautiful has been lost irrevocably."

Why are master tapes important? Let’s back up. Music is vibrations in the air, it’s supposed to be heard in the moment, anything else – no matter how high its fidelity – is a compromise. The wonders of technology can improve on that compromise, but nevertheless, what you are hearing is invariably a copy of a copy of a copy. The master tapes are as close as you can get to the source of the sound. The drums, the vocal, the strings are separate, not condensed. Warm, varied and human, not flat and condensed.

To rehash a tired analogy, the masters are the equivalent of the Mona Lisa. Not Mona Lisa the image or the concept, the Mona Lisa, the one that came into being through Da Vinci’s very hand. A CD is the equivalent to a glossy print available in the gift shop, a streamed MP3 is the equivalent of looking at a GIF on your phone or laptop.

But there’s more to it than that. When you listen to a Joni Mitchell master tape you are listening to the sound of her finger on the fretboard, her breath on the microphone. It’s the spectre of that moment in 1971 when – thanks to an impossible confluence of cultural and historical chance – a young woman walked into a recording studio and played and sang. Any future version is water in the wine.

And now the pure wine, the source, is gone in one fell swoop. The New York Times called it the “biggest disaster in the history of the music business”, but it’s hard to know how to feel about it, there’s no one to blame, no direct victim.

True enough, an alternative narrative to this story is that this is no great loss. Isn’t this just a story that affects audiophiles? Most people (myself very much included) can’t tell the difference between Spotifying R.E.M through headphones bought from an airport newsagent and listening to R.E.M on 180-gram vinyl through the kind of soundsystem that Bryan Ferry might appreciate. Who cares if the masters are gone? One less overpriced reissue for MOJO magazine to indiscriminately give five stars to. But to such a narrative I would say; very short-sighted thinking. It’s a bit like saying the Rosetta Stone isn’t important because you now have an app on your phone that can teach you Greek.

"And I’m not Jack White, I don’t care where things are recorded or how. I care about how those recordings make me feel."

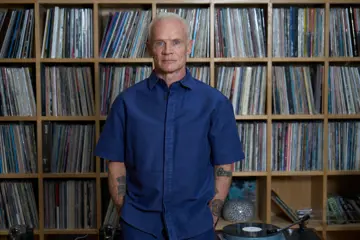

Years ago, with British India, we had been working for a few months at a beautiful old studio in Melbourne. Our tenure there had come to its bittersweet end and the studio owners were done trying to make ends meet. Rents were rising at the same rate as the popularity of bedroom recordings. The Fleetwood Mac/Roxy Music model of deluxe studio recording had never seemed more obsolete. The control room had a confounding but beautiful 24-channel sound craft mixing desk, the last thing to be moved from the studio. The studio owner (a warm-hearted Dutch guy who had been super kind to us) told us it wasn’t worth the hassle of moving, and though there are a handful of gear-geeks around the world who would cherish it, the cost of getting it too them would make the sale redundant. He then stood by stoically as two of my bandmates took to it with sledgehammers.

It seemed such an extreme solution. Completely of the moment. Maybe the demand for things like this is low now, but how will a piece of gear like this be viewed in fifty or one hundred years?

And I’m not Jack White, I don’t care where things are recorded or how. I care about how those recordings make me feel. But watching those sledgehammers fall, or watching the flames literally melt the sound of Aretha Franklin’s voice, you can’t help but feel that something beautiful has been lost irrevocably. Even when there’s no one to blame, even when the current state of culture makes it hard to articulate what it is, there has been a great loss.

And a loss that no one cares about somehow seems even sadder.