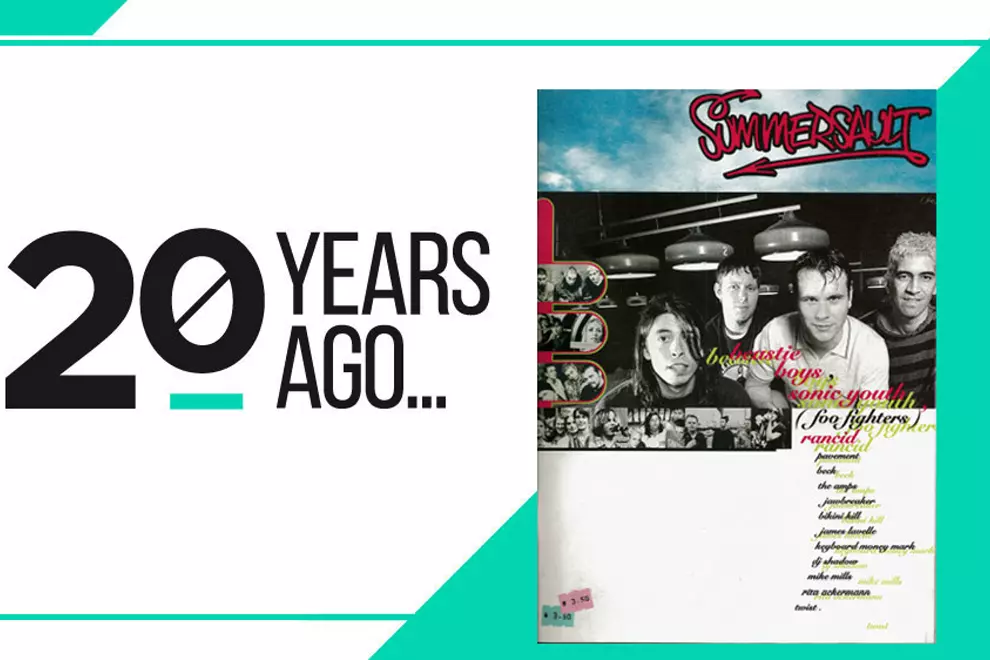

SUMMERSAULT FESTIVAL

Melbourne: 29 Dec 1995, Royal Melbourne Showgrounds

Sydney: 31 Dec 1995, Macquarie University

Gold Coast: 2 Jan 1996, Douglas Jennings Park

Adelaide: 5 Jan 1996, Adelaide Entertainment Centre

Perth: 7 Jan 1996, Fremantle Oval

Two decades ago, then-fledgling promoter Stephen “Pav” Pavlovic put on a travelling festival whose line-up included Beastie Boys, Sonic Youth, Beck, Foo Fighters, Pavement, Rancid, Jawbreaker, Bikini Kill and The Amps and lost so much money he nearly killed his music career before it properly began. How?

From purely a punters’ perspective — as with the equally doomed Alternative Nation, which was held in April of 1995, never to be seen again — Summersault Festival was a resounding success, a full day of brilliant international and Australian music staggered over two stages for maximum immersion, with barely a break for respite. Most of the bigger bands involved were at, or close to, the apex of their careers (with the notable exception of the Foo Fighters, who were just making Dave Grohl’s first tentative forays after the sad demise of Nirvana the previous year) and everyone put in top-notch performances: the only thing really missing was decent crowds, otherwise the venture could have been viewed as nothing but a massive success. But the people didn’t come, and Summersault too eventually disappeared into the ether, never to be staged again.

So what happened? The foreword of the Summersault magazine/program (available in newsagents in the weeks leading into the festival for $3.50, and including programs and interviews with all of the international acts) seems to hint at both expected longevity and some quest for redemption (albeit printed in the form of mock front-and-back book flaps), adapting the summary of what seems to be Terry Goodkind’s 1994 debut novel Wizard’s First Rule (or perhaps its 1995 follow-up Stone Of Tears) via cut-and-paste so that it reads:

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“Juice Magazine called Stephen Pavlovic’s Summersault ‘a wonderfully creative, seamless and stirring epic fantasy debut’. Piers Anthony lauded it as ‘a phenomenal fantasy, endlessly inventive, that surely marks the commencement of one of the major Festivals in the World. It starts in early and keeps hitting you with new magical wonders, building into a truly gripping adventure.

In Summersault festival Stephen’s Pavlovic’s world was turned upside down. Once a simple promoter Stephen Pavlovic was forced to become the Seeker of Truth, to save the world from the vile dominion of Lord Sleaze, the most viciously savage and powerful wizard the world had ever seen. He was joined on this epic quest by his beloved Golden Girls, the only survivor amongst the Confessors, who brought a powerful but benevolent justice to the land before Sleaze’s evil scourge. Aided by Iku the last of the wizards who opposed Sleaze, they were able to cast him into underworld, saving the world from the living hell of life under Sleaze…”

It continues in this vein for a few more paragraphs, followed by a demented-looking photo of Pav (in turn followed by a fake author’s blurb; “STEPHEN PAVLOVIC burst upon the music scene with his masterful, best-selling festival SUMMERSAULT. He resigns (sic) in Sydney, Australia, where he likes to sleep a lot and steal other people’s ideas.”) and then one final tract:

“I must create a System or be enslaved by another [hu]man’s”

This being is a slightly mangled take on William Blake’s quote:

“I must create a system or be enslaved by another man’s; I will not reason and compare: my business is to create.”

(Click to enlarge)

It’s all fairly confusing until you begin to understand Pav’s relationship to the Big Day Out, with whom he was entering into cutthroat competition with his new festival venture under the sole auspices of bringing them down. One can only assume that ‘Lord Sleaze’ refers to one of the BDO’s co-founders, Vivian Lees (or maybe an amalgamation of Lees and his business partner Ken West), whilst the Blake quote relates to his opinion that he’d been unfairly treated by the BDO in previous years whilst helping them book big international acts through his touring company Golden Sounds.

Despite Pav’s tender years – he was still in his 20s at this stage – he’d already enjoyed a golden run as a promoter, his biggest coup arriving early in the piece when he signed Nirvana to tour Australia in early 1992, inking the deal just before they reconfigured the entire music world with the release of 1991’s smash-hit album Nevermind. In a 2012 interview with Mitchell Oakley Smith (‘Pav, The Music Man’, Manuscript Issue 3) he recalled:

“I was predominantly a fan and I just wanted to put on shows that I wanted to go and see. It was really DIY, and it seemed like there was this secret community of people doing similar things, so you really just felt like you were a part of something, and once you started connecting with a few particular artists, they dialled you into this global network of people doing shows, touring, promoting. I was working with Mudhoney, and the guys were friends with Nirvana and told me that I should tour them. It was just word-of-mouth that it came about, and all very lo-fi because I called up Kurt [Cobain] and asked if he wanted to come to Australia to tour.

"It was all new, and I was probably pretty naïve about the whole thing in just phoning people up, but back then bands didn’t have management like they do today. It was very underground.”

“Ever since bringing Nirvana to the bill of the first BDO, Pavlovic had bolstered the festival’s line-up with international headliners." — Luke Benedictus

As well as their own headlining shows all around the country, Pavlovic booked Nirvana onto the very first Big Day Out in 1992 (which was then a Sydney-only event at Hordern Pavilion headlined by Violent Femmes), thus starting a relationship which would exist as the Lees/West festival expanded into Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide in 1993 and then became truly national by adding Gold Coast and Auckland in 1994. The BDO was getting bigger and bigger but Pav felt that he wasn’t getting any fiscal recognition for his role in this growth. Luke Benedictus espoused in his article ‘The Beat Goes On’ (The Australian, 5 Sep 2008), “Ever since bringing Nirvana to the bill of the first BDO, Pavlovic had bolstered the festival’s line-up with international headliners such as Hole and Smashing Pumpkins. But despite attracting these crowd-pulling names, he didn’t feel he was getting the financial recognition he deserved.”

Craig Mathieson sheds further light on Pav’s mindset at the time in his tome The Sell-In (Allen & Unwin, 2000);

“The dynamic between Ken West and Steve Pavlovic was fraught, to say the least. They swung between friendship hinged on mentorship to jealousy and annoyance. By 1995 Pavlovic had become the indie entrepreneur, with his touring company, renamed Golden Sounds, as well as Fellaheen Records and the Australian franchise for X-Large, the underground fashion label co-founded by Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon [NB: it was actually Mike D of Beastie Boys who started X-Large and who franchised to Pavlovic; Gordon became involved later with offshoot X-Girl]. But it was the biggest venture he was involved in, the Big Day Out, that was upsetting him. After four years he felt that West and Vivian Lees at Creative Entertainment weren’t treating his groups with the same respect and courtesy as those they toured. Pavlovic was convinced that West and Lees weren’t paying his groups as much and that the benefits his bands brought in weren’t flowing on to him personally. ‘At the time I would to try and say to those guys, “I’m putting these bands on, they’re doing really well. I think you should take care of me”. A lot of those bands were creating the Big Day Out and I wasn’t getting any juice from it financially or credibility-wise.’

“Lees and West didn’t agree. They felt that Pavlovic’s acts wanted to do the internationally prestigious Big Day Out, and the fact that this cost him money wasn’t their fault. And the pay-off was that the structure let Pavlovic develop a band’s profile through the Big Day Out and meant they could run a profitable tour later on. ‘But all he ever saw that he was making fuck-all money in the first part of it,’ West says.

“The impasse simmered through the first half of 1995 before Pavlovic put an emphatic end to it: ‘Fuck you guys, these bands are the ones that are pulling the people to your shows. I’ll do my own thing,’ he told West. Pavlovic announced Summersault, scheduled to hit Australia’s main cities four weeks before the Big Day Out on either side of New Year’s Eve. He received an early boost when Triple J, who West had fallen out with the previous year, agreed to present the festival, guaranteeing a slew of on-air promotional cartridges.”

So, with that, the gauntlet was thrown down and it was, as they say, on. In a 1996 interview with Dave Grohl conducted during Summersault (‘Heartbreak High Wet Dream’, Blah Blah Blah) Michael Dwyer offered of Pav’s experience putting the line-up together:

“Even in its inaugural year, Summersault is the festival the stars ask for by name. The brainchild of 18-year-old (sic) Sydney impresario Stephen Pavlovic, it began life as a routine Beastie Boys Australian tour. Until their mutual friends caught wind of it and started making long-distance calls, Sonic Youth threw their hats into the ring early, followed by their '95 'Palooza pals, Pavement.

"Pavlovic's company, concert promoters Golden Sounds, had worked with Nirvana in '92; still, he was pleasantly surprised when Dave Grohl called to offer the Foo Fighters' services. Kim Deal was next on the phone and, well, Beck felt like a holiday too. Bikini Kill and Rancid were invited later.”

Pav accused the BDO team of white-anting his relationship with his Perth site and causing him to lose that venue, while a bidding war for bands also pushed prices up considerably.

It’s hard to tell if it really did come together that easily when Pav decided to take on the Big Day Out, but he certainly put together a top-notch bill. Yet the line-up aside, things didn’t progress as smoothly as Pavlovic might have hoped, and things were turning ugly when it came to relations with his former BDO associates. According to Benedictus in ‘The Beat Goes On’, “The competition between the two festivals turned ugly. ‘People’s egos were involved,’ Pavlovic says. As the two went head-to-head over ticket sales, allegations of dirty tricks were rife and relationships deteriorated to the point that West threw a drink over Pavlovic in a Sydney bar.”

As far as the alleged ‘dirty tricks’ are concerned, Pav accused the BDO team of white-anting his relationship with his Perth site and causing him to lose that venue, while a bidding war for bands also pushed prices up considerably. According to Mathieson in The Sell-In, “there was fierce competition for silverchair’s Epic labelmates, the incendiary socialist metalheads Rage Against The Machine, which Creative won. The competition for skank-punks Rancid got so involved that the band eventually agreed to do both tours in a bid to keep each side happy.” [Writer’s note: for young punters smitten with the then recently released Rancid opus …And Out Come The Wolves, the fact that they played both clearly competing festivals in quick concurrence was at the time perplexing and awe-inspiring in roughly equal doses].

From Pav’s corner, there was a quiet confidence emanating, no doubt stemming from his golden run over the past five years when he’d displayed something of a Midas rock’n’roll touch. He told Benedictus in ‘The Beat Goes On’, “I was in the right place at the right time. I was bringing out bands like Smashing Pumpkins and Green Day, who started having huge mainstream hits while the world of the Jimmy Barnses and the Midnight Oils was going down the other side of the hill. It was just this real changing of the guard and Nirvana put a sledgehammer through the door and broke it wide open."

By any measure, if you’re looking at it from a creative/musical angle, Summersault Festival was nothing if not an unmitigated success.

It seems that, despite all of this angst and vengeful competition seeming intuitively counterproductive, Pav was somewhat blinkered and thinking only in the now, ignoring the bigger picture altogether. In more to-and-fro with West — this time in a Juice Magazine article titled ‘Our Man Pav’ (Dec ’95) — the author Simon Woolridge opined: “West based the Big Day Out on the relaxed atmosphere of matey connections (just has Pavlovic has done) with the Violent Femmes and others. And he says Pavlovic will soon learn that “unfortunately the mates system doesn’t last too long”. ‘I’m not thinking about next year,’ Pavlovic counters. ‘[Summersault] is basically a show that I want to see…’”

And by any measure, if you’re looking at it from a creative/musical angle, Summersault Festival was nothing if not an unmitigated success. This scribe attended the Gold Coast event and even 20 years later the day/evening brings back a river of positive memories. Finally seeing NYC emo-punks Jawbreaker just after their farewell one-two punch of 24 Hour Revenge Therapy (1994) and Dear You (1995) was revelatory (they split up later in 1996). Witnessing the Pixies’ Kim Deal playing with various Guided By Voices as The Amps (her first-ever Australian performance) was fantastic. Indie legends Pavement were at this stage touring behind their third album Wowee Zowee and on this day catapulted from one of my favourite bands to my favourite music act of all time (despite having seen their previous tours something just clicked this day).

Bikini Kill were a ball of barely concealed rage and vitriol, one which seemed slightly out of place in the afternoon Gold Coast sun but which prompted much investigation of this great band after the fact. 1995 being the year after Kurt Cobain’s sad demise the Foo Fighters’ eponymous debut album was like the first bloom of new life after a bushfire, and seeing these songs in the flesh was like a new step in the healing process for the death of the grunge era (they were brilliant that day, even though I can’t abide the stadium behemoth they eventually mutated into).

As mentioned, ska-punks Rancid had just dropped their seminal …And Out Come The Wolves album and seeing those raucous, uplifting numbers in the flesh for the first time was incredible. This Summersault dalliance with Sonic Youth was my first of many, and although I wasn’t overly familiar with their oeuvre at this stage I remember being blown away by their passion and conviction. Beck played in solo mode – favouring his folky One Foot In The Grave material rather than the better-known Mellow Gold stuff, both records having dropped in 1994 – but it was a welcome respite from the unrelenting rock we’d experienced so far, and then the Beastie Boys brought it all home (it had only been a year or so since I’d seen them headline Livid so this wasn’t so thrilling, but still a strong memory). Plus there was a slew of great local talent on each line-up, making for truly strong and rounded bills.

But where were the punters? There are numerous reasons that, it seems, conspired to bring down this awesome music line-up, some controllable and others not so. From a perspective of the Gold Coast leg (with which I’m most familiar) the show was on a Monday at Douglas Jennings Park on the Gold Coast spit — it’s not easy to get to (even if you’re on the Gold Coast), plus the weekday meant that a lot of the target market were immediately out of the picture due to work (most of my friends couldn’t attend for that reason).

To top things off, Summersault was not only competing against the Big Day Out but in Queensland was up against the then-thriving Livid Festival (whose brilliant 1995 instalment featuring Rollins Band, You Am I, Alex Chilton, NoMeansNo, Morphine, Powderfinger, Custard, Babes In Toyland, Jello Biafra and countless others had only happened on 25 November, some five weeks beforehand) and also the fledgling Homebake Festival in Byron Bay, whose debut gig was the actual day after Summersault and whose advertised bill featured You Am I (eventually late withdrawals), Magic Dirt, Spiderbait, Powderfinger, Silverchair, Regurgitator, Tumbleweed, The Mark Of Cain, Screamfeeder and Grinspoon (this opening gambit also proving a brilliant day despite the inclement conditions turning the venue into a mud bath). When combined, this all represents a lot of competition for punters in a festival market which was at this juncture far from established, and one that was probably also wary of unscrupulous interlopers following the ignominious demise of Alternative Nation earlier that year.

It seems that the Big Day Out brand was strong after their initial victories and people decided to stay with what they knew.

A contemporaneous MTV review of the final Perth leg of Summersault stated, “Despite the stinking hot temperature (37 degrees Celsius) somewhere between 10,000 and 12,000 music fans rolled out for the last Summersault, bringing total punters around Australia to around the 50,000 mark (about 18,000 attended the biggest show in Sydney on NYE).” This overall figure represented only a third of the tickets sold by the Big Day Out for the 1996 instalment, despite that festival having an arguably lesser line-up (it eventually proved a stellar day itself, featuring Rage Against The Machine, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Rancid, Billy Bragg, Porno For Pyros, Powderfinger, Radio Birdman, Elastica, The Prodigy, Reef, TISM, Dirty Three, Regurgitator and many more big names). It seems that the Big Day Out brand was strong after their initial victories and people decided to stay with what they knew.

There were also reports of profligate spending in and around the touring Summersault shindig. Anecdotal reports of people arriving to venues in boats and even helicopters abounded, and Kathleen Hanna (the frontwoman of Bikini Kill) recently recalled to The Music Network’s Nathan Jolly (‘Girls To The Front’, Jan 2014) when questioned about the start of her love affair with the Beastie Boys’ Adam Horowitz, “It was on the Summersault tour that Steve Pav did, and it only happened once, so it wasn’t like the Big Day Out; I think he lost his pants, his underwear and his shoes on that deal. We’d never been on a big festival tour at all, we had nice hotels; we were, like, living large – we were so excited because we’d always stayed on people’s floors. We’d never had that kind of treatment, and Steve made sure that all of the bands – whether you’d played by the port-a-pottie or by the dumpsters, or on the mainstage – got treated the same. We all had nice hotels, that’s why he lost so much money.”

Despite these huge losses, it wasn’t immediately evident that Summersault was a fiscal failure; plus, it should be noted that Big Day Out took a pretty massive hit too itself from all of the bidding wars and competition for acts and ended up taking a year off in 1998. When asked whether the Big Day Out could have ever disappeared for good, Ken West told The Music Network’s Lars Brandle (‘Big Day Out: The Mechanics Of Awesome’, Jan 2011), “Sure, plenty of times. No worries. 1996 was a gamble, which is why BDO 1998 didn’t happen: we were up against Summersault.”

"[I] felt really disconnected from the artists and the music side of everything, which is why I started doing this in the first place. It was as though I was working in admin." — Stephen Pavlovic

In his Billboard piece ‘Finding The Audience’ (Sep, 1996) Christie Eliezer posited, “Big Day Out 1997 is the last (for some time, at least) as the promoters say they are tired of mounting the event. Those behind rival festivals Golden Sound’s Summersault and Frontier Touring’s Alternative Nation insist that those will endure and fill the vacuum.”

History tells that neither Summersault or Alternative Nation endured beyond their first year, while the Big Day bounced back to enjoy another 15 years of prosperity before it, too, succumbed to various factors and bit the dust after the 2014 farewell. From Pav’s point of view, it seems that the dragging of the counter-culture into the mainstream, which had so buoyed his career in the first place, ultimately aided in the downfall of his career as a tour promoter, telling Oakley Smith in ‘Pav, The Music Man’, “There was no definitive movement, but the kind of music I was interested in suddenly became part of popular culture, and that brought with it more structure and organisation, and some of the contact we had with artists in the early days now has a wall of people in the middle. That’s a necessity and something that we deal with, and it actually makes a lot of the procedures run a lot smoother, but at times I do feel a bit removed from it as a result… I lost a whole bunch of money on a festival [Summersault] and, at that point, felt really disconnected from the artists and the music side of everything, which is why I started doing this in the first place. It was as though I was working in admin, just stamping papers and organising stuff”.

Pav further confirmed this to Benedictus in ‘The Beat Goes On’: “The reason we ended up in that situation probably was within our control,” he reflects. “And it probably came from being naïve and not planning properly, and from having had a dream six years where everything just worked.” Pav told XLR8R’s Andrew Parks (‘Labels We Love: Modular’, Sep, ’09) that this voluntary administration process was like “an outside business going over all the accounts, assets and creditors to find out the best solution for everyone concerned”, with Parks then observing, “In Pav’s case, the conclusion was clear: he was done with concert promotion and already onto the next phase of his career, Modular Recordings.”

Summersault deserves to be remembered for its strengths rather than its weaknesses.

According to Mathieson in The Sell-In, we almost lost Pav from music altogether: “After Summersault he’d been unsure about his future, swinging between building a new touring company or, as a practicing Buddhist, moving to a Thai monastery. Music won out and he started from scratch, just he and one associate working from his lounge room”. Over the next decade-and-a-bit, Pav would build Modular into an international behemoth, becoming intrinsically involved in the careers of bands such as The Avalanches, Eskimo Joe, Ben Lee, Wolfmother, Tame Impala and many more fine bands, no doubt utilising skillsets and gleaned from the disastrous Summersault debacle all those years ago (although that venture too has hit its share of road bumps in recent times).

Yet overall, despite how it panned out, Summersault deserves to be remembered for its strengths rather than its weaknesses. If only all mistakes and life lessons came with such a brilliant soundtrack as Summersault did back in the summer of ‘95/’96. It might have failed financially, but as a music fan it was one incredible day of diverse and passionate rock’n’roll. Happy 20th anniversary, Summersault.

Further viewing

Foo Fighters’ full Summersault Sydney performance (31/12/95)

Audio of Nic Dalton & The Gloomchaser’s song Okay Sydney, You Beat Me (which at the 2:35 mark features the line from the Half A Cow founder and former Lemonhead, “Made up the name for the Summersault Festival, but then Stephen wouldn’t put my name on the door”).