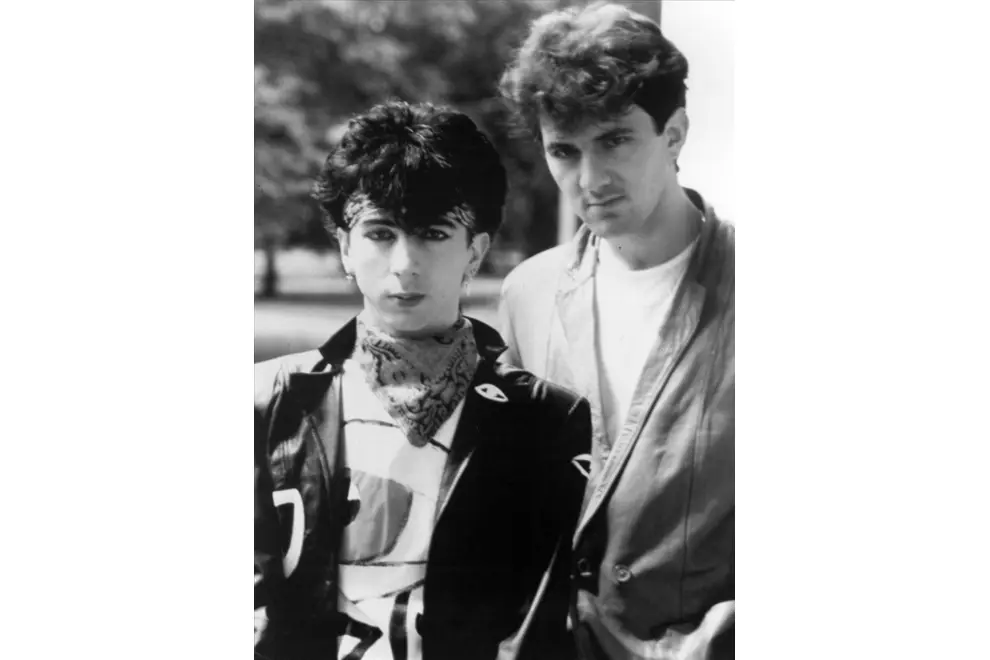

Soft Cell

Soft CellBeing a songwriter is hard. And I’m not just talking about the fact that writing great songs is no easy task. I’m talking about how the economics around songwriting have made turning it into a career a near impossibility. Songwriters don’t get paid upfront for their work. They only get paid via the royalties their songs generate after they come out. In other words, if your song doesn’t sell, you don’t get paid.

While this labor arrangement makes things harder for songwriters, it’s nothing new. It’s how songwriters have been paid for a long time. That said, something has died in the streaming age that has made it even harder to survive as a songwriter. That something is mechanical socialism. And I don’t think it’s being discussed enough.

Soft Cell’s luck was laced with a tinge of un-luck. After their first few singles flopped, the group had one more chance before their label would kick them to the curb. They decided to cover an obscure song from 1964 that had recently found a second life in the United Kingdom’s club scene: Tainted Love.

Whereas the original — as done by Gloria Jones — was frantic, the drummer pulling along the Motown-ish guitar and horns as if they were running late for lunch, Soft Cell’s rendition was a touch more relaxed, the arrangement reimagined for the 1980s with drum machines and synths. Musical decisions aside, Soft Cell’s updated version of Tainted Love saved their career. It sold over a million copies in the United Kingdom and cracked the top ten in 15 different countries.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

So, what was bittersweet about this world-conquering song? Soft Cell put out a version of The Supremes’ classic Where Did Our Love Go? on the B-side. In 2023, David Ball, one half of the British duo, described the choice of the B-side as “the most costly idea of our career.” How could pairing a Motown-ish cover with a Motown cover be so costly? To understand that, we need to understand a bit about how songwriters get paid.

As I noted at the beginning of this piece, songwriters are generally not paid upfront for their work. They are paid when their songs generate royalties, which is a fee paid to a copyright holder for the use of their intellectual property. While there are a handful of royalties that can generate income for songwriters, the two most common are performance royalties and mechanical royalties.

Performance Royalty: Since 1897, songwriters have been owed royalties each time one of their songs is performed publicly.

Mechanical Royalty: Since 1909, songwriters have been owed royalties each time one of their songs is reproduced physically or digitally.

While I am presenting these concepts very broadly, the specific things that constitute a song being “performed publicly” or “reproduced physically or digitally” have been strictly defined over the decades via legislation and judicial precedence. Here, for example, is how the US performance rights organization ASCAP (the US version of APRA) defines a public performance:

A public performance is one that occurs either in a public place or any place where people gather (other than a small circle of a family or its social acquaintances). A public performance is also one that is transmitted to the public; for example, radio or television broadcasts, music-on-hold, cable television, and by the internet … Permission is not required for music played or sung as part of a worship service unless that service is transmitted beyond where it takes place (for example, a radio or television broadcast). Performances as part of face to face teaching activity at a non-profit educational institutions are also exempt.

So, if you go to a bar and the DJ is spinning the latest hits, that’s a public performance. If you do karaoke on a Friday night with some friends, that’s a public performance. If a character in Seinfeld recites a snippet of Petula Clark’s 1964 hit song “Downtown”, that’s a public performance. If you listen to some muzak while on hold with your doctor, that’s also a public performance.

Mechanical reproductions of songs are just as varied. CDs, cassettes, and vinyl all considered reproductions. Downloads from digital music stores like Bandcamp are too. Even a music box that is operated by a tiny hand crank falls under this umbrella.

Admittedly, this is all kind of confusing. And there isn’t some internal logic that governs how it all works. It’s based on a century of arguments and compromises. Nevertheless, we have enough knowledge to understand why Soft Cell described putting out a cover as the B-side of Tainted Love as “the most costly idea of [their] career.”

Had they put an original song on the B-side, they would have been paid a mechanical royalty each time the Tainted Love single was purchased. Because they didn’t, only Ed Cobb — the songwriter of the A-side (i.e., Tainted Love) — and Lamont Dozier, Brian Holland and Eddie Holland — the songwriters of the B-side (i.e., Where Did Our Love Go?), got paid a mechanical when the single was purchased.

Imagine for a moment that Soft Cell did write the B-side. It’s likely nobody would have bought the Tainted Love single for that hypothetical original song. People wanted the A-side. In terms of mechanical royalties that wouldn’t have mattered, though. That royalty would be generated even if you never played the B-side. This is mechanical socialism. It benefited songwriters greatly in the age of physical media but has died with the proliferation of streaming. Let’s head back to the 1990s to understand why.

In 1994, vocal group Boyz II Men released their third studio album confusingly named II. Driven by the success of the singles I’ll Make Love to You and On Bended Knee, II became a smash hit, selling 12 million copies before the end of 1996. When your record sells 12 million copies, you make a lot of people a lot of money. In Boyz II Men’s case, one of those people was Tony Rich.

Tony Rich is a Grammy-winning singer-songwriter that made his name as an in-house songwriter for LaFace Records in the 1990s. He had one cut on II, a downtempo number called I Sit Away. I Sit Away was not a well-known song on II. It was never released as a single and was unlikely to be the reason that anyone bought the album. Again, that didn’t matter. Each of the 12 million times that II was purchased, Rich collected a mechanical royalty of about $0.066. That’s not much per copy, but all of those pennies add up to around $800,000.

Things would be very different in the streaming era, though. After two decades of negotiations, it was determined that interactive streaming services (e.g., Spotify, Apple Music, Audiomack, etc.) pay both mechanical royalties and performance royalties each time a song is played but non-interactive services (e.g., Pandora) just have to pay performance royalties. Thus, if you open up Spotify and listen to I Sit Away, a mechanical royalty will be generated for Tony Rich. He gets no direct benefit if you stream one of II’s big hits, like I’ll Make Love to You and On Bended Knee.

If you look at the play counts across the album, you’ll see how this makes I Sit Away much less valuable these days. It only accounts for 0.21% of the album’s nearly 550 million streams. The math is a bit more complicated here, but I’m almost certain that Tony Rich would not be getting a near-million dollar mechanical royalty payout had II come out last year.

I find it difficult to say if this change in how songwriters get paid is better or worse. For one, songwriters who wrote hits always made much more money than those who only got one cut on a popular album. Along with generating royalties from album sales, hit songwriters would also be making money from having their songs sold on their own, performed more often, and played in the background of television shows and movies. Furthermore, our socialistic past was driven by the fact that data-tracking was less precise. In fact, I’d bet old school mechanical royalties would have been paid out differently if the music industry had been able to track usage rather than purchases. Now, we have access to that information.

Still, part of me feels like we lost something. As I mentioned at the beginning of this piece, being a songwriter is hard and finding success takes at least a little bit of luck. The winner-take-all nature of mechanical royalty payouts in the streaming age has benefited the lucky few at the expense of a shrinking middle class of writers. While I am not ready to advocate for the return of mechanical socialism or a new method to pay out mechanical royalties, it’s worth thinking about how we can improve the lives of songwriters in the 21st century.

Chris Dalla Riva is a musician who spends his days working at Audiomack, a popular music streaming service. He writes a weekly newsletter about popular music and data called Can't Get Much Higher. His writing and research has also been featured by The Economist, NPR, and Business Insider. Can’t Get Much Higher is also available as a podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Substack.