Attendance at small-to-medium-sized Australian music venues has fallen on average by 60 percent. Patrons are drinking 70 percent less, rent prices are up 34.7 percent, and insurance premiums vaulted by up to 500 percent.

12 venues closed in Adelaide over the past 12 months, many after their leases came up for renewal. Up to 400 could go throughout Victoria. While many run month-to-month, in early February the Federal Government introduced an alcohol tax, the third-highest in the world. It has meant two payments a year for operators, and added an extra 90 cents on a pint of beer.

Tam Boakes, who owns Adelaide’s Jive club on the Hindley Street entertainment strip, summed up what every other operator was thinking. “My reaction was, ‘Can we take any more of this?’ When there’s nothing left and you’re at the absolute bottom, you think, ‘Where do we go from here?’”

The tax is passed on to drinkers, which will further hit the volume of drinking by patrons. “You can’t put anything more on the punters because the punters are not spending,” Boakes explains. “You can’t charge more for tickets because you want people to come to the shows. There are absolutely no profits in smaller venues at the moment.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Ben May, who runs Sydney’s Mrs Sippy and the Gold Coast’s Burleigh Pavilion, feels sorry for his patrons. “It’s getting harder and harder for people to go out and enjoy themselves.”

Jasmin Patel, owner of Mr Goodbar, is predicting more closures in Adelaide’s West End this year.

Overshadowed

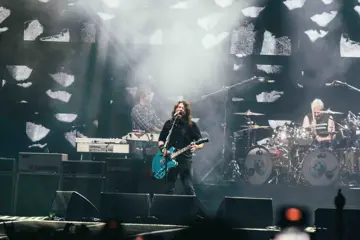

The ticket frenzy for international tours and the breaking of attendance records at festivals and stadiums/arenas has completely overshadowed that the post-COVID demand for live music has not extended to smaller venues. The exceptions are clubs for certain sub-genres.

They couldn’t trade for two years due to restrictions but still had to pay rent and utility bills. The impact of cost-of-living concerns has been devastating for these venues.

It’s a national crisis for these spaces, of course. But Adelaide seems to be the flashpoint for all that’s gone wrong. That’s partly because it’s a UNESCO City of Music, and because 12 venues brought shutters down in the past 12 months. Half of those went dark over the recent holiday period.

“It’s an absolute battle,” Boakes confirms. “I’ve been (in the West End) for 20 years and I’ve never seen a time like it. We predicted this would happen post-COVID and it’s happened. We lost audiences, we’ve lost a lot of skills and a lot of artists. It’s going to take years to rebuild those things. Then you add cost of living to it. Unfortunately when there’s a financial crisis, entertainment is the first to go. So many venues were edging on bankruptcy as it was [because of COVID] and this comes right after when there’s not much. It’s terrifying how many venues are closing.”

Support Act reports a 40 percent growth in callers to its Helpline in the six months between July and December 2023, compared to the same period in 2022. “We don't have any details about how many callers are from the live sector or music venues,” CEO Clive Miller reveals, “[but] the main presenting issue is anxiety followed by personal issues and career concerns.”

He adds: “Sadly, we have all read about the number of venues that have been forced to close over recent months. On the upside, we now have Federal and State Governments who are committed to reviving the nighttime economy and working with venues to try and resolve some of the very complex issues they face.”

Insurance Nightmare

Insurance remains a nightmare. Taking Melbourne as an example, Cherry Bar and Yah Yah’s had a 500 percent leap, while many were forking out $160,000. A report in The Age found that some insurance clauses border on the comical: the Old Bar in Fitzroy not only saw premiums escalate from $10,000 a year to $60,000, but has a ban “on people dancing with a drink in their hand in the venue’s small bandroom”.

The Australian Live Music Business Council, which negotiated deals for its members through companies Nexus and Ausure, predicted on A Current Affair that Victoria could lose up to 400 spaces. In the 2022 Victorian Live Music Census, released last April, there were altogether 1,076 of these throughout the state.

Grassroots venues have a much deeper problem that has to be addressed. It goes back before COVID, to the advent of streaming, explains Dr. Sam Whiting, lecturer in Creative Industries at the University of South Australia and author of last year’s book Small Venues: Precarity, Vibrancy And Live Music.

Once music fans got their exposure to new bands from triple j, community radio and the music press. They searched them out in grassroots spaces and followed them as they built up their careers. But with streaming’s switch to algorithms and curated playlists, “a lot of young people are not getting exposed to local artists as often. So the connection between audiences and local artists has been disrupted somewhat.”

Solution #1: Council-Run Venues

The idea of music venues being run by music fans, local councils or a State Government – something which works well in the northern hemisphere – is something that’s increasingly discussed in Australia as inner-city property value escalates and bills seem insurmountable. The conversation needs to move from a venue’s profitability to “intangible assets, such as music and the arts, that need to be supported,” according to Alison Avron, director of The Great Club in Marrickville, Sydney.

Dr. Whiting asserts: “Things are going to get worse for smaller venues in the next few years because we’re facing market failure of them as commercial enterprises. Running a small venue as a commercial business is becoming increasingly difficult. An overly financed property market impacts rent and other overheads, and turns environments, particularly urban environments, into an assets market economy. Venues can’t compete with this. If they don’t own the freeholds to the building they operate, which is the case with most music venues, they have to pay rent all the time.”

Strictly on economic terms, the pressure is lifted if a community of music fans (with a variety of skills including financial and marketing acumen), a local council, or a State Government, run a venue as a nonprofit venture. Overheads are paid without trauma. The venue becomes a community hall, where locals hang-out, learn skills and join a wellbeing hub. Recording studios and rehearsal spaces are set up inside, with the idea they will be self-sufficient. Any profits go to extra payment for musicians, production workers and staff.

“Local governments or State Governments should be running music venues,” stresses Dr. Whiting. “They should start to purchase these spaces when they’re at risk. They then bring them into the same sort of facilities as libraries and community halls which we take for granted as part of our civic infrastructures.”

In the UK, the Music Venue Trust (MVT) has raised £2.3 million ($4.46 million AUD) from the public to buy the freeholds of nine grassroots venues. A community-run spot is Sister Midnight in South London, operated under Lenny Watson who had run a record store and venue previously. When the chance came to save Sister Midnight, he marshalled the forces.

“I didn't have really high expectations for how this was going to develop and how much support we'd get,” he said. “But now we have around 950 members and I’m training to become a cooperative practitioner myself.” It’s building up a donation pool of £500,000 ($970,884).

The idea has been tried in Australia. When The Tote in Melbourne seemed to be in danger from developers, the idea was raised to buy it for $6.65 million and place the freehold into a charitable trust. The owners of the Last Chance Rock & Roll Bar came up with a bit over half. In six months last year, 3,000 members of the public came up with $3 million (via Pozible) to set up a foundation which would own the building. Among the 3,000 contributors were owners of fellow venues Whole Lotta Love, the Gasometer, FeeFee’s Bar and the Gold Coast’s Vinnie’s Dive Bar.

Music fans and industry executives have risen in the past to keep venues going. Three years ago Adelaide’s music community exceeded the $70,000 crowdfunding target to keep Jive alive. Three years ago, when Crowbar Sydney launched a $100,000 campaign after being hit with 30 percent trade decline, artists donated records and test pressings, while Lindsay McDougall offered his first Frenzal Rhomb guitar.

Whether this idea of bureaucrats taking over their venues goes down with some owners remains to be seen.

Boakes agrees with any move to ensure a venue’s longevity, but has reservations. “I’d love to see that happen with a couple of venues. It acknowledges them as culturally significant places. They’re important for communities, and they are very safe spaces,” he says. “If someone wants to purchase the Jive building and have me run it with passion and ensure its legacy, and not competitive to other businesses, and guaranteed they won’t be knocked down for apartments – sure.”

Solution #2: Council-Insured Venues

This week, independent councillor Stephen Jolly was set to move the motion that Melbourne’s Yarra City Council consider for the March meeting that it “assist local venues [by] taking out insurance on their behalf.”

Rather than be left to insurers, venues in its 12 localities – including music hubs like Collingwood, Richmond, Carlton North and Fitzroy – would be covered by the council’s insurer. Jolly told The Age: “Yarra is the hub of live music in Melbourne. If these venues go down the gurgler because they’ve been squeezed by insurance companies, then not only is that a massive cultural blow for inner-city culture and the nighttime economy, but it’s an economic hit too. We can’t just wash our hands.”

Solution #3: Ticket Levy

In the UK, ticketing platform Ticketmaster ran a monthlong donation scheme last October, where its customers could donate to the Music Venue Trust. Ticketmaster would match the figure. Elsewhere, platforms such as Skiddle and Good Show agreed to donate a percentage of sales.

The Independent Live Music Alliance in South Australia, made up of seven outlets, is talking to larger arts festivals about the Big Ticket Levy, a donation of $1 from each ticket sold. Their premise is that festivals get millions of dollars in funding from the State Government. “It’s also an acknowledgement of the importance of the work grassroots venues do to find the talent that they feature,” a spokesperson said. “The response has been positive but the concern is how it would be implemented.”

Solution #4: Greater Government Interaction

Getting closer to the workings of levels of Government is something the live sector is working on.

Among the recommendations by Matt Levinson’s Gig Economy: Making Sydney A Great City For Live Music report late last year – commissioned by urban policy think tank Committee for Sydney – was an expanded Hospitality Concierge for venues, a live music liaison in police commands, and the notion that live venues be included in precinct and region planning.

This month, Adelaide lawyer and live music activist Antonio Tropeano circulated a letter to both sides of South Australia’s Parliament warning that unless the 3am to 7am lockout was lifted, the West End would become a “ghost town after dark”.

Independent MLC Frank Pangallo is in the process of setting up a Parliamentary Committee to review the lockout laws.