Blak Label Music

Blak Label MusicLittle known to the industry are those behind the scenes, none moreso than Blak Label Music, the independent First Nations-owned and -operated record label who are in the midst of an ongoing mission to not only nurture Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) artists, but to bring their stories and voices to a global audience.

The origins of Blak Label Music came about largely in part because its founders, Mitaru “Mit” McGaughey and Issac Barton, saw there was a market, a need, for better and greater representation not only for ATSI artists within the Australian music industry, but the way they are treated, revered, and educated in a business context. Having initially met through CareerTrackers, an Indigenous internship programme that helps Indigenous youth enter work incorporate Australia, McGaughey and Barton, later along with third co-founder Carlos Prince, decided to start making music together. From there, they said to themselves, “It would be awesome if we could help mob make music.”

“We started a music production company to help mob make the music and art they wanted to make,” says McGaughey, a proud Kulkalgal man from Warraber and Poruma Islands in the Torres Strait. “As we dove into that, we recognised there’s this huge gap, especially for emerging musicians, not just in First Nations artists but once they have the music, they don’t know what to do with it. How to market it, distribute it, they don’t know what that means.

“We found there was a glaringly big gap in the industry for First Nations people [to] work with First Nations people on the business side of the industry. Therefore, being able to work with the music and understand the narrative. We changed our business model to reflect a record label because it’s something the wider industry can easily understand, but we’ve developed it in a way that reflects the community and the values of First Nations people.

“It largely is a community-driven record label with elements of education on both sides; not only educating the artists, but the industry.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

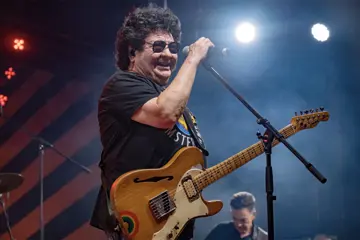

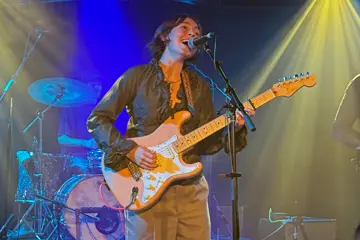

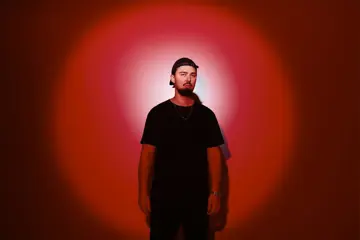

After a few iterations of Blak Label Music, mid-2020 saw the official launch of what the company is today. And on their books today, Blak Label Music boast the likes of Denzel Kennedy, Charli Oh, Alf The Great, Yung Whitty, T33, doyouloveme, and Quinta. They’ve also recently curated their first event, at SXSW Sydney last month, thus beginning to bolster a tighter focus and brighter spotlight on emerging ATSI artists.

Operations Director Eden Sher builds on McGaughey’s remarks, saying, “As a non-founding member and the only non-Indigenous person at Blak Label, what I saw is the passion and drive to teach First Nations people to be self-serving around understanding ‘Here’s not only how to make music, but here’s how to release music and how to do it sustainably. There’s a massive focus on sustainability rather than quick hits; that’s how I see the industry now. The desire for Blak Label [is] to not be in its own lane, in the sense that you look at record labels only want to do promotion for a particular product, booking agents are only focused on getting one artist to where they can make money. Blak Label is a label only in the sense that that’s what the industry understands and that’s our bread and butter.

“We’ve recently been thinking about ourselves as an interface between the structured industry and this segmented approach, and then applying what we’ve learnt of the industry to First Nations creatives and putting on that First Nations lens and gathering as much knowledge as we can and spreading it out.”

Because of that lens, Blak Label Music now has a great network of First Nations creatives, comprising of people in music, visual, video and much more. The label’s team are able to draw on a wealth of skills and knowledge in such a way that when an opportunity comes to them, they can say a band deserves to be raised up. They do so not because it’s the done thing, for the First Nations ascription, but because these First Nations artists have talent. The very existence of such a label as this has a domino effect in more ways than one. We’re looking at the continuation of history, a chance to see what continuing songlines looks like in this century. It’s a thought both McGaughey and Sher think of as interesting. “On one hand the artists we work with definitely see the weight of the work that we’re doing,” begins McGaughey, “they really love to contribute to our vision as well, not just through the music but advocacy as well.

“Eden and I talk, and sometimes we ourselves can’t fully grasp the breadth of what we’re working towards. We’ve been doing this without really understanding the effect this may have on the industry, just because it’s something we see as a thing that should be done.”

The ball of powerful effect is already rolling, as Blak Label Music have drafted an exclusive digital distribution agreement with Xelon Entertainment, who are invested in supporting the First Nations music Blak Label want to deliver to the world. “A lot of the contracts in the music industry fail to contemplate the differences in working with First Nations artists,” says McGaughy. “Our approach was to work with a distributor who would be open to coming on the journey with us in figuring out what we need to think about when distributing for First Nations artists, and a lot of that came back to cultural awareness and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property [ICIP].”

With a legal background, Sher is aware that the Western method of doing business is dependent on contracts and touch points, governed by a rigid document. “For us to continue our mission, to exist in spaces and change them slowly through advocacy and action, one of the touch points between a label and an artist is a licensing agreement; that music flows from the label to distributor, so we have to make sure we’re taking that music and treating it correctly at each of the touch points. The best way to show the industry how that’s done is through a licensing agreement. It also espouses our role as Blak Label.”

That agreement has seen Blak Label Music engage Simpsons Solicitors to draft what is likely the country’s first culturally aware and safe Licensing Agreement. Sher says, “As we talked to a bunch of law firms and vetted them, making sure they’d be culturally aware, culturally safe, and treating our artists and their music and what we’re talking about with as much passion and as much sensitivity as we were. Simpsons were a fantastic partner in that.

“We now want to understand from the start to the finish how to protect and proliferate our artists.”

This distribution agreement, for Blak Label Music and First Nations artists, means two things; confidence for the label in working with artists, and having flexibility to make quick changes because the company’s distributors are legally aware that changes may arise. “It [also] now enables us to confidently distribute music,” says McGaughey, “so we can work with emerging artists that have stories or are making music and put that on Spotify, make it easily accessible for people outside of their community. Those are the two ways that are beneficial to us and our artists, but also other emerging First Nations artists.”

Sher adds, “The real attention behind this, is we’re breaking ground. To be able to show and legitimise and validate the, not just work and effort behind it, but commercial viability is important for the industry as a whole, we now take this agreement and show other labels, this is how we protect First Nations artists as a record label.

“Behind all of this is the massive piece we’re still doing, and that’s around cultural protocol in general – ways of working, ways of dealing with and handling and distributing in protecting practises in a practical way. That’s the real confluence of knowledge, to go, ‘Here is, practically speaking, ,a protocol document. As an industry partner and a person dealing with recorded music, if you want to work with First Nations people, this is the gold standard.’ It contemplates differences in mobs and cultural practises. That’s the stuff that is so lacking in the industry.”