William Crighton

William CrightonWilliam Crighton knew it was time to come home.

He had spent a good part of his 20s in the United States, touring, getting some breaks, meeting the right people and some of the wrong people too. After being based in Nashville for a few years, things were looking up for his music. But something was bugging him.

“When I went to America I thought music was about something else,” Crighton says. “When I got there I realised that a good portion of it was about the haircuts and the make-up and what you have to sell. I remember going to a writing session in Nashville where there were farming magazines on the table and they were skimming through them looking for inspiration. I thought, fuck this.’’

Crighton and his young family moved to a rural setting at Burrinjuck on the Murrumbidgee in New South Wales.

“We missed Australia, the people, the land, and frankly I wanted to tell my own story. I came home with a longing for connection and though music was a part of me I still didn’t know how I would be able to do it.”

Which is when songs started to pour out, songs that couldn’t come from anywhere else. They were as evocative of his homeland as anything by The Triffids or Midnight Oil.

2000 Clicks begins: “2000 clicks from the Queensland border, lying in a ditch out west of Wagga”, the kind of line which hooks the listener and ensures they stay to find how it all turns out. And Riverina Kid is a tragic story that’s as dark and harrowing as it is starkly beautiful.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

So had he found his voice? Crighton answers with the same kind of succinct language you hear in his songs: “Once you start writing from your heart properly, the songs start to give you your voice.”

The rest of the story is better known, since songs like these helped make Crighton’s self-titled album one of the most impressive debuts of 2016. Then 2018’s Empire, cranking up the electric guitars to match the emotional intensity, blew away just about everyone who heard it.

These are followed by Water And Dust, out on Friday, with searing songs like the title tune with its refrain: “We are the children/Water and dust/We belong to mother/She don’t belong to us.” In Your Country, Jeff Lang’s slide guitar combines with the didgeridoo of William Barton to startling effect as Crighton rages: “I don’t understand why they’re still clearing the land/Why they’re poisoning the water.”

Stand, written with Midnight Oil’s Rob Hirst and with Hirst on drums, is a long way from the writers’ rooms of commercial country. The accent, the songs, the stories and the attitude on Water And Dust are as Australian as can be.

Things are certainly going well, with an album that is going to be hailed as an Australian classic, although when we catch up the Crighton family is in isolation recovering from COVID at their home in the Hunter Valley. Good timing, it turns out, with Crighton back on deck for the release of the album and to play two sold-out shows with Midnight Oil on their farewell Australian tour.

As he tells the story of his life, from small towns in the Riverina and tentative Tamworth talent shows to Beijing, Los Angeles and Nashville and back again, you see how every backroad and obstacle along the way helped make the songwriter who can create a statement that feels as vivid, as true, as Water And Dust.

“Church hymns was where it started,” Crighton says. “We were a Christian family and my nan would take me to church where we would sing all those old hymns. And my mum singing me folk songs like Where Have All The Flowers Gone?

“When was I was five or six, every arvo after school I would go up to sing to my grandfather who was in bed dying of cancer. That showed me the power of music, how singing could affect people. I started writing songs pretty much from that early age.”

There was time and space to explore the natural world, out in the bush, fishing the river. His parents divorced but Crighton heard the songs of Johnny Cash, Hank Snow and Willie Nelson out in the truck with his father. Three-minute lessons in how to tell a story.

By the time he was in high school William, younger brother Luke and their mum were settled in Tumut in the foothills of the Snowy Mountains. Someone in a record shop turned him on to Lucinda Williams’ Car Wheels On A Gravel Road, and from there it was a short trip back to Neil Young and Joni Mitchell.

You take the step into that world, with a passion and hunger to find out more, and people take a step toward you. Like Tumut bluesman Col Ray Price, who would drive Crighton in his Cadillac out to the Sunday blues nights in a taxidermy shop in Adelong, opening Will’s ears to Big Bill Broonzy, Howlin’ Wolf and more. Will’s mother took him to the Tamworth country music festival which is where he first met Julieanne when they appeared in the same talent quest. Back in Tumut, Will started to play shows with Luke on bass. Then a series of unlikely turns took him to America.

Sam McNally, from ’70s Australian band Stylus, asked him to sing in a group he was putting together for a three-month season at a flash venue in Beijing. Many times they played to an empty room and it was hard to see where this was leading. Then one night Edward Norton, Naomi Watts and people from the crew making the film The Painted Veil came in. One of them was James Sarzotti, who became a friend and occasional co-writer and encouraged Crighton to move to the US, by this time with Julieanne and their first child Olive.

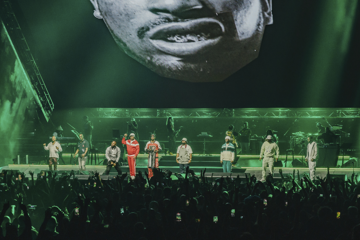

Pic by Renae Saxby

Pic by Renae Saxby

In Los Angeles Crighton connected with people like Don Peake of fabled studio session band The Wrecking Crew, who played with everyone from The Everly Brothers to Marvin Gaye, and violinist Scarlet Rivera - that’s her on Bob Dylan’s Desire - would come down to join the raw young Aussie on stage.

“At this point I didn’t know what I was doing or where I was going,” Crighton says. “I just felt I was on a path to learn something.”

In Nashville Crighton met drummer and producer Matt Sherrod, known for his work with Crowded House and Beck, and who has played a crucial role on all three of Crighton’s albums.

“Matt helped me break out of the path I was on and get me on the one to finding my own story. We were working with a producer who was pushing us a certain way and Matt said, ‘Music is more than about this.’ It was good to hear that from an older brother.”

Which brings us back to Australia and Water And Dust, an album made by a writer still burning with the need to learn from the past, to experience the country, to make music with a deeper understanding of Australian history and First Nations people.

Killara is one of Crighton’s most haunted songs, beginning with an arrest on the streets of Glasgow and a convict’s passage to Sydney Cove, part history and part dream. While there is darkness in Crighton’s music there is plenty of light and hope too in songs like Keep Facing The Sunshine, written and recorded in a day at engineer Christian Pyle’s studio in the Byron Bay hinterland.

The album concludes with Crighton’s musical setting for Henry Lawson’s poem After All, which begins: “The brooding ghosts of Australian night have gone from the bush and the town/My spirit revives in the morning breeze.” Which sounds just like something Crighton could have written.

Daughters Olive and Abigail contribute backing vocals on the title tune while baby Jack will have to wait for his chance. And with William each step of the way is Julieanne, who contributes as vocalist, co-writer and much more.

“She’s instrumental to the whole thing; we’re a team. There’s a mutual understanding where you bypass the bullshit you might have with someone else. Then you can get down to the heart of what you are doing. That’s how I see it.”

It took some time, but now a lot of other people are seeing it too.

Water And Dust is released on Friday through ABC Music. For all upcoming tour dates, click here.