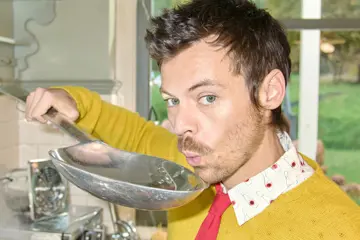

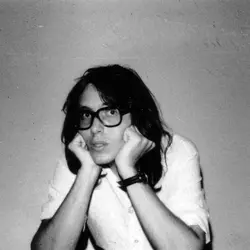

Van Duren

Van DurenWhat happens when you discover a musician whose music blows your mind but has been seemingly forgotten by the world? That was the conundrum facing Sydney musician Wade Jackson and his band manager mate Greg Carey when they stumbled upon the 1977 solo album Are You Serious? by a shadowy figure named Van Duren.

While Van Duren’s music was undeniably world class – pure, passionate power-pop with a clear lineage to the work of Lennon and McCartney through the filter of subsequent acts like The Kinks and The Hollies – the artist himself seemed to have been forgotten by time, lost in the margins of our often unforgiving popular culture.

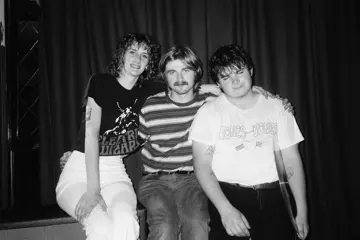

The tale of how Jackson and Carey eventually tracked the singer down and became intrinsically implicated in his life story, creating new film Waiting: The Van Duren Story, contains as many twists, turns and random happenstances as does the at times incredible narrative they uncovered surrounding their subject and his beautiful music.

Having been introduced to Are You Serious? by a random Sliding Doors social media moment, the pair of friends finally tracked Van Duren down in his hometown of Memphis, where he was still plugging away on the local scene, and were quickly beguiled by a fantastical tale jam-packed with famous stars, amazing musicians, music industry chicanery and even Scientology, all soundtracked by the amazing music they’d already fallen in love with.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

“When we first set out to do it, in our minds – from the little we’d heard at that stage – it was just a 20-minute YouTube documentary showcasing Van’s music,” Jackson recalls. “Then we finally got him on the phone, and after the phone call, which was about two hours long, Greg called his wife and said, ‘We’ve got to do this!’ and we bought our plane tickets to the States immediately, because it was, like, ‘Holy dogfight, this thing’s opened right up, this is insane.’

"Holy dogfight, this thing’s opened right up, this is insane."

“That’s when we found out about the Big Star connection – Big Star’s been one of my favourite bands for years – and the Memphis connection and Andrew Loog Oldham and everything else.

“I’m sure there’s probably thousands of stories like this on fantastic musicians who never made it, but I don’t know if they all have this type of intense, amazing narrative leading to the present day.”

Van Duren, for his part, had initially been dragged into the orbit of cult Memphis power-pop icons Big Star having known drummer Jody Stephens at high school. He failed an audition to join the band during its latter stages, but upon its dissolution in the mid-‘70s, was soon writing and recording with Stephens and guitarist Chris Bell in their outfit Baker Street Regulars.

“There’s a lot of levels to that,” Duren reflects. “I’d known Jody for about five or six years by the time we actually got to play together, which was in ’75, shortly followed by the band we had with Chris. I was a really big fan of Chris from Big Star’s first album #1 Record [1972] but I didn’t really know him until about ’74, and I was really intrigued by him.

“He was the antithesis in some ways of who I was. I came from a blue-collar family, working class, and he was obviously from a wealthy family, from different sides of the tracks. So that alone intrigued me, but his talent – his guitar-playing and his songwriting – just blew me away, so being able to play with him, even though it only lasted six months or so, was quite an education for me.

“I was the bass player at the time – I doubled on piano a little bit – but I was mainly the rhythm section with Jody, and I’d be watching what Chris was doing on guitar and it was really hard for me to keep my focus because he was just so amazing.”

Despite being short-lived, his time spent in the Baker Street Regulars also proved influential in honing Duren’s blossoming songwriting skills.

“I’d been writing songs from the very first band I was in, which was when I was 12, because being a fan of The Beatles that’s where it all came from initially for me – I just assumed you started a band and wrote all your own songs – and boy, they were really terrible for about eight or ten years,” the singer laughs. “About the time I started working with those guys, the songs were getting better, and by the time the three of us actually played together, Jody and I had already done some demos at [legendary Memphis studio] Ardent Studios, some of mine and some that he and I wrote together.

“I think I was coming up with some pretty great songs and they were part of our repertoire along with the Big Star stuff and Chris’s solo stuff.”

When that star-studded outfit led nowhere, Duren soon followed his solo dreams to Connecticut, where Are You Serious? was conceived and recorded, teaming up with small independent label Big Sound.

“At the time it was my only opportunity – or I considered it to be my only opportunity; at that stage I considered [it] to be my last shot even though I was only 23 or something like that,” he continues. “I’d just been up against so many walls in Memphis because what we were doing musically seemed perfectly normal to me but apparently what we were doing was against the grain of what was going on, in terms of being able to work here in Memphis.

“I thought it was my last shot and it was bittersweet to leave Memphis behind – to drop everything and buy a one way ticket – but I did it, and I don’t regret a single moment of it. I had the opportunity and I was really great to have that opportunity.”

Nonetheless, he was about to discover that, as well as making dreams come true, the music industry can be spectacularly cruel and exacting. Having released Are You Serious? to strong reviews and gaining some sizeable traction around the country, when time came to make the follow-up he was confronted by some increasingly strange hurdles.

"It was high pressure on me for over a year to quote-unquote 'join' Scientology, and I knew it was a load of crap – I knew it."

“It was like something from a bad movie,” he sighs. “We’d done the first record and everything was great – everybody at the studio was great and I felt that for the first time I had some professional people behind me – even though they were on a shoestring budget as both a record company and a studio.

“Then we put out the first album and during the tour, the studio and label came back to me and said, ‘Ok, let’s do a second album,’ because they were selling records: it wasn’t going gangbusters, but they had airplay on over 100 FM stations around the country, so the future looked bright.

“So later in ’78 I got into the studio and started working on the second record and just weeks into that, all of a sudden Scientology overtook the studio and almost every single person working there. So it was high pressure on me for over a year to quote-unquote 'join' Scientology, and I knew it was a load of crap – I knew it.

"So anyway I just kept my head down and finished that record – my only goal was to somehow finish that record – and as soon as I had the whole thing mixed and got it on a cassette, I just walked, I had to.”

“Then of course [second album Idiot Optimism] stayed in the can for about 20 years, which was heartbreaking. I knew that second album was far better than the first one – it was just a different animal. When you do your first record, everything that you’ve written that’s worth a damn up to that point, that’s what you do on that record. Then you wait one year and you’ve got to come up with that much material again, and it was, like, ‘Oh oh, let’s just see how creative I really am.’ And I just stepped up – I really had it in me – and I’m not one to blow my own horn that much, but in this case that was a great record.”

Understandably, according to Duren, it was a terrible feeling having his art suppressed like that; making something that he was really proud of but not being able to share it with the world.

“It destroyed me, it really did,” he ponders dolefully. “I took it hard in a big way, and within a couple of years I came back to Memphis licking my wounds, I didn’t know what else to do and I was starving. I came back to start over, and of course because I’d been gone four years, everything in Memphis had changed and nobody knew who I was.

“I ended up starting another band the next year in ’82 called Good Question; we were instantly popular and that band lasted for 17 years. We did some records but we were a great live band too, and that was basically the first time I was ever making a living making music – a living above the poverty line.

“The thing is that even though I was heartbroken about Idiot Optimism not coming out, you gotta look forward and say, ‘When can I do the next record?’ and so on, and that’s what’s lead to this soundtrack album [for Waiting] being album number 13. My career’s been continuous – and I’m really proud of that – and it startled Wade and Greg when they found out that I was still active! I’ve been active all this time, putting out records, obscure as they were.”

Having used their sleuthing skills to track the singer down in Memphis, Jackson admits that he and Carey had no real idea what they were doing from a filmmaking perspective, making the strength of their finished documentary even more impressive.

“It was funny because once Jonathan [Sequeira, producer] cut that first trailer it was a very emotional time, and Greg and I went and had a few beers and just went, ‘Holy shit!’” he laughs. “I remember telling him that I’d been thinking the whole time, ‘I hope Greg knows what he’s doing because I feel like I’m following him,’ and then he said that he’d been thinking the same thing about me!

“The fact that we were so naïve – and I don’t mean any disrespect to filmmakers – but that’s what got us through. We didn’t really understand about post-production and how long all this takes, and I’m really impatient so if someone had told me it was going to be three years before it came out from the initial concept, I probably would have walked away.”

Fortunately they stuck to the task and ended up with something that the subject himself holds in high regard, surely the main consideration at the end of the day.

“It’s their film – I want to make that clear if it isn’t already, I had very little to do with the actual film other than providing the material they’d asked for and being interviewed,” the singer states. “I put them in touch with 40-odd people, I guess, who were involved in those records back in the day and other people who were contemporaries and Andrew [Loog Oldham] and so on, but beyond that it was their vision – and Jonathan the producer’s vision – and I’m really amazed what they did, I was really floored when I saw it for the first time.

"I’m really amazed what they did, I was really floored when I saw it for the first time."

“You know how it is, when you haven’t seen it you’re going, ‘Man, what am I going to do if this sucks? I can’t just walk away!’ I wasn’t really thinking like that – although I did joke about it a lot – but by the time it finished, I knew those guys pretty well, but I had no inkling they were going to put out that strong a finished product and I’m really proud of it and happy about it.

“But that said I’ve always been the person who looks to move forward in every way that I possibly could. Especially creatively, if you’re writing and recording the last thing you want to do is repeat yourself over and over so move it forward and let the past be what the past is. So to suddenly turn around and focus on something from 40 years ago is kind of a trip, but there’s nothing there I’m embarrassed about.”