The Pogues

The PoguesLegendary London outfit The Pogues are a band at once defined by the decade in which they rose to prominence – their classic body of Celtic-flavoured punk was crafted in the '80s, and a product of that decade's political and societal upheaval – but also one out of sync with that same era, for their unique music and persona was completely and utterly different to everything surrounding them at the time.

The band were informed by the spirit of punk that had energised the London scene so brightly in the late-'70s before burning out or mutating into other musical forms, but they married this manic energy to the ramshackle bonhomie of traditional Irish folk songs to make something completely distinctive and timeless, a music certainly rooted in geography but not mired to a particular epoch.

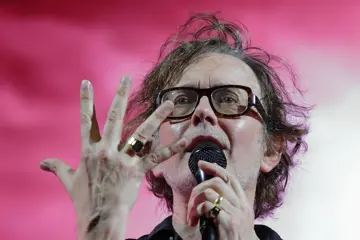

It's fitting that the band's creative core – shambolic frontman and songwriter Shane MacGowan (already an identity in the London punk community before the band got off the ground) and tin whistle player Peter “Spider” Stacy – famously first met in the toilets at a Ramones gig in London, little knowing the long-term ramifications that this chance encounter would have on the rest of their lives.

“And The Saints!” Stacy exclaims of that fateful evening. “The Saints were the first band on that night – an Australian connection! I love that band. It was The Saints and Talking Heads and the Ramones. It was great – Talking Heads in between The Saints and the Ramones! I felt sorry for them before I saw them, but once they started I knew they didn't have anything to worry about – they were fucking great. And The Saints were fucking great, then the Ramones were stunning.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

It was a couple of years after witnessing that amazing proto-punk line-up before The Pogues played their first show – they played one infamous gig as The New Republicans, before changing their name to Pogue Mahone (Gaelic for “kiss my ass”) which eventually morphed into simply The Pogues – and in that intervening time their wedding of rock and folk came to stunning fruition.

“I honestly don't know how conscious it was,” Stacey recalls of the embryonic Pogues sound. “Essentially what happened was that Shane and I were around at a friend's house, and he picked up a guitar and started playing [Irish folk tune] Poor Paddy On The Railway, just playing it really fast – he was essentially doing an 'acoustic punk' version of it, for want of a better expression. Whether or not that was something he'd had running through his head anyway or just something he did there and then on the spur of the moment I really don't know, but we looked at each other and a sort of light bulb went off. It still took some time for that to coalesce and form and eventually form into The Pogues, that was 18 months before the first Pogues gig.

“If you took the amount of time that was spent actually getting [the aesthetic] together it probably didn't take that long at all. Shane and Jem [Finer – banjo] were knocking a few ideas around after the show we did as The New Republicans – the germ of the idea had remained, it never really went away. It was always going to turn up somewhere, because it worked so brilliantly – it was like a marriage made in heaven.”

When things took off for The Pogues it was with the force of a hurricane. Supports with The Clash lead to headline tours and their 1984 debut Red Roses For Me, and before long the band had made headway both in the UK and overseas. There was a definite political bent to their music – many songs concerned the trials and tribulations befalling the working class – but there was also a radical, hedonistic edge to both their many songs about drinking and their actual lifestyles that made everything they did so distinct. This reckless element that made the band so beloved as rogues to so many eventually proved their downfall, when just after the release of their fifth album Hell's Ditch in 1990 MacGowan succumbed to alcoholism and drug addiction and was forced out of the band. The Pogues continued for a few more years – first with punk icon Joe Strummer out front, then with Stacy handling vocal duties – before finally calling it quits altogether in 1996.

“There was a lot of very intense touring, which is probably one of the reasons why we burned out the way that we did, or more accurately the way that Shane did, although he was far from the only one,” Stacy reflects. “But he personally just found it too much – the amount of touring that we were doing was insane, and really not conducive to any longevity, or so it seemed at the time. I mean when Shane left the band went on for another few years, but when Shane left the real proper heart of The Pogues went with him. We sort of carried on, and it was The Pogues, but his songs are such a defining part of what the band is about that it's very difficult to take one away from the other. Well it's stupid even thinking about it, you couldn't have The Pogues if you took Shane's songs away, that goes without saying.”

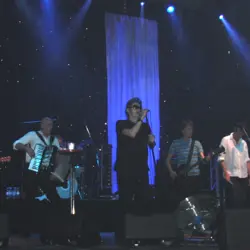

Eventually, in 2001 The Pogues – including MacGowan – reformed for a Christmas show, and since then have been playing sporadically, now branching out again into the overseas realms (their impending Australian trip will be their second, following their inaugural visit in 1989). Their music is still reaching new audiences – resonating as fully with new fans as it always has with the stalwarts – precisely due to its inherent timeless nature.

“I think that's got a lot to do with it, the whole idiom wasn't really tied to any particular decade, or if it was it was the 1780s or something like that rather than the 1980s,” Stacy laughs. “Plus also the quality of the songs – with Shane's songwriting plus a lot of the songs that we covered like The Band Played Waltzing Matilda and Dirty Old Town and those kind of songs – they are themselves kind of timeless songs, and played in that particular way they're not specific to any era. There were a lot of bands from the '80s who clearly sounded like they were from the '80s, but we were something apart. And I think underpinning it all – the really crucial thing – is the strength of Shane's songwriting. With all of those other things you could present a good body of work, but when you've got that added ingredient you're on to a winner. And I can say that without blowing my own trumpet – he's the one.”

While The Pogues are often mistakenly taken for an Irish band because of MacGowan's prominence and songwriting bent, most of them are Londoners – was it easy at the outset to embrace the music's Celtic flavour?

“Yeah, there's something really appealing about the whole thing,” Stacy muses. “Plus you've got to bear in mind that growing up in London – especially near where I grew up in London – there are some very Irish areas, so it wasn't something that I was unfamiliar with at all. But in a funny kind of way nothing prepares you for actually going to Ireland, because it's kind of in a way like Britain, but in another way absolutely nothing like it at all.”

For now there are no plans afoot for new Pogues music, they're completely content having fun with their current catalogue and taking this music to fans old and new around the globe.

“Yeah, it actually relieves us of so many pressures – not having to worry about the legacy, not having to worry about living up to what we've done in the past,” Stacy considers. “It just wouldn't work, a new Pogues album. You have to look at the songwriters and say that Shane as the main songwriter is not the same person that he was 27 years ago. He's not going to be writing the same sort of songs, so you'd get something that might be a Pogues album in name and it mind sound kind of like The Pogues but it wouldn't really be The Pogues. Unless you had that sort of continuity of creativity – like someone like Nick Cave as obvious example, or someone like Tom Waits , people who turn out consistently high quality, well-realised work, and they're always looking to improve on what they've done before – with that continuity it's a different story, but when you've had a break of 21 years since Hell's Ditch came out, it's just too long a time.

“Plus, it doesn't seem that we need new music to reach new audiences – a lot of the fans coming to the shows these days are very young, there's no way that they were even thought of when we were around before. I guess we've always been popular in colleges and universities and stuff like that, given the strong sort of alcohol content in our songs – I think that possibly explains that in part. Going back to the late-'90s before the first reunion tour I had the impression that we'd kind of been forgotten about almost, but you realise that just because you don't see your name in the papers that often it doesn't mean that people aren't listening to you and digesting and absorbing what you're doing. So you're getting bands coming out that have shown [that we've been an] influence, and there's obviously been this line of people that have been listening to us, it's just moved down the line.”

And finally, will Stacy be bringing any of the beer trays with him that he was so fond of whacking on his head as percussion back in the day?

“Oh yeah, but it will probably be pizza trays!” he guffaws. “I don't know what the story is in Australia, but it seems that in the rest of the world the beer tray is a thing of the past, or it's become a valuable antique. If I'd realised that they would become this resource I might have treated them with some respect! No, I wouldn't have actually...”