Recently, two big-budget Hollywood films featuring characters with a disability, The Upside and Welcome To Marwen, have been released in the United States, which finally kicked off a much-needed conversation about disability representation in the media. An outcry against the able-bodied actors (Bryan Cranston portraying a quadriplegic wheelchair user and Janelle Monae playing an amputee) hit the internet, and people began entertaining the idea that maybe, just maybe, there were disabled actors out there capable of inhabiting those respective roles.

UM, HELLO! Of course there were! Disabled actors exist, and they should have been hired for those roles. End of story.

This idea should not be controversial, yet many argued that Cranston and Monae were cast because they were the 'right actors for the job'. Cate Blanchett chimed in on the conversation about picking the 'right actors for the job' - in terms of queer visibility, but amidst ongoing conversations in Hollywood around race and disability as well - with her opinion that actors should be able to play roles outside of their lived experience. This argument bears weight, but only in select cases. For example, Ms Blanchett has played an elf, despite never being an actual elf herself (as far as we know – we are yet to hear an outcry from the elf population).

However, disability is different. Firstly, because disabled people are real, and secondly, because when able-bodied actors “crip up” they effectively steal roles from the disabled community. If Cate was right, and all actors could truly play roles outside of their lived experience, then disabled actors could depict able-bodied characters on screen. But that never happens ever, and not for lack of technology. Seriously, we’ve all seen Bradley Cooper play a talking CGI racoon in Guardians Of The Galaxy – surely Hollywood could use the same special effects magic to create legs for an actor who is a wheelchair user.

The problem is disabled-identifying actors are rarely given a chance to become established actors in the first place, particularly when able-bodied actors are taking up disabled roles. Furthermore, when we prevent disabled actors from being able to play disabled roles, which are, by anyone's admission, already few and far between, we deprive audiences of a realistic portrayal of life with disability.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

One particular example of this narrative springs to mind: the 2017 film The Shape Of Water. The movie focuses on a deaf woman who begins a sexual relationship with a subhuman fish creature because he is the only one who can 'understand' her on a deeper level. Read any review from well-respected pop culture giants like Variety, IndieWire or Rolling Stone, and you will find able-bodied critics praising the film’s powerful love story.

"Imagine what kind of reaction a Hollywood blockbuster would get if it cast a disabled actor in a leading role? The internet would probably break, and for once it wouldn’t be because of a Kardashian’s arse."

However, when The Shape Of Water hit cinemas, many unsatisfied disabled-identifying writers penned pieces from their own perspective, arguing that the movie perpetuated harmful narratives about 'othering' disabled people. In an interview with Huffington Post, writer Elsa Sjunneson-Henry stated that the movie sent the message that “disabled people should go and be with their kind”. She also pointed out that one of the rare times she was able to watch a disabled character have a legitimised romantic relationship on screen, it was with a monster. The Shape Of Water‘s negative stereotypes against disabled people were further reinforced by the film industry when it picked up four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The fact that Sally Hawkins (who portrayed the lead deaf character) was not deaf herself was just the cherry on the shitty representation sundae.

The concept of disabled people as outsiders or “other” is not The Shape Of Water’s invention – it is an attitude held by able-bodied people and most of society. It is this unconscious prejudice which desperately needs be challenged. When stories about people with disabilities are told without the presence of actual people with disabilities, we actively discourage disabled voices from contributing to, shaping, and leading conversations in mainstream media. It’s a cycle that is begging to be broken. Worldwide, roughly one in seven people identify as disabled, yet this statistic is barely reflected in the media industry. According to UK film industry body Creative Skillset, only 0.3% of the total film workforce are disabled.

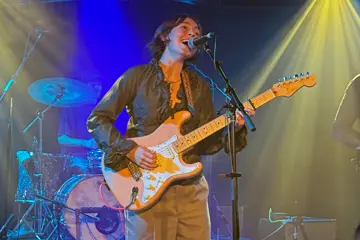

Though we still have a long way to go, positive change is becoming increasingly evident in the world of television. Speechless is a groundbreaking sitcom about an American family whose teenage son has cerebral palsy, and what’s more, they have cast a young actor with the same disability. The Last Leg is a British panel show hosted by Aussie disabled comedian Adam Hills, which began as a satirical look at the 2012 Paralympics and is currently in its 15th season. Even Australia is starting to get clued in. In 2018, live music program The Set was hosted by Paralympian Dylan Alcott, with a “house party” studio design that placed an importance on accessibility.

Another Australian show that was broadcast last year was ABC Comedy’s The Angus Project, which was created by us, the authors of this article, Angus Thompson and Nina Oyama. The Angus Project is based on Thompson’s real life and the plot revolves around a university student with cerebral palsy who parties really hard, assisted by his equally hedonistic care worker. By creating this show, we wanted to smash society’s perception that disabled people are outsiders who live in a sterile bubble.

The character of Angus is not defined by his disability, it’s just something he happens to have, just one drop in the ocean of character traits that drive him. After our pilot aired, we were inundated with messages from disabled-identifying folks and carers who were grateful for a television program which accurately represented their experiences on screen. If that unknown actor can garner this overwhelmingly positive response after being broadcast on ABC Comedy, imagine what kind of reaction a Hollywood blockbuster would get if it cast a disabled actor in a leading role? The internet would probably break, and for once it wouldn’t be because of a Kardashian’s arse.

Until Angus can go to America and steal a role off of Bryan Cranston, the disability representation problem isn’t going to solve itself. Casting disabled actors and including disabled voices in film projects is the first step to normalising disability, and changing the way able-bodied people think about what it means to have a disability.

This was originally published in the February edition of The Music magazine. Check it out here.