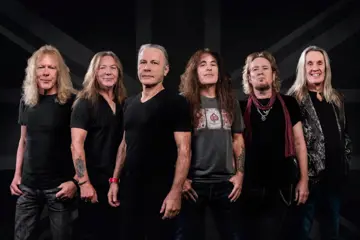

Pond

PondNick Allbrook, the 31-year-old frontman for Perth psych-rock band Pond – made up of Allbrook, Joe Ryan, Jay Watson, James Ireland and Jamie Terry – can come across as a kind of cult leader during their expansive live sets, seeming to almost proselytise to his followers as he jerks and kicks across the stage.

For his part, Allbrook sees that interpretation as a matter of perspective: “I'm sure other people would just think I was a bit of a little quince dancing around on stage... I reckon some people probably think I look like a wanker, and some people maybe think it's all real good.”

He appreciates the crowd’s response – expressing itself as a ritualistic, physical outpouring of emotion, bodies hurling against each other, arms outstretched: “I definitely wouldn't be making music and playing live if it wasn't for that.”

After the band took a break from touring and releasing music, Allbrook says he suffered from a crisis of confidence as a set of live dates loomed.

“I thought everyone was gonna see me and be like, 'Oh, he's different! Fuck this band, I'm out of here!' But it was like the opposite. We are fragile little wimps and we need constant reassurance that we're doing something ok, so crowds responding to us positively is essential to us making music.”

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

What got him through that experience were “beta-blockers” – drugs that inhibit the effects of adrenaline, often prescribed to beat anxiety – and the crowds themselves: “People's actual faces and bodies and voices right in front of me. I didn't need to block the beta for very long because seeing people physically react to your music is pretty powerful.”

While Allbrook is flattered by the image of himself as the enigmatic frontman, he doesn’t see himself as a “massive voice to the people”: “This idea of the artist as being a prophet isn’t true with me.”

But it’s still important to Allbrook that he uses his music to approach difficult subjects like climate change and national identity, as he does on their new record Tasmania, out this month, and on “sister album” 2017’s The Weather.

In the intervening two years Allbrook says the topics – especially around our obstinance in the face of man-made climate change – have “gotten more real and more scary”, and what his music offers is a “different, progressed take on them”: “It's harder to be like an angry, tub-thumping left-wing type guy and you start just feeling sad. Sad and desperate.”

What is a musician and writer’s role in tackling issues like these? “I think it's essential if you're actually concerned about it because otherwise you're not speaking your mind. And really, it's pretty important and I think whatever makes it louder, whatever makes people's dissatisfaction and fear and confusion louder and more visible is probably a good thing in the end.”

As an evolution from The Weather, Tasmania sees the band getting older and more honest lyrically, as they continue to explore the sonic textures of 808s and sequencers. They’ve reunited on the record with producer Kevin Parker (Tame Impala), who has worked with them on almost all of their albums except 2009 debut, Psychedelic Mango, first as their drummer and then producing since 2012’s Beards, Wives, Denim.

“We were getting more into [electronic music] gradually as the albums went on, sort of following this path down that kinda sonic territory and we just kept following it. I think we got a bit better at being honest lyrically and it's also a progression just as far as your outlook and what's consuming your brain.

"I didn't need to block the beta for very long because seeing people physically react to your music is pretty powerful.”

“It's just moved on, I like to think you're always learning and always progressing your views and stuff like that. I think it's a little bit more diverse in it being a bit more solemn and scared and resigned but also then stanky and joyful.”

That urge to be completely honest is, for Allbrook, “the only way to be truly satisfied with art or music you’re making”: “I just wanted to make something that was gonna make me feel good instead of feeling like there's still something clogged up inside of me.”

Allbrook says his “love for [the] country grows” the more he’s away from Australia, with the band keeping up a hectic international touring schedule: “It just blows my mind that people from far away appreciate what we’re doing.”

Explicitly local imagery comes through in the lyrics on Tasmania, which speak of frangipanis and bronzed chests and bushfires – even just on opener and single Daisy. Allbrook links that Australianness to getting older, and to a sense of nostalgia: “I don't know what it is but there's something about ageing that you just want to and you naturally turn into an old person and you start saying 'ripper' instead of 'sick' or something like that, you know what I mean?

“And nostalgia [is] being heightened by the prescient figure that it could all fall down soon. Or burn up soon or something like that. Or that the thing that I love so much is based on genocide and stuff like that – it just sorta preoccupies my mind.

“I find it really hard to write lyrics when I'm not quite emotionally piqued by something, and those sort of things are very emotional. They bring up a lot of fear and shame and pride and nostalgia, all of these vast dichotomies of feeling. So that's probably why there's a lot of songs about it because it's like all of these things are the things that make me feel enough to write something that I think is good.”

Allbrook became gossip fodder in September last year, when the Daily Mail cottoned on to the fact he had been dating Tiger Hutchence-Geldof since mid-2017. First, they used photos from Instagram to write about Allbrook and Hutchence-Geldof’s relationship, before going on to publish intimate pictures of the couple together in Birmingham, England.

He says he only found out about the articles because his manager sent them through to him: “It was pretty creepy because I had no idea that someone's taking a photo of me.”

And while he knows it’s just a reality of our age, where everyone has a smartphone with a camera, he still thinks it’s “fucked up”: “Having a zoom-in across the street on an intimate moment is real weird, yeah – it's quite creepy.”

The frontman says that invasion of privacy was part of the reason he pulled back on using Instagram, that and the so-called “perils of social media”: “I don't use Instagram anymore for anything other than music information and I delete it again as soon as I've put that shit up. It's a scary place.

“I'm not fuckin' Jay-Z, but you do get people you will never know - you don't know and will never know - telling you you're a piece of shit or something like that.”

Ultimately, Tasmania, while bristling with desperation, takes on a hopeful tone – helped by its glam-pop aesthetic. It’s an album that, in touching on difficult issues, is also made for dancing: “There's something nice about having the body part of it being really visceral and physical and dance-y, and the brain part of it being less so.”

Allbrook, in the end, connects that embodiment to a feeling of “optimism and love”: “Part of the whole resignation towards bad things happening is that you've gotta make the best of your time and appreciate things that are physical and tangible. And when real big things are threatened to be taken away from you, like the water and the trees and stuff like that, it's like you want to try to enjoy the music [and] dancing.”

This story was originally published in the March issue of The Music. Pick up a copy of it on the street now.