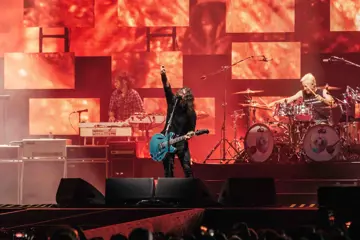

Pussy Riot

Pussy RiotLast week, the Oxford University Press announced that "post-truth" is 2016's word of the year. Thanks to the boorish political grandstanding of the Brexit referendum in the UK and Donald Trump's Presidential campaign in the US, the value of the truth, particularly within political arenas, has been ground into dust. We are living in a golden age for demagogues, where lies and political pandering hold more power and influence than the facts.

Satirists have long been the most incisive lampooners of the politically corrupt, but in an age when the likes of Trump, Nigel Farage and Pauline Hanson earnestly trade in ideology more absurd and extreme than any skit writer would dare invent, humour has become a woefully inadequate medium for taking politicians to task. And besides, is such barefaced and unflinching hate-speak really anything to laugh about?

Theatre-maker Natalia Kaliada, the co-founder of the Belarus Free Theatre, is an artist for whom the truth is non-negotiable. Founded in 2005, the company is the only theatre troupe in Europe classed as an "enemy of the state," blacklisted by Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko. Forced to flee Belarus in 2011, Natalia is now based in London, along with husband Nicolai Khalezin and BFT co-director Vladimir Shcherban. This defiant trio of theatre activists have experienced firsthand the dangers artists face when they attempt to challenge the state with cold hard facts.

"This is how dictatorships work: first they try to imprison your consciousness and when that doesn't work, they imprison your body."

"Belarus has been under a dictatorship for more than 22 years and this was our entrance point into political theatre. It was a way to confront what was happening all around us: our friends were being kidnapped, killed, arrested and tortured," Kaliada explains. "As political refugees living in the UK, we began to understand that we are responsible not only for Belarus, but for the whole geopolitical knot. We felt it was very important to talk about the dictatorship in Russia, as it is a very real threat to the entire world - just look at what is happening in Syria. But we also wanted to connect those geopolitical dots to show that it cannot be left out of a global context. We are sharing what is happening to people in our part of the world, but we don't refer to what's on stage as specifically representing Ukraine, or Russia or Belarus. We want people to understand that this isn't just something happening somewhere far away; it could happen to them right here."

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

The company's latest production, Burning Doors, reveals the stark realities of Russia's authoritarian politics via the experiences of three artist-activists punished by the Putin regime. Ukrainian filmmaker Oleg Stentsov was accused of planning terrorist attacks after speaking out against the Russian annexation of the Crimea. At a Communist-era style show trial, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison. Performance artist Petr Pvlensky, who has used self-mutilation, including sewing his own lips shut, to protest Russia's hardline cultural censorship, was jailed for seven months for setting fire to the doors of the Federal Security Service's HQ in Moscow.

The most high-profile collaborator involved in the production is Maria Alyokhina of balaclava-wearing punk protest band Pussy Riot. Along with two other members of the band, she was sentenced to almost three years in prison in 2012 for "hooliganism" after staging a guerrilla performance in a Russian Orthodox cathedral to challenge the church's support of Putin. News of the incarceration and conviction of the "Pussy Riot three" sparked international uproar, but despite widespread criticism of the disproportionately severe treatment of Alyokhina and her band mates, the Russian judiciary refused to soften its punishment.

"A lot of my friends and even people who I didn't know but who came to support us, who took to the streets and came to the doors of our prisons, were beaten by Russian government officials."

"I don't regret anything," Alyokhina defiantly claims. "I wouldn't do anything differently because I can use those experiences as an artist and I can use that art to reflect the truth." Unlike the unruly, brattish Punk bad boys of the '80s, like the Sex Pistols or The Clash, Pussy Riot is not so much about anarchy as it is about rebellion. "For us, punk is not just music. Punk is a way of life and the opposite to the Russian way of life," Alyokhina maintains. "We had something we wanted to say, and we wanted our words to be as loud as possible."

Since her early release from prison in 2013, after serving just under two years of her sentence, Alyokhina has become something of a political activist celebrity. She's delivered lectures around the world about her experiences and even made a cameo appearance on the hit Netflix drama House Of Cards last year. Undoubtedly, these platforms have allowed her to reach a vast international audience, but she's conscious that her fame should not overshadow her political credibility. "These programs are not the main example of how we are fighting for a better life in Russia, because in the West, if you support Pussy Riot and go to the Russian embassy, it's a nice thing to do. But in Russia, you could literally be beaten for it, and a lot of my friends and even people who I didn't know but who came to support us, who took to the streets and came to the doors of our prisons, were beaten by Russian government officials. For me, that's even more important."

Kaliada readily concedes that the truth is often a much harder thing to accept than the crowd-pleasing post-fact rhetoric that has become so commonplace. "We're talking about the greatest pain in our lives. It's a very complex emotional and mental process. It isn't easy, but we needed to share the depths of these experiences with absolute honesty," she insists. "This is how dictatorships work: first they try to imprison your consciousness and when that doesn't work, they imprison your body. We use our bodies to subvert those systems. When dictatorships put pressure on artists - when artists are put in jail - we become stronger. It is a very emotionally complicated process and all of us have fear; we are human beings. But if we can use our bodies and our consciousness to tell the truth of this story, there is nothing left for them to take."

Belarus Free Theatre presents Burning Doors, at Arts Centre Melbourne 29 Nov — 3 Dec.