MARIANNE & LEONARD: WORDS OF LOVE

Once, Nick Broomfield was infamous as a documentarian. He was shameless. A doorstepper. A muckraker. Where classical documentaries were recorded from an observationist, objective distance, Broomfield was forever walking into frame, boom-mic in hand, making himself the star of the show. It’s been strange to see Broomfield, in recent years, turning sensitive, reflective; his documentary chronicle of Whitney Houston, 2017's Whitney: Can I Be Me?, was striking in its sincerity.

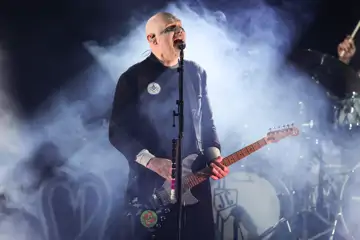

Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love goes beyond this, becoming Broomfield's most openly sentimental movie. Where 'personal', for the filmmaker, once just meant his own provocative presence, here it means something else entirely. It's a film about Leonard Cohen, and at times it submits to the tired format of the regular rockumentary. But, as the co-billing in its title suggests, it’s also about Marianne Ihlen, the woman who inspired the classic send-off So Long, Marianne (freshly covered by Courtney Barnett).

Ihlen was a long-time lover of Cohen’s, but also, it turns out, previously a lover of the young Nick Broomfield. And so, amazingly, we see film that Broomfield shot in 1968, on the Greek Island of Hydra, where he first met Ihlen, who’d been living there for a decade, much of that time alongside Cohen. Looking back on this distant past, some six decades later, it makes sense that this undertaking is filled with melancholy. Ihlen and Cohen are both dead, now, as are so many of the other people Broomfield met; the documentary is as much a study of the many casualties of Hydra’s unchecked bohemian debauchery — and its absent, careless parenting — as it is about Cohen’s career.

Of course, for those coming for that, there’s all the big, expected beats: a writer writing his first song; taken under Judy Collins wing; becoming an unlikely hero; shit-tons of drugs and women (a former manager who fondly recalls pulling tail is pretty gross); performing at the Isle Of Wight in 1970; the making of Death Of A Ladies Man with a gun-crazy, off-the-wall Phil Spector; recording Hallelujah, that unexpected busker anthem; the monastic-exile years; the financial-manager embezzlement; the late-in-life comeback to adoring arenas. There are some amazing isolated moments — Cohen and crew, on a tour bus, singing an a cappella, hollered version of Memories, say — but this stuff feels pro forma in a portrait that’s, otherwise, meant to be far more personal.

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love does effort to get at that feeling, at a kind of intimacy. Broomfield interviews a bunch of friends and family, people who were there with them, especially in the pre-fame ’60s on Hydra. Sometimes, the subjects’ stories can take you into that milieu. Other times, it all just feels like gossip. Much of the talk is about sex, especially with regards to Cohen on tour (there’s plenty of archival footage showing this ‘ladies man’ at work, too). But when there’s too much of that, when this feels like it’s treading close to the biopic's generic depiction of the philandering important-man and the woman he left behind, Broomfield is the one who pulls it back from the usual framing, talks about what Ihlen was doing with her life, giving the unglamorous, and unfamous, something nearing equal footing.

When Cohen is shown on stage, playing So Long, Marianne at the Isle Of Wight, we don't sit with this ‘classic’ performance of this classic song. Instead, as we watch Cohen on stage, the song is bumped down, and overlaid is Ihlen talking, unflatteringly, about the couple’s decaying relationship, how dark and bad things got; this juxtaposition trampling on classic-rock clichés, the myth of the Great Male Artist's great performance.

It becomes clearer, on close, why Broomfield did this: instead, he wants to show a different live version of the same song. The film climaxes with Cohen on stage, in Oslo, at the very last show where Ihlen saw him play before her 2016 death. She’s in the front row, singing along to this song written about her. Performer and ‘muse’ are connected in that moment, and, still, after their respective deaths, forevermore in song. This is the profundity Broomfield, wearing his heart on his sleeve, is out to get at. Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love is, suiting its title, a film made with love, about love. It's, as a piece of cinema, essentially 'ok'. But you can't doubt its sincerity.

★★1/2

CHILDREN OF THE SEA

Ayumu Watanabe’s eye-popping animé is an eco-mystical fable, using poetic evocations of connections between the skies and the seas to plunge into an underwater world of wild, psychedelic, luminous visions. “This is the story of the seeds of stars, the children of stars, and the birth of stars, from the stars,” says an opening title card. If that sounds confusing, well, Daisuke Igarashi’s narrative — adapting the screenplay from his own manga — doesn’t do much to clear it up.

The first image in Children Of The Sea is a POV childhood memory, a young girl’s eyelids opening to the electric-blue wonders of an aquarium. In the narrative present, she’s adolescent Ruka, who finds her summer-break — a whole otherworldly adventure flourishing when freed from the strictures of schooling — upended upon a visit to the aquarium. There, she meets a pair of boys, Umi and Sora, who are the titular offspring; mysterious, quasi-mystical figures that were, apparently, “raised by dugongs” in their early years (the literal translation of the manga is ‘Marine Mammal Children’). Now, they’re forced to spend some of their lives ashore, where they’re monitored by a crew of marine researchers. And many of the concerned men looking after them, or following them from a distance, are sure these boys connected to a host of unexplained oceanic/astronomical phenomenon.

The fact that there are scientists saying sciencey-sounding things — the film feels, in some ways, like a valentine to marine biology — doesn’t distract from the fact that Children Of The Sea is full of bonkers mysticism and splendid psychedelic visions of imagined underwater/interstellar realms. Whilst there’s little realism in the marine-creatures-meeting-up-for-a-celebration story, there’s that great, familiar animé quality of lovingly depicting seasons, weather, insects, trains, meal preparations; the details, as always, mattering so much. This makes for visual contrast that serves Children Of The Sea well: there are images to marvel over in domestic, oceanic, and psychedelic settings.

★★★1/2